In the 1950s and ‘60s, the “Native church” in Juneau was packed for holiday services. Seven days a week it housed civic and church-related gatherings.

The Memorial Presbyterian Church served a predominantly Lingít congregation, true to its 1887 roots in a town that practiced segregation in restaurants and movie theaters into the mid-1940s.

Then, to “end segregation,” the Alaska Presbytery and the Presbyterian Board of National Missions closed the thriving Native church in 1962.

Maxine Reichert, Lingít and Athabascan, recently told the Northern Light United Church congregation the closure meant the loss of the Juneau Indian Village’s support system, “the heart of the community,” just as it was undergoing even greater trauma. The Juneau Indian Village, and just across the bridge, the Douglas Indian Village were destroyed for 1960s-era urban renewal and development.

Now the Presbyterian Church USA, Northwest Coast Presbytery, and Ḵunéix̱ Hídi Northern Light United Church have committed to pay nearly a million dollars in reparations for the harm and pain the closure caused.

The amount is significant but what it will be used for is even more so. Most of it is to go to programs to promote healing, cultural preservation, and education.

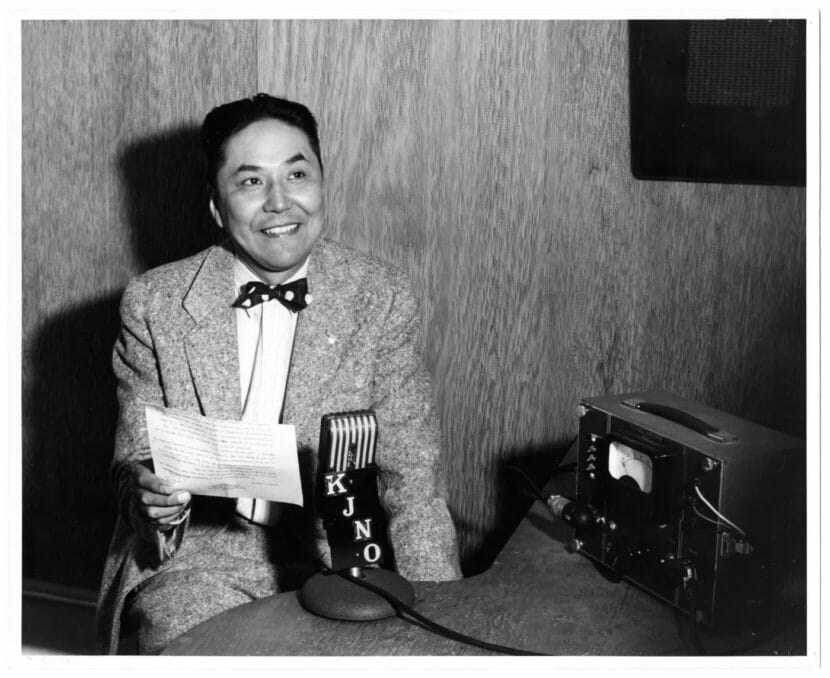

We’ll get into that some more but first, let’s go back to 1940, when pastor Walter Soboleff, Lingít, held his first service in Memorial Presbyterian Church.

Only he, his wife, and one friend attended.

But he was brilliant at growing a congregation. Soboleff advertised in the newspaper and broadcast his sermons on the radio. He reached out with hundreds of letters of support and encouragement to acquaintances, parishioners, and prison inmates.

The church offered Bible study, choir practice, prayer groups, and teenage fireside chats. It was open for day care, Girl Scout meetings, and health checkups. It housed visiting basketball teams from surrounding predominantly Lingít, Haida, and Tsimpshian villages.

The church “was an extension of our family, our extended family,” Judy Franklet, Lingít, said in a 2019 interview.

Franklet remembered, “playing with friends down in the, we called it the basement, but that’s where they held the potlucks and other activities. And then we had coffee probably right after the worship service. And I remember Dr. Soboleff very clearly giving part of the service in English and in Lingít. That was very special to us… you love to hear your own language.”

