Transcript

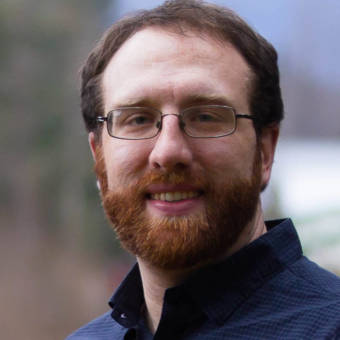

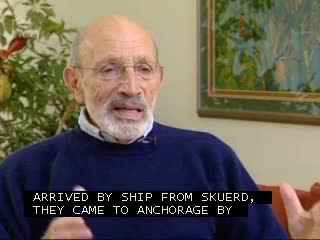

Vic Fischer: When I came to Alaska in 1950 I was completely shocked to find that I was no longer a full-fledged citizen of the United States. I had fought war to save democracy. I had already voted for President and US Senate in Wisconsin before and came and all of a sudden I’m in Alaska. I’m deprived of right to vote for President, right to have voting representation in the US Congress, the old cry of taxation without representation. And I was in this federal enclave of colony of the United States Government. And so I was outraged and there were quite a few other young people, veterans mostly, who were coming to Alaska at that time and we all felt very dissatisfied with the situation.

Opening Titles

Narrator: Alaska experienced major growth and change in the 1940s and 1950s, fueled largely by the territory’s militarization during World War II and the onset of the Cold War. Territorial status left many of the of new residents, like Vic Fischer, indignant. A diverse and growing number of Alaskans, from career politicians and bureaucrats to shopkeepers and missionaries in the bush, joined the statehood movement that culminated in 1959. Fifty-five delegates from across the territory met in Fairbanks during a frigid winter in 1955. They wrote a state constitution from scratch and charted a course to turn Alaska into the 49th state.

In this episode, eight key figures from state history will describe how it all came together. In later episodes, they’ll share personal stories and talk individually about how their lives intersected with history.

Intertitle: Before Statehood

Vic Fischer: We had a number of congressional hearings on statehood committees would come up to Alaska aside from committee hearings in Washington …

Those hearings were fascinating. I remember Mildred Kirkpatrick testified at that particular hearing also, which was held in the Carpenter’s Hall at Fourth Avenue and Denali. And she was the Republican National Committeewoman and she told about the – working and being enthusiastic about the Republican President being elected Eisenhower becoming President and how she received a formal invitation to the inauguration and she was excited and she got on a plane and flew down to Seattle to go to Washington, DC. And in Seattle she had to go through immigration just as if she were coming from Japan or France, she had to go through immigration to prove that she was an American citizen. And she broke down with the ignominity of the situation that my president was being inaugurated and I’m treated like a foreign and not an American citizen.

Vic Fischer: The territory had very limited authority. The governor of Alaska under the territorial government was appointed by the President. The highway department was run by the federal government. The court system was run by the federal government. The communications system, long distance telephone system, was run by the Army. Essentially everything all around. Management of resources, fish and game, lands, forest, everything was federal.

Vic Fischer: And the main argument that I advanced then was that with statehood we could control over resources, control over transportation, control over other aspects of the infrastructure and that we would be able to manage our own affairs and move things forward rather than depending on decisions made in Washington by people who really didn’t care about what happens in Alaska.

Vic Fischer: Late 1954, it became very clear that congress again hadn’t acted on Alaska statehood bill and that something more needed to be done, some kind of a push was needed and Wendell Kay and others suggested that well the time has come to go ahead and write a constitution for the future state of Alaska. Hawaii had already adopted a constitution in 1950.

Tom Stewart: As a territory if we wanted some official expression to the President or the Congress we had to write a memorial asking them to do something and it isn’t very long – maybe I should read it. It is House Joint Memorial Number 1 passed by the House January 25, 1955 and by the Senate February 8th. It is addressed to the Honorable Dwight D. Eisenhower, President of the United States who was not especially in favor of statement and to the Congress of the United States.

