During the summer, toxic algae whip through marine currents in Southeast and are consumed by filter-feeding bivalves, like mussels. One such algae is an armored dinoflagellate called Alexandrium.

Alexandrium was common only in summer months previously, but now may be present in the winter, too.

“Blue mussels are kind of like the pigs of the sea. They never stop feeding,” said Chris Whitehead, environmental program manager of the Southeast Alaska Tribal Toxins partnership.

Blue mussels are one entry point for Alexandrium to work its way up the food chain. The algae cause paralytic shellfish poisoning, affecting animals that eat blue mussels, like Dungeness crabs and humans.

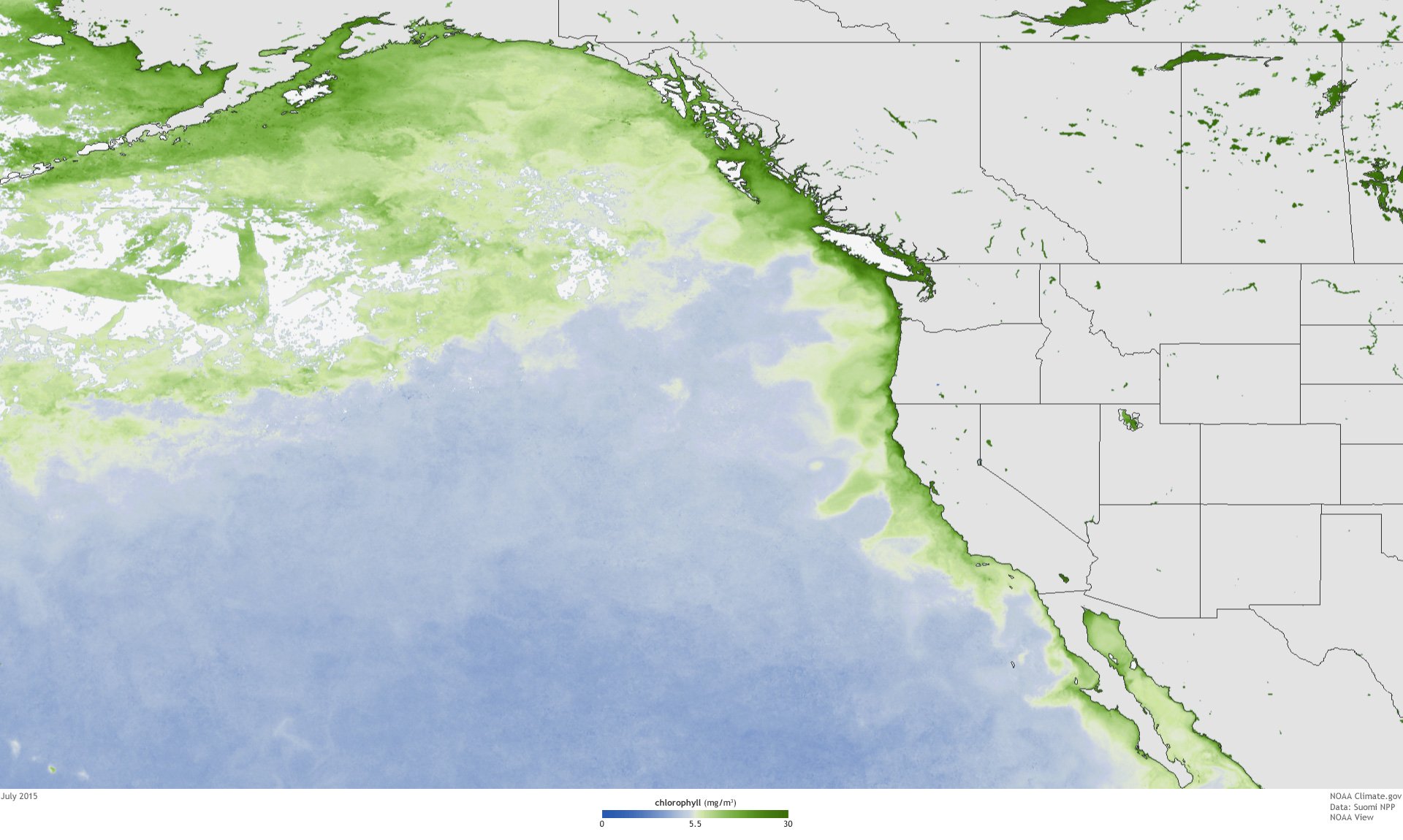

And another harmful algae, Pseudo-nitzschia, is circulating in the Pacific too.

From California to Washington, commercial Dungeness crab fisheries were closed or delayed this fall because of the Pseudo-nitzschia bloom. Some species of the algae produce domoic acid, a neurotoxin.

The Southeast Alaska Tribal Toxins partnership and University of Alaska Fairbanks oceanographer Liz Tobin have created a program to test for blooms and toxicity in Southeast.

September SEATT data from Juneau indicates Pseudo-nitzschia was present at Amalga Harbor, Auke Bay, Eagle Beach and Point Louisa. According to Tobin, the presence of Pseudo-nitzschia has been documented in Southeast but there is no evidence of the harmful domoic acid.

Whitehead, with the tribal partnership, said the Pseudo-nitzschia found in Southeast could be a different, nontoxic species than the one documented down south.

Moving up the coast, “somewhere in Canada everything changed,” he said. “As soon as it left the West Coast of Washington and moved into British Columbia something switched.”

At the Juneau testing sites monitored this September, Alexandrium was present at all locations except Eagle Beach, although there was no bloom.

In the past, it was considered safe in Southeast to consume bivalves harvested from September through April, because Alexandrium was uncommon. But there was a case of PSP documented last December in Juneau, according to Whitehead.

While the monitoring project for toxic algae is in its infancy, researchers believe future studies will detect blooms before they become harmful to people. Monitoring plans include testing bivalves and dungees for the toxins.

A recent study from Haines found the guts of Dungeness crab tested higher for PSP than Food and Drug Administration limits for human consumption. While most people don’t eat the guts, the results may be worrisome for crab consumers.

Christine Woll fishes for dungees by kayak from North Douglas. She drops a collapsible pot each spring and paddles to it weekly throughout the summer to retrieve her catch. She guts each crab and keeps the meat only.

Woll used to make crab stock out of the leftover carapace, but she has stopped.

“If there are extra parts of the crab left there on the shell that might be toxic, that would be a place that I might get in trouble,” she said.

According to oceanographer Tobin, as far as research can tell, only consumption of infected dungee guts, not the meat, is toxic for human consumption when it comes to PSP.

But domoic acid accumulates in crab meat.

Tobin said a few environmental factors are responsible for prolific algae blooms.

“Temperature seems to be a driving factor, but considering that this year we had anonymously high sea surface temperatures in the Juneau area, and we didn’t see a bloom (of Alexandria), that indicates that it’s not the only contributing factor,” she said.

Wind speeds, freshwater runoff and nutrient loading could also affect the blooms.

An unusual mortality event of 18 endangered whales near Kodiak has raised concerns toxic algae could be harming whales, too.

All of these questions call for further monitoring by the tribal partnership.

The group’s new biotoxin lab in Sitka will take a leap forward in early detection of harmful blooms. The monitoring program could allow documentation of toxins before they work through the food chain from mussels to crabs and humans.