Franklet also recalled the day when Soboleff told the congregation the church was closing.

“I just remember I was in a state of shock and when I look back, I’m sure he was hurting. His explanations were just very short,” Franklet said. “It was just like you were hit in the stomach. It was such a surprise.”

Last year, as the Native Ministries Committee of the church began discussing reparations, “I remember one moment in particular,” said Lillian Petershoare, Lingít. “We were talking about the closure of the Memorial church and I said to everyone, ‘You know, what really disturbs me here is that in our research, we have seen that the Presbytery and the national church leaders came to Memorial many times over the years. The women of the church sponsored tea for the regional and the national leader. They were not strangers. They knew this church. They knew the people in this church.’”

She said it was inhumane of church leaders to abandon Soboleff to announce the closure alone.

“Why didn’t they come and have a beautiful ceremony to celebrate the wonderful work of the Memorial church and the Presbyterian church in the Juneau Indian Village? Its predecessor? Why wasn’t there all that circumstance? Why wasn’t there all that acknowledgement? Why wasn’t there that shared grieving?” Petershoare asked.

“If this had been a traditional Lingít setting, there would’ve been all of that protocol. And so there should have been.”

Petershoare said the national officials should have expressed the church’s deep roots in the community and its role in the life of the community. “We felt that profoundly.”

A former minister of Northern Light United Church, Phil Campbell, told filmmaker Laurence A. Goldin in a 2022 interview that as he met Native people, he learned time had not healed the wound of the church’s closure “even though it had been almost 50 years.”

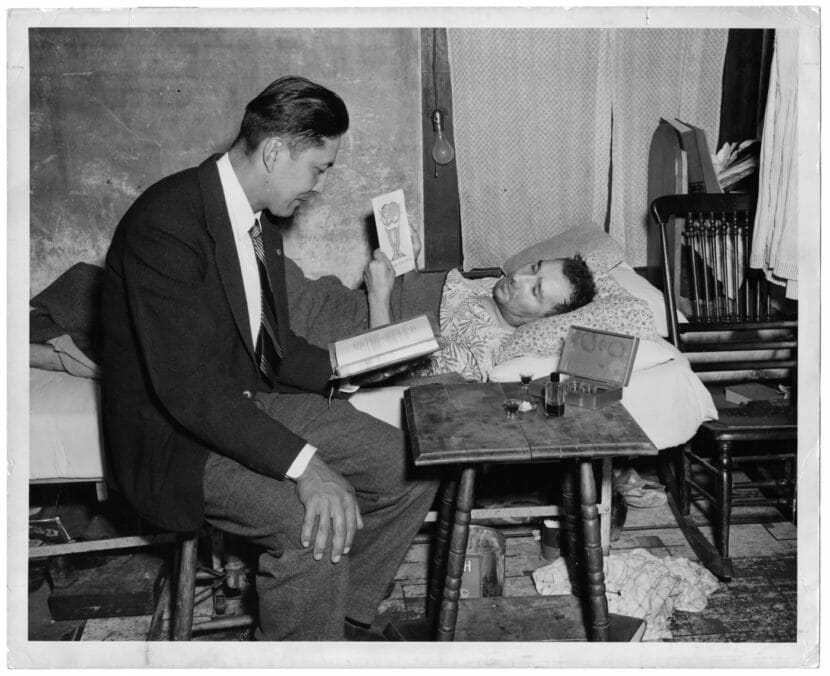

“I did have one occasion to ask Dr. Soboleff about it. I was visiting with him a couple of months before his death as it turned out … as I began asking about this, I saw the pained look on his face. He was saddened and troubled by the question, and said in effect, ‘I don’t know why they closed it,’” Campbell said.

At the same time the Presbytery said it couldn’t afford to continue to subsidize the Native church, it loaned $200,000 to a White congregation to build a new church just a few blocks away from Memorial.

The Presbytery and Board of Missions advised the Native church members to join the new Northern Light Presbyterian Church. Less than half did. Most joined other denominations or drifted away from church altogether.

