In 2013, Congress authorized the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian to establish a national veterans memorial for Natives.

The Alaska community consultations of that national effort wrapped last week.

More than 86,000 Native Americans and Alaska Natives served in the armed forces in World War II and the Vietnam War, and about 31,000 currently are active duty, according to Department of Defense estimates.

Eileen Maxwell is a spokesperson for the museum.

“They’re patriots. Native Americans are some of the most patriotic Americans in this country. When their land is under danger or siege, they are the first to sign up and to volunteer and to make themselves available to protect our homeland.”

An advisory committee and the museum have been conducting community consultations to seek input and support for the memorial, to find out what Native veterans want to see in a national tribute.

Maxwell says that Native Americans have served in the U.S. military since the American Revolution.

“In higher numbers than any other ethnic group per capita,” she said. “It is quite an amazing tribute to Native Americans and needs to be recognized with a national memorial in the nation’s capital.”

Alaska Native veterans, community members and museum representatives met recently at the Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau.

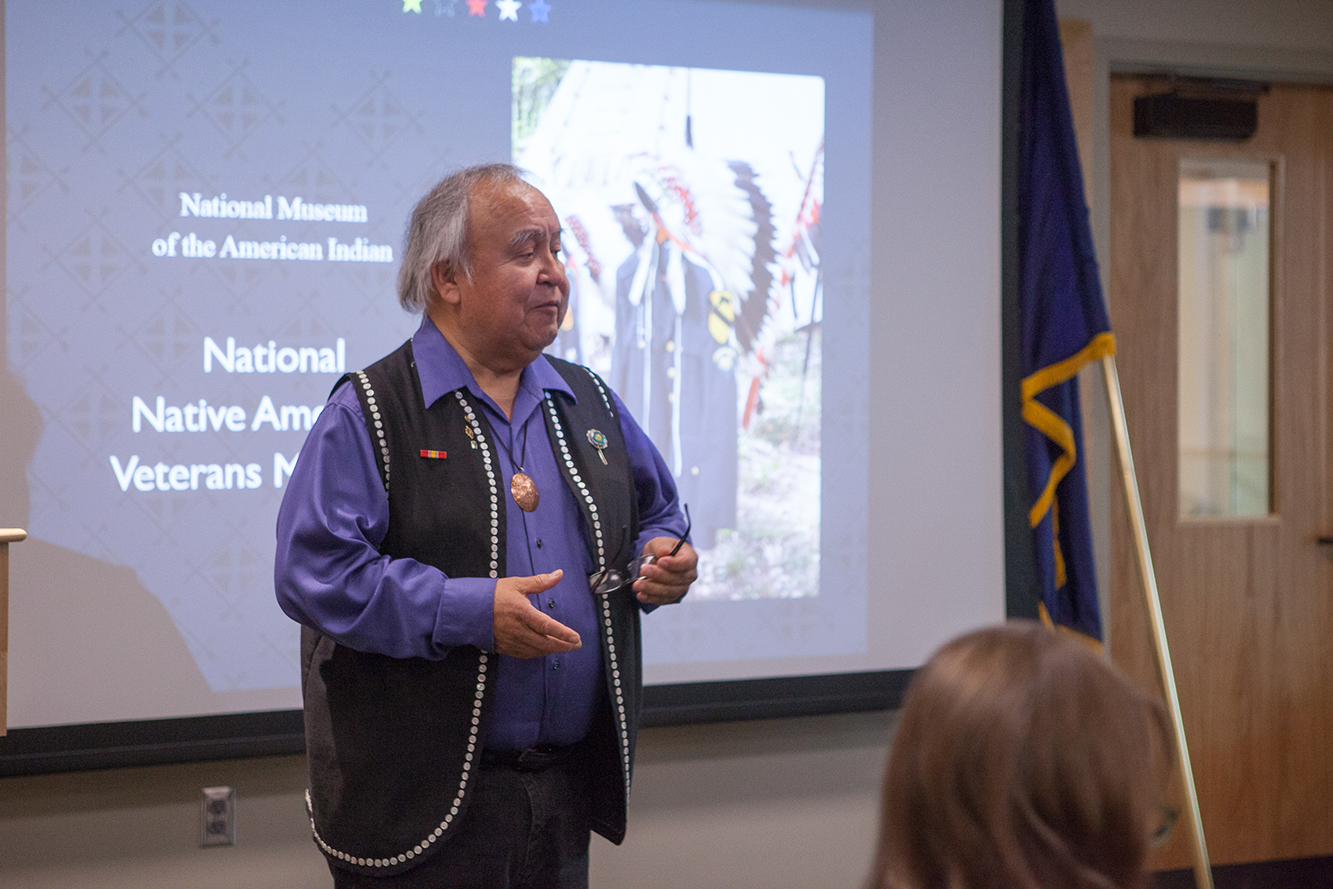

Ozzie Sheakley was one of the attendees. He commands the Southeast Alaska Native Veterans and has researched and presented on Tlingit code talkers during World War II.

“There wasn’t really recognition about the Indian peoples in the wars,” Sheakley said. He has researched and presented on Tlingit code talkers during World War II.

The code talkers were trained Native soldiers who sent unbreakable codes based on indigenous languages.

“To me, it’s like the help of our people shortened the war. … Because of that, I feel like we were a big part of, especially, World War II.”

