Supporters of drilling in the northernmost slice of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge often point to its oil potential as a reason to develop the remote stretch of land.

But what does the federal government actually know about how much oil sits under the refuge’s coastal plain, which will be put up for sale on Jan. 6?

While geologists say the rock formations, oil seeps and old seismic results seem promising, big questions remain about where the oil is trapped, and exactly how much of it there is.

“We don’t know very much about this area,” said David Houseknecht, senior research geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey and expert on the coastal plain.

“There are a lot of uncertainties that are difficult to quantify in the absence of better quality data,” he said.

What the government does know about the amount of oil in the coastal plain dates back decades.

In 1998, the USGS calculated there’s anywhere from 4 to 12 billion barrels of recoverable oil under the federal lands, which cover an area roughly the size of Delaware.

That’s a whole lot of oil, said Houseknecht, but also — a wide range.

“That range is so big because there’s been no wells drilled on federal land and because the seismic data is pretty old and low resolution and erratic,” he said.

Companies use seismic technology to map underground rock formations, and hunt for oil. The seismic data for the coastal plain is from the mid-1980s.

Technology has come a long way since then, Houseknecht said.

“Going into a lease sale in the coastal plain, with the only data being 35-year-old, 2-D data is quite unusual,” he said.

An Alaska Native village corporation is trying to get approval to conduct 3-D seismic exploration, using massive trucks that roll over the tundra and vibrate the ground. Conservation groups argue the work will cause too much harm, including to the tundra and to polar bears that den there.

Another key piece missing from the USGS assessment is any data from actual wells drilled in the coastal plain in search of oil, Houseknecht said.

That’s because there’s just one, drilled back in the 1980s, on Alaska Native land. And the results are a closely-guarded secret.

“I signed a confidentiality agreement, and it didn’t have an end date on it,” said Mark Myers, a geologist and former commissioner of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources.

Myers is one of the few people who have seen the results from the test well, outside of the big oil companies that paid for it.

“I can’t comment on it, in terms of what I saw,” he said. “Even though it was a lot of years ago.”

A New York Times investigation based on legal documents suggested the results were not promising.

But Houseknecht said companies with that well data still have critical knowledge.

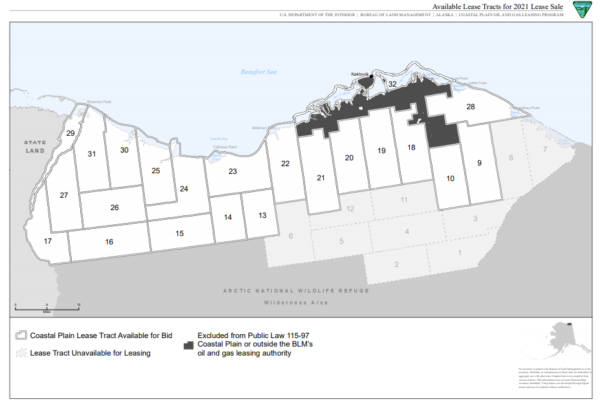

USGS interpreted the old seismic data to show most of the oil is likely in the western part of the coastal plain and said the other side didn’t appear to have the right conditions to hold a lot of petroleum.

Houseknecht said those companies with the well results, however, would know a lot more about the rocks underground on the eastern side of the refuge, and their potential.

“Whether that source rock is present or absent, whether that reservoir rock is present or absent, is huge,” he said.

Houseknecht said more is not known about the oil potential of the coastal plain because it wasn’t until late 2017 that Congress decided to open the land to drilling, after decades of protections.

An application in 2018 for new seismic work stalled.

The USGS also had the 1980s seismic data commercially reprocessed a couple years ago, Houseknecht said, which resulted “in a much better resolution than we do internally.”

The agency had planned to conduct a new oil assessment using the reprocessed data, he said, but after the 2017 tax act was passed, the Interior Department called off the work.

Houseknecht said the department did not give a reason why.

Myers, the former commissioner, said even without updated seismic data, he thinks one big selling point for oil companies is the fact that the coastal plain is onshore, making it cheaper to access than offshore prospects.

And, he said, there just aren’t a lot of opportunities for companies to get in early on a potentially massive oil find.

“I would say ANWR falls in that high risk, high potential — not high risk of oil, but high risk of execution,” he said. “When you put it all together, will that attract somebody? I think it will.”

When Myers says high-risk of execution, he means there’s opposition that could derail a company’s project.

Critics of drilling in the refuge say the land should be protected, and they’ve raised concerns about oil development’s effects on ecosystems and the global climate. The coastal plain is home to polar bears, migrating caribou and other wildlife.

Conservation and some tribal groups have already filed several lawsuits that aim to stop the lease sale.

While oil potential will likely be the first thing companies weigh when deciding whether to bid in the sale, Myers said, they’ll also take into account a string of other factors, including the lawsuits, costs and the changing administration.

President-elect Joe Biden has said he opposes drilling in the Arctic refuge.