In the 1990s, a group of Indigenous members of Northern Light church formed a Native Ministries Committee. With Campbell’s help, in 2021 they wrote an “Overture,” (similar to a resolution) entitled “On Directing the Office of the General Assembly to Issue Apologies and Reparations for the Racist Closure of the Memorial Presbyterian Church, Juneau, Alaska.”

The Overture stated: “The forced closure of this thriving, multiethnic, intercultural church was an egregious act of spiritual abuse committed in alignment with the prevailing White racist treatment of Alaska Natives, statewide, and of Native Americans, nationwide.” It was distributed nationally to Presbyterian churches and discussed in regional and national gatherings of church leaders.

The Presbyterian Church USA adopted the Overture unanimously without amendment at its July General Assembly. In adopting it, the church acknowledges its justification for the closure ”merely substituted assimilationist racism for the previous practice of segregationist racism.”

The Overture includes a list of actions for reparations.

The church, with regional and national leaders present, will acknowledge, confess, and apologize to the late Walter Soboleff and his surviving family members “for the act of spiritual abuse committed by the Presbyterian Church’s decision of closure, which was sadly aligned with nationwide racism toward Alaska Natives, Native Americans, and other people of color.”

By adopting the Overture, the church committed to become engaged and accountable for “interactions with churches of primarily people of color congregations so that difficult decisions about support and funding are made in a spirit that recognizes the importance and contributions of these congregations to the Presbyterian Church (USA), which outweigh superficial considerations of their membership numbers or perceived lack of financial resources.”

The Overture also encourages Presbyterians nationwide to donate funds and to renew commitments to dismantle systemic racism and amplify the voices of people of color.

It urges all to continue to walk away from the doctrine of discovery, the idea that when a European nation “discovers” land uninhabited by Christians, it acquires rights to that land.

As one of the first steps in reparations, the church was renamed Ḵunéix̱ Hídi (people’s house of healing) Northern Light United Church.

As the successor and beneficiary of the Memorial Church’s closure, Ḵunéix̱ Hídi committed $350,000 for reparations, which will include the creation of art and remodeling of the Ḵunéix̱ Hídi church to be more welcoming to people of color and to reflect southeast Native cultures.

Money will go to scholarships and programs for revitalization of southeast Alaska Indigenous languages. Ḵunéix̱ Hídi will also gather oral histories and develop curriculum to teach the history of the Memorial Church.

Ḵunéix̱ Hídi will also pay for a “highly visible recognition” of the Memorial Church at its former location.

Reichert said additional money will go to “Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimpshian languages, (and) scholarships for students who want to go into the seminary to become ministers.” For these and other efforts, the church has committed nearly a million dollars.

The reparations were accepted by the local congregation, then at the regional and national levels. The commitments call for some soul searching, with the understanding that healing from racism is an ongoing process.

Ministries committee member Myra Munson said the history of racism, of slavery, of what happened to Indigenous people, and actions against LGBTQ people, “all of these things create a burden that maintains an “us and other” approach to the world and to each other in the community and at large nationally, and internationally. Every step we take that overcomes that or reduces it helps us all live in a healthier way and healthier place.”

Reichert said she was relieved when the General Assembly voted to accept the Overture. “It felt like Walter Soboleff and what he had been doing with Memorial Presbyterian church, he had been vindicated and, and I felt just really good about that.”

The Presbyterian church has a history of racism, perhaps most strongly exemplified in the boarding schools it ran to assimilate Indigenous children. The boarding school experience traumatized generations of Native children and led to the near loss of Indigenous cultures and languages.

However, Reichert said Indigenous people, “they have churches still existing, like in the Dakotas where they have a number of churches that are run by Native ministers. And a lot of them have not graduated from seminary and they have very little funding for those churches, but the Native people are still going to them and they still want that religion. But they want it in their own culture.” The reparations will help make that happen for Southeast Alaska Indigenous peoples.

This article draws on one written in 2019 for “First Alaskans” magazine. The author also narrated a short film, “The Native Church,” on the subject.