In memorial of the legislature of the Territory of Alaska in 22nd Session assembled respectfully submits that:

We representatives of the citizens of Alaska again appeal to you the duly constituted representatives of all the people of the United States that you may recognize us and our constituency as equal citizens under the democratic flag of America. We remind you again that the people of Alaska have demonstrated with all their history their territorial status, their inherence to the principles upon which the government of the United States was founded and remind you by referendum and by acclamation through our land an overwhelming majority of our people have declared unequivocally their desire for statement and the right of a free people to govern themselves. We recall to you that your own electors through the platforms of the major political parties and by their popular accord have given you a mandate for statement for Alaska and therefore we ask that you collectively and as individuals dismiss all partisan concerns, look only to the merits of our cause, recognizing correctly injustice we suffer in not being allowed to govern ourselves or participate in the election of the President or having voting representation in the Congress, all of which may be cured by enabling immediate statehood for Alaska your memorialists ever pray.

I wrote that – that’s the way I felt at the time.

George Rogers: Tom is the one who sort of went into local and territorial politics in order to promote statehood and he did it very systematically and very thorough and he worked very hard on this. He worked up the idea of the convention. He also worked up the idea on staffing it and bringing in a consulting firm that was top flight to tell us. He was determined to have what he considered to be a model constitution. We could learn from what mistakes had been made in the past. So he had devoted a lot of his time to that. When he was in the legislature he worked very hard to get the legislation for the convention, the appropriations, all those sort of things. And it was almost a single-handed job.

Tom Stewart: And we decided on a convention of 55 members because that would give us an opportunity to have better spread. Forty-eight of those members were elected from those 22 – from those districts, but there was one district at large. So seven of the members ran at large over the whole territory. They were people like Ralph Rivers and his brother Vic Rivers, who were well known. Ralph had been the Attorney General elected territorial wide and Vic had been the President of the Senate. And there were four or five others that ran at large, but the net result was that the convention was the most representative body that had ever been assembled in a governmental function in Alaska. We had people from Ketchikan, Wrangell, Petersburg, Juneau, Haines, Valdez, Cordova, Kodiak, Seward, Dillingham, Palmer, Unalakleet, Nome, Kotzebue, far and away – the most representative group that had ever assembled for a governmental purpose. Today you couldn’t do that because the Supreme Court decision in Baker vs. Carr determined that for an election to state legislatures one man – one vote. The districts have to have drawing of equal populations within a small percentage and it would not be possible to have that kind of a body assembled, but at that time it was and that was a critical function – a critical aspect of the success of the convention because the people at large knew that they had representatives participating in the decisions that were made there.

George Rogers: Not everybody at the convention was in favor of Alaska becoming a state but they went along with this idea because it was an opportunity to examine what was possible here and I got some very interesting feedback from some very conservative people on that. That was what that whole experience was just marvelous.

Intertitle: Choosing Where to Convene

Tom Stewart: And I was elected to be the secretary of the convention so I resigned as executive officer of the statehood committee and served as the secretary of the convention in charge of all the administrative aspects – getting these consultants to come, arranging their travel, arranging all the physical space, all the details and structure of that convention.

Tom Stewart: And everywhere I went I said how do you set up a convention? How do you get qualified advisors to help you work on the substance of a constitution? And I got some excellent advice from Mrs. Katzenbach, …

…who was a Vice President of the New Jersey Convention of ’46, which was a very successful convention.

…She said hold your convention at the State University. I said we don’t have a State University. We have something called the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines. Well hold it there instead of in the capitol. Because the capitol has entrenched lobbying interests and they will be lobbying for their pet projects. If you go to the University you will have a library facility. It is a much better scene. …

Katie Hurley: Commons, it was the Commons. It was a very new building. And the bookstore was there and they just gave the bottom part over to the delegates. And they had made a stage so that Bill Egan was one level above, but he was the only person up on that level and I was right below him. I have a picture. It is very primitive. It is not fancy. It is just this table and everybody smoked who smoked. Can you believe it? You can see everybody smoking during the session. Bill Egan was a chain smoker and I never smoked, but I certainly breathed enough smoke during that convention.

