Two weeks before leaving office, the Trump administration is planning to hold the first-ever oil and gas lease sale in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

The sale, scheduled for 10 a.m. Wednesday in Alaska, is a controversial milestone in a 40-year battle over whether to drill for oil in a part of the refuge called the coastal plain.

So, how did we get here after such a long debate? And what will happen next?

Here’s what we know so far.

What, exactly, is the coastal plain?

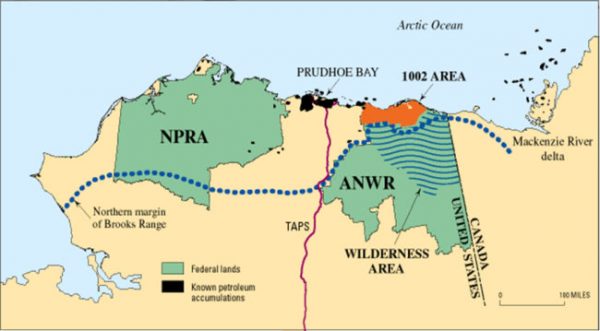

The coastal plain, also known as the 1002 Area, is the northernmost slice of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, along the Beaufort Sea.

It covers an area roughly the size of Delaware, and makes up about 8% of the refuge, in northeast Alaska.

There’s one village within the coastal plain, Kaktovik, where Inupiaq political leaders support drilling even as residents are divided on the issue. The land is also home to migrating caribou, birds, polar bears and lots of other wildlife. And, it’s thought to sit on top of, potentially, billions of barrels of oil.

For decades, conservation groups and Gwich’in tribes who live just outside the refuge have fought to protect the coastal plain from oil development, while many Alaska politicians have fought to open the area to drilling.

After so much debate, how did the government get to a lease sale?

Part of that story starts in 1980.

That’s when Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. The act created the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Before that, it was the smaller Arctic National Wildlife Range.

The act designated millions of acres of the refuge as wilderness, but not the coastal plain. Instead, in Section 1002 of the act, Congress asked the Interior Department to study the possibility of oil development in the coastal plain. (And it subsequently became also known as the 1002 Area.) Congress also reserved the power to decide later whether to open it to drilling.

And so began the fight over what to do with the land, which went unresolved for decades.

And then came 2017.

What big change happened in 2017?

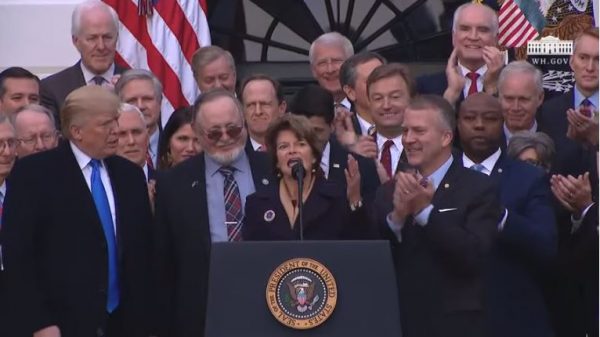

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Republican U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski worked with the White House to open the coastal plain to drilling as part of the massive tax bill. It was pushed into the bill as a way to create revenue to offset tax cuts.

The bill directed the federal government to carry out two lease sales in the coastal plain by the end of 2024, with the first by the end of this year.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the leasing program could generate $1.8 billion over a decade, to be split between Alaska and the federal government.

But critics of the sale, including the watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense, say they expect the dollar-figure to be much lower.

Since Trump signed the tax bill into law, the federal Bureau of Land Management has led the environmental review process that’s required before a lease sale can take place.

Opponents of the sale say the administration picked up a lot of speed — too much speed, they argue — to lock in oil drilling in the weeks after the November presidential election. BLM set Jan. 6 as the date for a lease sale in early December, while a 30-day comment window was still ongoing.

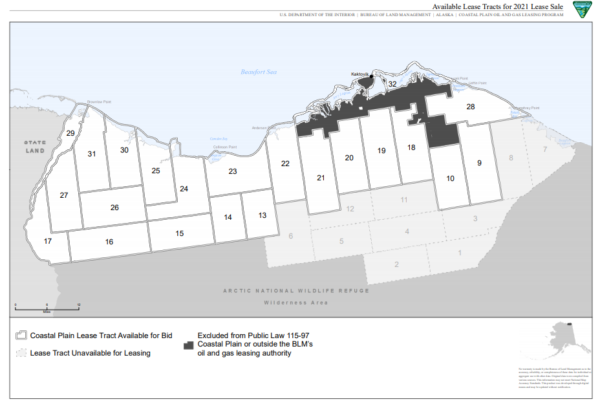

What is the Trump administration selling exactly?

It’s offering drilling rights to 22 tracts of land that cover about 1 million federal acres of the coastal plain, or about 5% of the whole refuge.

