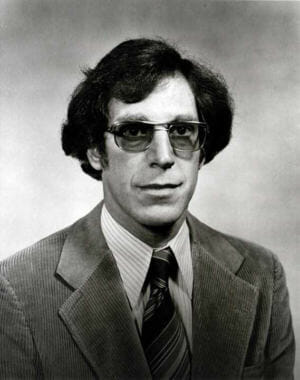

Former Alaska Attorney General Avrum Gross died May 8, 2018, at the age of 82. He had pancreatic cancer.

Republican Gov. Jay Hammond appointed the East Coast Democrat in 1974 to be the state’s top attorney. It was a seminal time for the Alaska Permanent Fund and Gross played a key role.

Avrum Gross was born Feb. 25, 1936, in New York City and grew up in New Jersey. As a child, Gross went to the Juilliard School to study violin. He talked about the experience in a 1986 KTOO television interview.

“I was quite good, as a matter of fact,” he said. “I was driven so hard at it, that when I finally left high school and went to college, I stopped playing the violin for 15 years. I just stopped. I never picked it up again. I couldn’t stand it. All I could think of was getting up at 5 in the morning and practicing, having my father yelling at me that I wasn’t doing it right.”

His father was a Columbia Law School lawyer. Gross earned his law degree at the University of Michigan. He moved to the young state of Alaska in 1961.

“It was sort of the idea of taking a couple of years off for a lark, and then going back to work in New York, where I always thought I was gonna work,” he said. “I decided, well, why not try Alaska? I always liked to fish, the idea was come on up here, work a couple of years and have some fun for a couple of years, and then go back and work at a real job. And I came up here, and after two years, I was hooked.”

While working for the Legislature, Gross met Hammond, then a lawmaker representing Naknek.

Through the legislative process, Gross said Hammond created a position for a special counsel on fisheries matters in the Department of Law. And Gross was hired for the job. A few years later, he went into private practice.

His oldest daughter, Jody Gross, remembers her father in the 1960s in Juneau as, “this Jewish guy from New Jersey.”

She said he was sympathetic to the hippie movement, talked civil rights in the family living room with local high school kids, and caused an uproar by delivering a politically provocative high school graduation speech.

By 1974, Alaska had elected Jay Hammond governor.

The Republican described the blowback after he picked Gross for attorney general in a 2004 interview for 360 North.

“Then a lot of folk cussed me out for appointing Av Gross. And I said, ‘Well, I think it is the obligation to appoint the best legal talent available to fill position of attorney general. And to me Av Gross is right up there at the top, even his cohorts and colleagues agree.’ ‘Oh well, yeah, he’s a brilliant attorney but he’s a Democrat!’” Hammond said with a laugh. “You know, long-haired, hippie-type Democrat from New York.”

Hammond stuck with his pick, and Gross said he didn’t have to sacrifice his principles to work with the governor.

“The best advice you can give a governor, for instance as attorney general, is the truth,” Gross said. “If you tell the governor what the law really is, you keep him out of trouble. If you fudge the law because you think you’re going to help the governor or give him some political, you know, advantage on a day-to-day basis or something, in the end, he inevitably gets into incredible trouble. And you’re responsible for it.”

For example, Gross recalled convincing Hammond to veto a bill the Legislature passed to establish the Alaska Permanent Fund.

“Hammond had fought for the permanent fund all his life, he really felt strongly about it,” Gross said. “I called him up and told him that the bill was unconstitutional.”

Creating the permanent fund meant creating a dedicated fund, which can only be done through a constitutional amendment.

“He was so upset,” Gross said. “He said to me, ‘I want to sign this bill. I so much want to sign this bill. Can’t you find some way?’ And I said to him, ‘No, I can’t find some way. It is unconstitutional, you have an obligation as a governor to veto this bill.’ … But, he did. He reluctantly, very reluctantly, vetoed the permanent fund bill.”

That was 1975. Then, Hammond introduced a constitutional amendment that lawmakers and the people did pass the following year to lawfully establish the permanent fund. Gross said Hammond was better for it.

Gross covered a lot of other legal ground in his public career, including:

- Banning state prosecutors from plea bargaining in a policy experiment still studied decades later.

- Defending the Division of Elections in a contested gubernatorial primary recount. At one point, Gross called this Alaska Supreme Court case his proudest accomplishment. He said it was a test of his integrity because his duty was to defend the state’s elections, but his boss’s re-election was on the line.

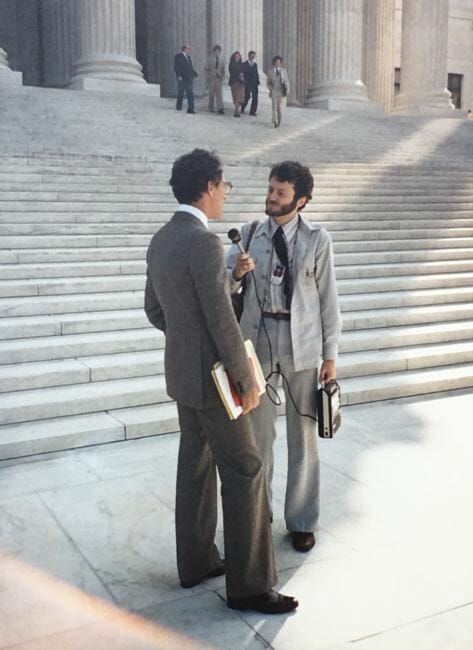

- And, defending the initial permanent fund dividend program, which rewarded longer residency in Alaska with bigger dividends. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually struck it down.

Gross left the attorney general’s office in 1980 — though he kept working the protracted PFD case until the final decision in 1982 — and returned to private practice in Juneau.

He also got back into music after his brother reintroduced him to his violin through fiddle music.

“I dusted it off, and I opened it up and I started to play,” Gross said. “I loved the music. And it was sufficiently different than the classical music that I’d been raised on that I didn’t hear, you know, my father over my shoulder with all the bad vibrations that caused. So I could enjoy my talent and enjoy my training so long as I was playing a different kind of music. … It’s given me an immense amount of joy.”

He played in band called the Grateful Dads, local festivals and the Southeast Alaska State Fair’s fiddle contest.

Gross also bought a historic cannery across Chatham Strait from Angoon.

Jody Gross said he used it as a summer home, family retreat and fishing hole. “That’s where he wanted to die,” she said.

Her father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer about 16 months ago and declined treatment.

“My father’s passion, in the end, even in some of his last words were in response to something I said. He said, ‘No Jody, the most important thing is to always keep your fishing rod tipped up.’ Because, that’s really how he talked. He was in his element when he was fishing.”

He died May 8, 2018, at the cannery in the company of close family members. Alaska flags flew at half-staff for him last month. No other public memorials are planned.

Avrum Gross is survived by his ex-wife Shari Gross Teeple of Seattle, ex-wife Marilyn Holmes of Juneau, partner Annalee McConnell of Chatham; brother Benedict Gross of San Diego, sister Ruth Picker of Virginia; children Jody Gross of Seattle, Alan Gross of Petersburg, Elizabeth Gross of California, and Claire Gross of Juneau; and five grandchildren.