Tom Stewart: It was an unpopular decision in Juneau because there were a lot of people in Juneau who were concerned even in those days about the possibility of moving the capitol. And I remember going to a Chamber of Commerce luncheon and Curtis Shattuck, whom I already described to you, was an anti-Gruening Democrat, sitting across the table from me . Underneath the table he kicked me severely in the shins because I had promoted the idea of having the convention at the University.

Jack Coghill: The thing is that Juneau, and of course there was big push by a lot of the heavies in Anchorage to move the legislature to move the capitol and all of that was a part of it, so Juneau and southeast Alaska didn’t want anything to do with Anchorage. And so Fairbanks, we became the neutral ground. And so the Fairbanks delegation, the Nome delegation, and the Southeastern Delegation ganged up on them and said we’re going to have the Constitutional Convention in Fairbanks.

Jack Coghill: And so you didn’t have organized groups. You didn’t pressure groups coming out there to the University and sitting. And a lot of times a lot of school groups were out. I had school people from Nenana come up and we had one of the gals that was a senior that gave a talk to the Constitutional Convention. We had a lot of visiting firemen that spoke to us and one thing or another, but pretty much left us alone to do the things that we had to do.

Tom Stewart: The only organized group that came and lobbied the convention. …

The education lobby. The school superintendents came to represent their representatives to Fairbanks and they had a three-page detailed article on education.

The constitution says about education there are three sentences. The legislature shall by general law establish and maintain a system of public schools open to all children of the state and may provide for other public educational institutions. Schools and institutions so established shall be free from sectarian control. No money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.

That’s the whole constitution on education. Fundamental basic concept. The details are left to the legislature.

Jack Coghill:

In fact the ordinance that we put in abolishing fish traps. We didn’t get the fishing industry out of Seattle or the pressure groups from the fishing industry that were Nick (inaudible) and all of those that were the big fishmongers. They didn’t show up because nobody thought we were serious. Thought we were just a group of people going through an exercise.

Tom Stewart: It was the remoteness, the middle of the winter. It was a cold winter – 50 below zero.

George Rogers: When I first saw the University it looked like a Siberian penal institution. We had these wooden structures with a water tower which had a clarion was tape playing up on top there and just reminded me of pictures I’ve seen in Siberia of these buildings. And this was this territorial days so they couldn’t go into debt.

Vic Fischer: I remember the first day I tried to move the car and the car didn’t want to go. And then I forced the car forward and it sort of went ga-plunk and I got out and looked and couldn’t see anything and didn’t have a flat. Then I went and pushed it again and it went ga-plunk and then looked out. Anyway, then I learned that tires froze flat at least in those days. I’m not sure they still do. But it was quite an experience to be in this cold Fairbanks all of a sudden. And that of course was a continuing theme through the convention.

Intertitle: Electing a Convention President

Vic Fischer: The most active one in pursuit of the presidency was Vic Rivers of Anchorage. He had been a territorial senator, very strong politician and engineer by profession. A very, if you look around you’d identify him as a powerful politician. And he was lobbying actively to be selected for that post. Many of us novices, younger ones, who had not been involved in politics were suspicious of anyone of that sort who was actively lobbying for the position you might say wanted it.

Vic Fischer: Our concern basically was that some of those older establishment types were going to control the convention and try and push the constitution in some direction that we didn’t know but that there might be some hidden agendas

Vic Fischer: And on Sunday morning, the day before the opening of the convention, Egan arrived having hitchhiked on a truck from Valdez and he was confronted with the proposition and he was agreeable and Burke Riley was one of those who was very strong advocate for Bill Egan. And so then there was sort of an agreement among this group of younger rural types, the nonpolitical types that Bill Egan ought to be president, but no one was skilled enough to make a count really and know for sure.

George Sundborg: I didn’t vote for Bill Egan, which I should have done. Bill Egan proved to be a wonderful presiding officer. He was so thoughtful of everybody there and all of his decisions were right and I was so impressed with him. But even though I hadn’t supported him for president, he appointed me chairman of the committee on style and drafting. And I’m sure it was because I’ve had a journalistic background and could put words together.