The highest bidder on each tract will get a 10-year oil and gas lease for that piece of land. If a tract gets no bids, then no one gets the lease.

What happens Wednesday?

Those interested in buying the oil leases had to submit sealed bids to the government last month.

At 10 a.m. Wednesday in Alaska, government officials will open those bids in an event streamed online, and accept the highest offers.

What happens after the sale?

The leases will not be issued on Wednesday.

The Department of Justice will need to conduct an antitrust review. And winning bidders also must sign paperwork and pay.

The process to issue the leases usually takes about two months, but the Trump administration will likely try to finalize the sales in just two weeks, before Democratic President Joe Biden is sworn in Jan. 20.

Wait. Aren’t there a lot of lawsuits?

Right. Looming over the sale are four lawsuits, filed by environmental organizations, the Gwich’in Steering Committee, tribal groups and a coalition of 15 states.

In court documents, they argue the Trump administration’s oil-leasing program for the refuge is rushed and legally flawed, and any agreements based on it — including any leases — should, basically, be canceled.

In three of the lawsuits, the groups requested a preliminary injunction.

That means they wanted U.S. District Court Judge Sharon Gleason to stop the government from issuing any oil leases for the refuge, and from allowing any seismic oil exploration, until the broader lawsuits are resolved.

But Gleason denied those requests late Tuesday afternoon.

What do we know about who will bid on the oil and gas leases?

Not a whole lot.

BLM spokeswoman Lesli Ellis-Wouters said Monday that the agency has received bids, but she declined to say how many or who they came from.

Oil and gas companies aren’t talking publicly about their plans for the sale either.

A spokesman for the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, which seemed like a likely contender to participate in the sale, confirmed by email Tuesday that it is not bidding.

Oil industry analysts have said they expect interest to be lukewarm in the sale for many reasons.

A major one is the opposition.

Opponents to drilling in the refuge have raised concerns about its impacts on Indigenous people, the global climate, and wildlife, including the caribou that give birth in the coastal plain and the polar bears that den there.

They’ve lobbied oil companies, banks and other financial institutions to stay away from developing the refuge. A number of major banks say they won’t fund oil projects in the Arctic.

Also, drilling in the Arctic is expensive, and last year’s oil price war, paired with the pandemic, hit the industry hard.

On top of that, there’s uncertainty around future oil demand, how much oil actually exists under the coastal plain and the changing presidential administration.

Citing concerns about limited industry interest, Alaska politicians have recently lobbied for the state to step into the sale.

And, in a very unusual move, the board of the state-owned Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority voted to bid up to $20 million on the leases.

An AIDEA spokeswoman declined to say this week whether the corporation actually decided to submit any offers.

Who can bid on the leases?

The federal rules are kind of vague, and say those who can hold a lease include pretty much any private, public or municipal corporation organized under the law.

Ellis-Wouters, with BLM, says bidders must have an intent to develop the land.

Who supports drilling in the refuge and who opposes it?

It’s a complicated answer.

Alaskans are divided on the issue, just like the country is.

Many Alaska politicians, including the current Congressional delegation, have long fought to open the coastal plain to drilling. Oil and gas industry trade groups also support developing the coastal plain, along with the Kaktovik Iñupiat Corporation, the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation and Alaska’s governor. They argue it’d be good for jobs, the economy and state revenue, and say drilling can happen without harming the land and animals.

On the other side, environmental and conservation groups have long tried to keep oil rigs out of the refuge. They counter that there’s no way oil development can happen in the coastal plain without harming wildlife and the tundra, and without exacerbating climate change in a place that’s already warming fast. Among some of the most vocal opponents are the Gwich’in, an Indigenous group who say the land is sacred and whose members hunt caribou that commonly give birth in the refuge.

President-elect Joe Biden says he also opposes drilling in the refuge, but can he reverse oil leasing?

If the oil leases are finalized before Biden takes office, it could be more difficult to reverse course.

It’s possible Biden could try to buy the leases back.

Also, just because a company has a lease doesn’t mean it can immediately go develop the land. Analysts have said it’s possible a Biden administration could hold up the process for companies to get the permits they need to search for oil and build their infrastructure.

“What they would try to do is make it so difficult, so onerous, to get the array of permits that the companies just kind of say, ‘Well, we’re not going to spend 10 years just trying to get a simple permit, we’re going to put our money and our investment elsewhere,’” says Andy Mack, a former Alaska natural resources commissioner.

Meanwhile, in federal court, the lawsuits are expected to continue to wind through the system, and a judge could later rule to cancel the leases.

Still, the 2017 tax law exists, ordering a second lease sale in the coastal plain by the end of 2024. Congress would have to pass a law to undo that part of the tax act if it doesn’t want to follow through.

What questions do you have that we missed? Email reporter Tegan Hanlon at thanlon@alaskapublic.org.

Alaska Public Media’s Nat Herz contributed to this report.

Editor’s note: This post has been updated.