One of Alaska’s first positive cases of COVID-19 was a person who’d been to a grocery store while they were infectious.

Normally, this wouldn’t be cause for concern, given the need for prolonged exposure to significantly increase a person’s risk of getting sick. But in this case, a long wait at the checkout kept the infectious person in line for more than half an hour — potentially exposing the people behind and ahead of them to a deadly disease.

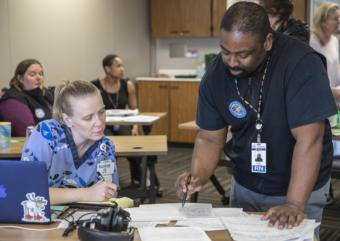

It fell to Drew Shannon, a nurse employed by the Anchorage Health Department, to find those unwitting “close contacts.” Armed with a receipt supplied by the sick person, he worked with the store to reach the two other people from the checkout line, then made sure they were quarantined to keep the disease from spreading further.

Both have now finished their quarantine without developing symptoms.

Shannon’s work is known as “contact tracing,” and it’s a critical piece of public health officials’ battle against COVID-19. The task entails finding, quarantining and monitoring people exposed to a disease, along with identifying the infection’s original source.

In Alaska, the job falls to a network of trained workers, many of whom are epidemiology staff and public health nurses from the state Department of Health and Social Services. In Anchorage, eight city nurses take on many of the cases, with support from school nurses who were reassigned after classes were canceled. One former city nurse even came out of retirement to help.

While public health experts say contact tracing is crucial to keeping COVID-19 in check, the nurses’ regular phone calls and check-ins also bring a measure of humanity and comfort to one of the groups of Alaskans with the highest risk of developing the disease.

“It’s nice to have somebody checking to see if you’re okay,” said Robert Bowles, a 60-year-old Juneau man who tested positive for COVID-19. “The fact that they were calling every day felt good.”

Contact tracing is part of what epidemiologists call “containment” — the essential work of determining where the virus already is so that further spread can be slowed.

In Wuhan, the Chinese city where the COVID-19 pandemic began, more than 1,800 teams of epidemiologists, each made up of at least five people, traced tens of thousands of contacts a day, according to the World Health Organization. Up to 5% of contacts were subsequently confirmed to have the disease.

Containment is not the only front on which authorities fight COVID-19. But the work is particularly important in Alaska because of its dispersed and remote villages that lack advanced health care infrastructure, said Joe McLaughlin, the state’s top epidemiologist. That means Alaska will continue its focus on containment even if the number of cases escalates to the point where “widespread community transmission” tests its tracking capacity, McLaughlin said.

For now, officials say they have enough manpower to handle the cases confirmed each day.

State nurses were checking in with more than 60 people in Ketchikan and 20 in Juneau in recent days, according to Sarah Hargrave, a Juneau-based state nurse supervisor. Anchorage city and school nurses, plus support staff, were tracking 126 close contacts and 56 confirmed cases of COVID-19 on Saturday, according to the municipal health department. (Anchorage’s figures may not include people in the city who have recovered or are being monitored by other agencies, like the military.)

Contact tracing starts with a positive test result, which is assigned to an individual nurse or trained public health official for an investigation.

Many of the state and city public health nurses have similar experience investigating other illnesses, such as tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections like syphilis or gonorrhea. But many of those cases are easier to track than COVID-19, which can be transmitted through sometimes-invisible respiratory droplets.

“Gonorrhea, for example, the mode of transmission is pretty clear,” said Shannon, the Anchorage nurse. “With COVID-19 respiratory droplets, that could be a lot more people.”

The investigator starts by calling the patient with a series of questions about their travel and who they’ve spent time with.

In countries without the U.S.’s privacy protections, public health authorities have reviewed cellphone data, surveillance camera footage and credit card transactions to help with their contact tracing.

In Alaska, nurses can use Facebook or other social media to locate a contact, or they might ask for help from a business. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a system to find people who sat on a plane near someone later diagnosed with COVID-19.

Otherwise, information comes mostly from patients, who are generally eager to cooperate, said McLaughlin, the state epidemiologist. Their close contacts, he added, are “their friends, their family members, their co-workers.”

“They really want to help protect them,” he said.

Close contacts are defined as people who spent more than 5 or 10 minutes within six feet of the patient during their infectious period; they’re asked to quarantine for two weeks. After developing a list, nurses and support staff will then call each patient and close contact once or twice daily, asking for temperature readings and other symptoms.

Once a nurse has established a rapport, they might switch to email or texting, or even the Whatsapp messaging program. Some of the Anchorage nurses have been speaking in Spanish with families, and they’ve also enlisted a Hmong translator.

But the work goes beyond collecting data on symptoms. Nurses have helped get food to people’s homes if they’re stuck in quarantine, and they can support people emotionally at a time when they’re isolated, vulnerable or afraid.

“Some people are scared. They’ve heard the horror stories,” said Hargrave, the state nurse supervisor. “A really important part of getting through this is having some social connection and support, and to not feel alone. And we’re happy to provide that when we can.”