Katie Hurley: He didn’t care about being a star himself I guess is the best – the reason why he – and he was so willing to look at people individually and not be judgmental. And yet you know there were people who he had worked with and I think were on opposite sides but he saw his role, just did it, and much more – much better than anyone could have imagined that he had a very you know just a gentle way.

Maynard Londborg: You hear from ex-delegates now they’ll all – that’s about the first thing they mention is how fair Egan was as a chairman, president of the – there was a lot of us that didn’t know the fancy Roberts Rules backwards and forwards and he could cut us off and just you are out of order you know and you’d stand there bewildered. But he would just like a good schoolteacher he would just draw it out.

Katie Hurley: My favorite is when he would stop – he’d see somebody who was inexperienced, hadn’t been in a legislative body or hadn’t served on a city council or had any kind of experience and he could tell that they wanted to make a motion or make an amendment and he’d stop and call a recess and motion to them to come up and he’d say yeah. Cause I could hear him cause he was – they were right beside me and he’d say did you want to have – say something or did you want to make a motion. And he’d help them write it and that’s a real gift in a presiding officer. And of course it was informal enough that you could do that too.

Vic Fischer:

It was as democratic with a small “d” as it could be. It was totally without partisanship and Bill Egan insisted on that. That was the agreement of the convention, but Egan insisted on it. A couple of times when a delegate would refer to something political, Egan would just cut the delegate off. And so Egan made sure that the convention worked as a group, that everyone marched together and votes were of course taken where divisions occurred on specific issues, but it was own man issues. It was never in personalities, it was never on partisan politics.

George Rogers: He had this phenomenal memory. He would meet you in a crowd and come back 10 years later and say he remembered oh you had kids and how is so and so doing. He could remember these details. He didn’t have somebody prompting him. He was just incredible. When he was governor he would dress up like Santa Claus and go down to the supermarket and greet everybody. Things like this. He was the common man. He had a lot of good common sense and on the whole he was very trustworthy. He was just right for the job. He had his shortcomings too. We all do, but they weren’t – he was not corrupt in any way, just a – that to me is the bottom line with this guy. Real, this guy is honest, and he is ethical and he met all those things.

Intertitle: Committees and Consultants

Jack Coghill:

I think we went from November until the 20th of December or something like that and then we took a three week break and we came back in January and we finished up in February.

Maynard Londborg: I went there and had some good advice from a fellow that was running the trading post. He said well, be sure you pick up a good copy of Roberts Rules of Order. And he said another thing I think you will find most of the work done in the committee, in the various committees. So it’s real important that you get on the right one and that is where the work is done. Otherwise it is brought into the session as a whole and first reading, second reading and final reading.

George Sundborg: The committees that were set up were a committee on the legislature, committee on executive, committee on the judiciary, committee on public lands and so on.

Tom Stewart: Virtually all the committees got expert academic people to come and consult with them for a week or two or three as the case may be.

George Sundborg: They all met as committees for several months and drew up an article for that part of the constitution. And they would bring it before the plenary session when it was finished.

Katie Hurley: I was the Chief Clerk. And that meant that I was the person who took the minutes of the plenary sessions. Plenary I guess everybody knows that that is when everyone was together and all 55 delegates were there. …

And I had – I was in charge was what they call the boiler room which was where the stenographers and typists took care of committee reports and so forth, but we had a very small staff I think of about six people.

George Sundborg: And we would discuss it upstairs and downstairs and all around and finally pass it. And we – after we had passed all of the articles. I think there are 12 of them of the constitution, they turned the whole thing over to the committee on style and drafting.

Jack Coghill:

The only reason why we got through the constitution and we made the constitution as brief as we possibly could, that was part of the – Bill Egan’s thrust with his committee chairmen was keep everything simple. Don’t get legislative intent into the middle of the constitutional structure. And of course that followed through and so we actually in my estimation and a lot of other people that this is out still the best state constitution in the 50 states.

George Sundborg: The fault of many state constitutions, and they have suffered from this, is that they have locked into place provisions that the people have never been able to change. They say in states – a state constitution is of the quality it is quite as much as from it is left out as for what is left in. And it should be just a basic document for the formation of a state so that the state can change its provisions without having to get a two-thirds vote of the people and so on, as is required in most constitutions to get through an amendment. And so we kept away from all of those traps and it is really just a really great basic document.