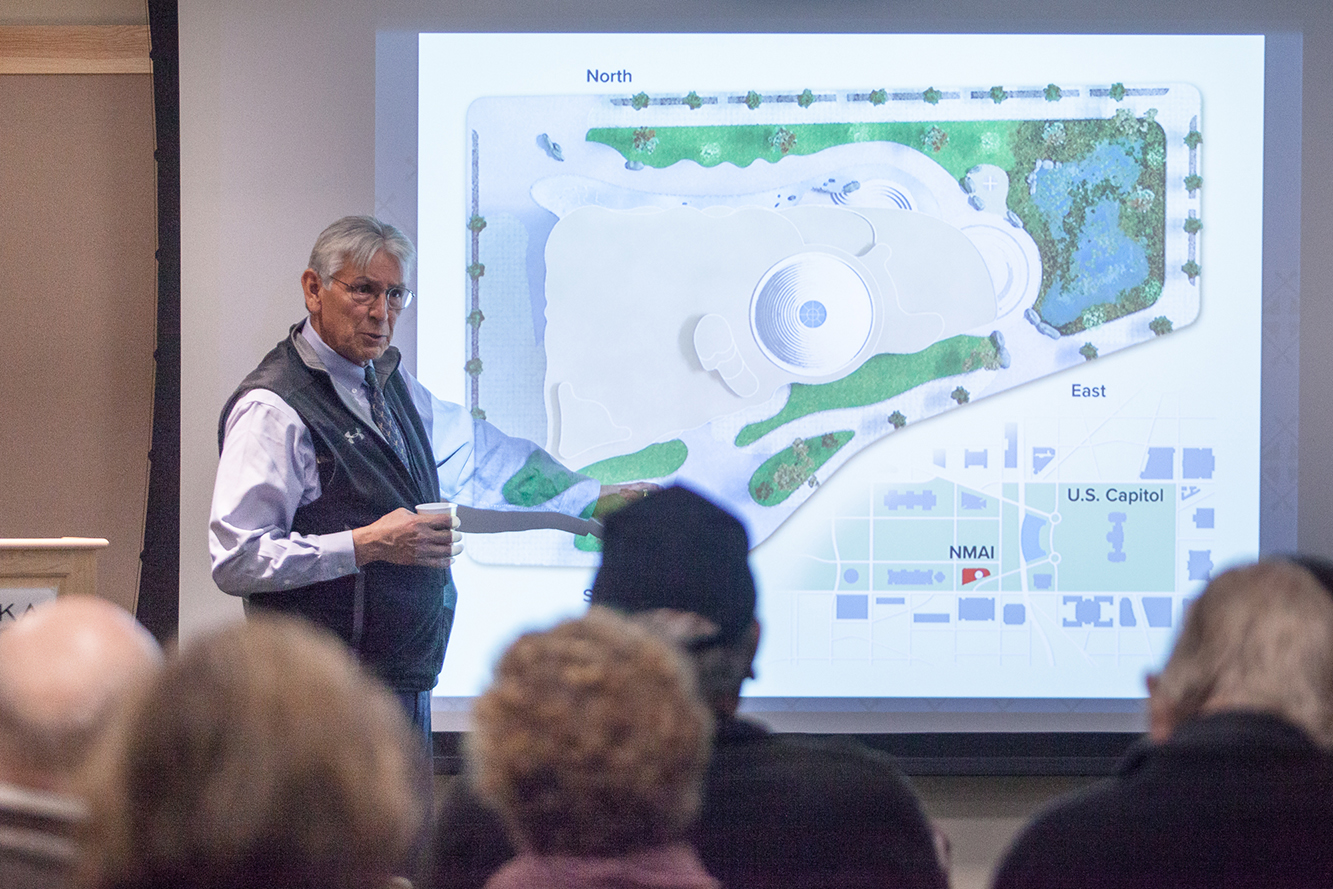

The museum estimates the budget for the memorial at $15 million, which includes long-term maintenance and associated educational programs. Construction and implementation will be about half of that.

“There’s like 33 different tribes that are putting their ideas together,” Sheakley said. “We just want to make sure that everyone that was in the service is recognized” including the Merchant Marines and the territorial guards.

Groups met in Fairbanks in October. Juneau was the penultimate stop. The last meeting was in Anchorage at the Alaska Native Heritage Center.

Eleanor Hadden, curator of collections and exhibits at the center, says few attended, but it was an emotional meeting as families and veterans talked about the history and hardship of their Alaska Native relatives who served.

Hadden, whose Native name is Aan-Kee-Naa, is Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian originally from the Ketchikan area. She said her family has a long history of serving in the military, including her father who served in Korea and her spouse, whose career in the Air Force has spanned 24 years.

She said at least one person asked that the memorial not portray war, but survival and life. Another idea was to include the family and community who supported the soldiers when they returned home.

Sheakley says coming up with a unifying memorial could prove difficult.

We know it’s going to be hard for them to make a choice because they’re meeting with all the tribes,” Sheakley said. “It’s a small area they’re going to be using. To me, it’ll be good if they recognize every tribe that there is, but because it’s going to be a small area they can’t do that.

Sheakley says one idea is to include the various code talker medals.

“What they should do is get a copy of every code talker medal and put it around the side because that’s from every tribe,” he said.

Congress recognized 33 Native groups in 2013 for their efforts during world wars. Sheakley accepted a Congressional Gold Medal on behalf of Central Council of the Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

Five individual Tlingit men — Jeff David, Richard Bean Sr., George Lewis, and brothers Harvey Jacobs and Mark Jacobs Sr. — all deceased, were honored with silver medals.

The memorial design will be selected through a juried, international competition to launch in the fall.

The memorial will be on grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington. It’s expected to be dedicated in 2020.

You can find out more about the museum at nmai.si.edu.