Jack Coghill:

Territorial law, state law, and the things that you got done or amended are molded or twisted to accommodate contemporary time. Constitutional law is something that should be short, sweet, and direct.

Intertitle: Closing the Convention

Katie Hurley: They were long days at the end.

And I had an apartment in Northward Building and they provided me a typewriter there because there was only one bus a day out and one bus a day back and I didn’t have a car and we all rode out most – a lot of people didn’t have cars. So I would bring my notes back that I wasn’t able to do while we were still at the University back to my room and type away. And sometimes until four o’clock in the morning towards the end, but I was always up and ready to go at eight o’clock.

George Sundborg: I remember one weekend when our committee met practically night and day to finish up some – on some of the articles of the constitution.

Jack Coghill: We had good debate, but see when the constitution when we had a lot of votes that were split but when we finished the document and the Style and Drafting Committee, which was headed by George Sundborg, when they got done putting it all together everybody, all 55 of us, signed the document.

Maynard Londborg: Oh I learned a lot of things while I was up there and that is that you can debate. You can passionately debate but it doesn’t have to ruin a friendship and it is kind of interesting we started talking about missionary work and that but how many churches do not know how to do that. I mean they’ll end up in a bitter fight or something like that, but I learned a lesson there. There were two delegates who were just passionately debating on each side of an issue. And this went on for a long time, long speeches and they were debating back and forth and I had something that I wanted to inject and I thought well if I can go to this one fellow and get on his side then you know he might be on my side because he is against that other fellow. And we had a little recess and I went out in the coffee shop and here the two guys were talking about their next hunting trip they were going to take together. And I thought boy oh, you don’t take anything for granted on the way they debated you know.

Jack Coghill: The thing that I remember the most about the Constitutional Convention was the camaraderie that happened after we decided that the document was the best we could do.

Jack Coghill: And when we got done arguing there was no minority reports, no majority reports, except what was done by the committees. …

George Sundborg: We finally succeeded and signed the constitution in February of 1956.

And it was quite unified. It was like something that had been written by Thomas Jefferson you know?

The leader of the consultant was a man named John Bebout – B-E-B-O-U-T and he was on the staff of the state governors. They have a governor’s council or something that works for all the states and he was great. He made a statement that the Alaska Constitution is by far the best of all state constitutions.

Jack Coghill: When we signed the constitution in Signers Hall it was not the elaborate structure it is now. We had to kick the basketballs out of the way in order to put the seats in for the general public to come and watch us sign the document. …

It was the University gym.

Tom Stewart: And when it came time to sign it, over a 100 copies made, identical copies. There were 55 delegates and each of the delegates wanted to take a copy home with them, but there were five copies that were intended for the President, the senate, the house, the Governor’s office, and archives.

And so I lined 60 signature pages on long tables in the planuria – in the hall where they held the plenary sessions. And the delegates lined up alphabetically and walked down the line and signed their names 60 times, actually 61 times because the paper that it was printed on was a very high quality paper, but they wanted a copy done in calligraphy on sheepskin parchment. So we had this signature sheet for that copy as well. And signed their names 60 times.

George Sundborg: It was very special. And I think everybody who had served as a delegate was emotionally moved by it. We were all crying you know as we went up to sign the constitution. It was a great victory.

Jack Coghill: Now one fellow got a little bit upset. He was from southeastern Alaska.

Robertson. And he went home, but he did sign the document afterwards when they got down to Juneau why they got – Tom Stewart and the guys got him to relent and to sign the document – the constitution. So different than the United States constitution, which had 55 delegates, only 30 what – 38 of them signed the United States constitution. So there was a lot of dissenters.

Katie Hurley: After that They went back over to close the thing, sine die, you know, and that when I called the roll the last time I got so choked up saying their names that when I looked up there are these guys that I never would think that they had tears in their eyes, the ones that were sitting like Steve McCutcheon and Herb Hilscher. I mean those are hard-nosed guys and I had – oh, it was – it’s on the tape, the official tape and somebody sent me that from I couldn’t believe how choked up I was.

Maynard Londborg: Nobody seemed to want to leave after it was all you know the final gavel went down they just – there had been built up such a close friendship among the delegates.

Katie Hurley: It was so emotional at the end.

Because it was like we had been through – I mean starting out with 55 different individuals who had such – so many of them such wide backgrounds and that they could – they did come together so well.

I felt that I had witnessed statesmanship that I’ve never seen since.

Intertitle: The Alaska Tennessee Plan

George Rogers: The statehood proponents were looking at the history of how other states came in. Tennessee, what they did – they didn’t wait for Congress to act. They wrote a constitution. They elected their delegation to congress, sent the delegation to Washington, DC and demanded that they be seated.

George Sundborg: This man named George Lehleitner from New Orleans he had the idea and he got it first when he was a Naval officer stationed in Hawaii.

Tom Stewart: And he had gotten to know Joe Farrington, who was the delegate to Congress from Hawaii as Bartlett was from Alaska and become friends with him.

Tom Stewart: He knew that Hawaii was aspiring for statehood. He didn’t know anything about Alaska.

Tom Stewart: He got the legislative reference service of the Library of Congress to research the history of the admission of states and he found that the last seven territories on the way to becoming a state each of them had elected a provisional delegation to the Congress – two senators and a representative to go to Washington sponsored by the territorial government to lobby for statehood.

He recognized that the process by which legislation gets enacted is – especially in the senate but also in the house is one in which somebody has something they want to do and they contact other members who are their friends and say now if you’ll vote for this proposal for me, you can be sure that I’ll support what you want. And that’s he envisioned these people would do. And he tried to persuade the Hawaiians when they wrote their constitution their convention of 1950 to elect a provisional delegation, then send them to Washington. They could call in every senator and every house member and say I am the duly elected provisional senator or house member from my territory and if you vote for statehood for us, you can be sure that I’ll be back here as a full-fledged member and I’ll support your cause. Vote trading. He tried to persuade the Hawaiians and they determined not to do it.

He never had anything to do with Alaska, but he heard that Alaska was going to have a constitutional convention.

He got acquainted with Bob Bartlett and he said to Bartlett I’d like to go to Alaska and try to persuade the Alaskans to do that. And so Bartlett gave him an introduction. He gave him an introduction to me in Juneau and I had – I collected all the people that were running to be delegates to the convention in this room.

Tom Stewart:

So when the convention sent questions to the people to be voted on there were three questions. The first one was shall the constitution as drafted by the convention be adopted? The second one was called the Alaska Tennessee Plan because Tennessee was the first territory to use this device and shall we elect provisional senators and a house member and send them to Washington as official lobbyists of the Territory of Alaska? Number three shall fish traps be abolished? Because the fishermen involved in the convention, a fellow from Petersburg particularly by the name of Elder Lee, who was desperate that – to get rid of fish traps because the fish traps had been mismanaged and were seriously damaging the fishery.

Those three propositions went to the voters in April of ’56 and I don’t remember it was something like 65 to 35 the vote in favor of each of them. And then there was an election.

Jack Coghill: We got Ernie Gruening and Bill Egan were our Tennessee senators and Ralph Rivers was our Tennessee representative. We sent them back to Washington with the explicit instructions to go demand a seat on the floor.

Tom Stewart: It was a mandate to the legislature of ’57 to appropriate the money to send them. So they did and about April those three went to Washington and set up shop and did exactly what Lehleitner contemplated.

Jack Coghill: And they went around and they lobbied and they took material to every legislator, every senator and every staff person, every house member. And they lobbied the statehood thing.

Tom Stewart: They called on all the senators, some of them more than once and all the house members and said you give us statehood and you can be sure that I’ll vote for what you want.

Intertitle: Statehood Opponents

Tom Stewart: In territorial days the major resources were indeed controlled by nonresidents. Salmon industry, canned salmon because the salmon was marketed by being canned. It was before the days of the freezer ships and sending fresh frozen materials out.

And the same with the mining industry. The mining industry if it is going to be large it requires a lot of capital and the capital basically was not very much available to Alaskans, still isn’t today. You have to go outside the state to get big money by and large.

There were more people supporting statehood by far than were opposed. The opposition came mainly from the canned salmon industry because they feared local control of the fisheries. They had had a favorite position with the federal agencies in the fisheries field and they were opposed and the gold mining industry was opposed because they feared that statehood was going they forgot it was going to bring more taxes and make their operations more difficult economically. And so the newspapers here in Southeast, which was the center of the fishing industry, except for Bristol Bay, the local paper in Juneau opposed and one of the two papers in Ketchikan was opposed.

Vic Fischer: As usual there were those who testified that Alaska cannot afford to become a state. That we can’t support statehood and Senator Clinton Anderson of New Mexico said well that sort of makes me think of marriage. Can people really afford to get married if people approach that on strictly the financial basis? Most people might never get married, but there are other issues involved and he was wonderful in sort of taking care of that argument that we cannot afford it

George Sundborg: Frank Heintzleman of course when he was governor he was in a very difficult position because there was a large group at Anchorage, which had most of the population of Alaska. It was all for statehood. And they were just beating the drums for it you know. And Frank was trying to soft pedal that. And Eisenhower, the President, came out with a proposal to partition Alaska and only let certain part of Alaska be admitted as a state. And people blamed Heintzleman for this and so on.

George Rogers: I worked for him briefly for about two or three years. That’s another story, but he said that he was afraid that we couldn’t afford to support statehood. I said I agree with you, but that we are not going to be able to afford statehood until we get it because we don’t have control over our own destiny. So the legislature absolutely everything they did had to be approved by the congress. We couldn’t incur any indebtedness. There were lots of things we couldn’t do and you were in a straight jacket. You had to get rid of that. We had no lands that we could draw upon to get revenues from. So statehood would bring those things in. So I tried to argue with him that statehood would make it possible to afford statehood. He didn’t quite buy that. …

But of course he was Republican and the Republicans as a whole were anti-statehood. Although during the Constitutional Convention they – very conservative Republicans worked very well on that.

JAY HAMMOND:

Actually I had voted against statehood.

My reasons were simply this that with our tiny population – I don’t know it was only about 70,000 people and we had no economic potential immediately on the horizon, fishery, timber, mining, trapping all gone down hill. And I felt with our tiny population and first our ability to finance and administer were very dicey. And I said that with our small population virtually any idiot that aspired to public office is liable to achieve it. And a lot of folks subsequently have said yes and you proved it on more than one occasion. I did not oppose it idealistically, but I also was affronted by the fact that you couldn’t even look at such things as commonwealth status, which seemed to have some interesting aspects worthy of examination, but the very suggestion of looking at alternatives branded you as a crackpot or communist or some sort of loathsome creature. And very few openly opposed statehood. It was kind of the kiss of death to do so.

But one time I had an interesting experience subsequent to my service in the legislature when a number of us were standing around some unanticipated expenditure had crawled out from the rocks and there were eight legislators there. And one guy said huh, we almost went bankrupt the first – more people left the State than arrived by any other means other than the birth canal and the economy was going downhill badly. We were on the edge of bankruptcy and something as I saw crawled out of the woodwork unanticipated and some guy said well I never really was too hot on this statehood business and the other guy says no neither was I and matter of fact I voted against it. Six out of the eight legislators voted against it. But I was the only one stupid enough to publicly announce it.

Now was it a mistake, no. I was wrong. We did have and do have the ability to finance and administer, but the jury is still out as to whether we’ve succeeded in doing so.

Intertitle: Statehood

Katie Hurley: During the convention I don’t think anyone had any conception that it would happen so quickly. Looking back it is amazing the it was just two years and they thought – that’s why hardly anybody of the lobbyists came to the convention. They thought it was an exercise in futility. Too bad those guys are so carried away that they are spending all that time writing it – the constitution.

Vic Fischer: Statehood was inevitable. I mean we all felt that. Gallop polls showed time and again and again that more than two-thirds of the people in the United States supported statehood. Across the board editorial policies of major – with newspapers and local newspapers around the United States supported statehood.

Vic Fischer: The frustration became so horrendous when Congress would come right up to the edge and not act to grant Alaska statehood, grant Hawaii statehood, because it was always these political arguments. There will be more Republicans versus Democrats and the division being close Alaska or Hawaii could make a difference. The same thing on the civil rights issue. It was a matter of the majority of the US senators supporting statehood but the filibuster power was with the southern anti-civil rights senators and on the house side they controlled the Rules Committee so that statehood bills just couldn’t successfully move through both houses.

Jack Coghill: Hawaii had had their Constitutional Convention and they were getting ready and they wanted to have statehood. Well the thing was that the reason why we’re the 49th state and they are the 50th state is that in those days Hawaii was very Republican. It was the Dole Company and the big farmers and stuff like that.

Maynard Londborg: At that time the territory was very strong Democrat, which was kind of interesting because that was one of the blocks that we thought we’d have a hurdle with the United States Senate was the Republicans didn’t want Alaska in because that would give another solid Democratic candidates that would be in there and senators and representative and it would just add that many more.

Vic Fischer: It was just sort of a phenomenal victory when finally in 1958 the house approved and then finally the senate approved. And senate action probably came thanks to Lyndon Johnson who, thanks to Bob Bartlett was convinced to move the senate in that action.

Katie Hurley: Bob Bartlett had called to let me know that this was going to be the day, some time that day he was sure it was going to be the vote cause they had been arguing it and he was quite sure. …

And we dashed in. I parked the car and ran up the steps, two at a time, I was so excited to get up there.

To me that was the day that we became a state because there had been no much work and we had been so long. I had been in Washington in 1950 when the house had passed the state – I was in the gallery. I was with Mary Lee Council. Bob had seen to it that we were there when they passed the statehood bill in 1950. So this is like eight years later. So that was very exciting to be there.

George Sundborg: The statehood act was signed by the President on January 3, 1959 and by that time I was in Washington, DC and we were in business.

And I think that statehood sort of lifted us from the colonial status because we had rights, we had things that we could enforce, we could control our own destiny.

George Sundborg: If we go broke it is going to be our own fault. And that’s very good for a democratic society.

But I believe just on its – the grounds of self-government, statehood was a tremendous worthwhile goal and had they not discovered petroleum up there, we would have made it by somehow.

George Sundborg: It was a great time to be in Alaska. Things were improving. Statehood was coming, it was in sight you know. We were winning.

Closing titles.

Jack Coghill – Recorded January 26, 2004, in Nenana.

Vic Fischer – Recorded September 26, 2003, at Vic Fischer’s home in Anchorage, Alaska.

Jay Hammond – Recorded January 4, 2004, in Anchorage. Died August 2, 2005.

Katie Hurley – Recorded February 4, 2004, at Katie Hurley’s home in Wasilla. .

Maynard Londborg – Recorded March 31, 2004, at Maynard Londborg’s home in Denver, Colorado. Died September 5, 2004.

George Rogers – Recorded September 22, 2003, at George and Jean Rogers’ home in Juneau. Died October 3, 2010.

Tom Stewart – Recorded September 23, 2003, at Tom Stewart’s home in Juneau, Alaska. Died December 12, 2007.

George Sundborg – Recorded October 7, 2003, at George Sundborg’s home in Seattle/Magnolia, Washington. Died February 7, 2009

Interviews conducted by Dr. Terrence Cole, UAF Office of Public History

Episode 10: Jay Hammond (part 2)

Episode 10: Jay Hammond (part 2) Episode 9: Jay Hammond (part 1)

Episode 9: Jay Hammond (part 1) Episode 8: George Sundborg

Episode 8: George Sundborg Episode 7: Katie Hurley

Episode 7: Katie Hurley Episode 6: George Rogers

Episode 6: George Rogers Episode 5: Maynard Londborg

Episode 5: Maynard Londborg Episode 4: Jack Coghill

Episode 4: Jack Coghill Episode 3: Tom Stewart

Episode 3: Tom Stewart Episode 2: Vic Fischer

Episode 2: Vic Fischer Episode 1: The Constitutional Convention and Statehood

Episode 1: The Constitutional Convention and Statehood