When commercial fishermen spool out long lines in pursuit of sablefish— better known to consumers as black cod — seabirds looking for an easy meal dive to steal the bait off the series of hooks.

Some unlucky birds get hooked and drown as the line sinks to the deep. And when the drowned bird is an endangered species such as the short-tailed albatross, it triggers scrutiny.

“Just one was all it took. Yeah, just one,” said Amanda Gladics, a coastal fisheries specialist with Oregon Sea Grant. “Because they are endangered there is a lot of scrutiny on every single time any of those albatrosses are caught in a fishery.”

Gladics and colleagues from Oregon and Washington went to sea to determine the best tactics to avoid bycatch and published those in the journal Fisheries Research.

The paper recommends either fishing at night or deploying bird-scaring streamers on a line towed from a mast.

Citing the research, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently directed regulators at NOAA Fisheries to require the West Coast long-line fleet use one of the two options.

The Pacific Fishery Management Council is scheduled to discuss the matter in mid-November and may provide similar recommendations.

Gladics said the changeover from voluntary to mandatory seabird bycatch avoidance measures might take several years to go through the rule-making process.

NOAA Fisheries already requires all longline fishing boats in Alaska waters to employ “bird avoidance techniques” such as streamer lines to avoid killing protected seabirds. Canada requires the same for its West Coast sablefish and halibut long-line fishery.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Washington Sea Grant began giving away free streamer lines to long-line vessels around 2009.

In late 2015, use by the largest vessels became mandatory coast wide.

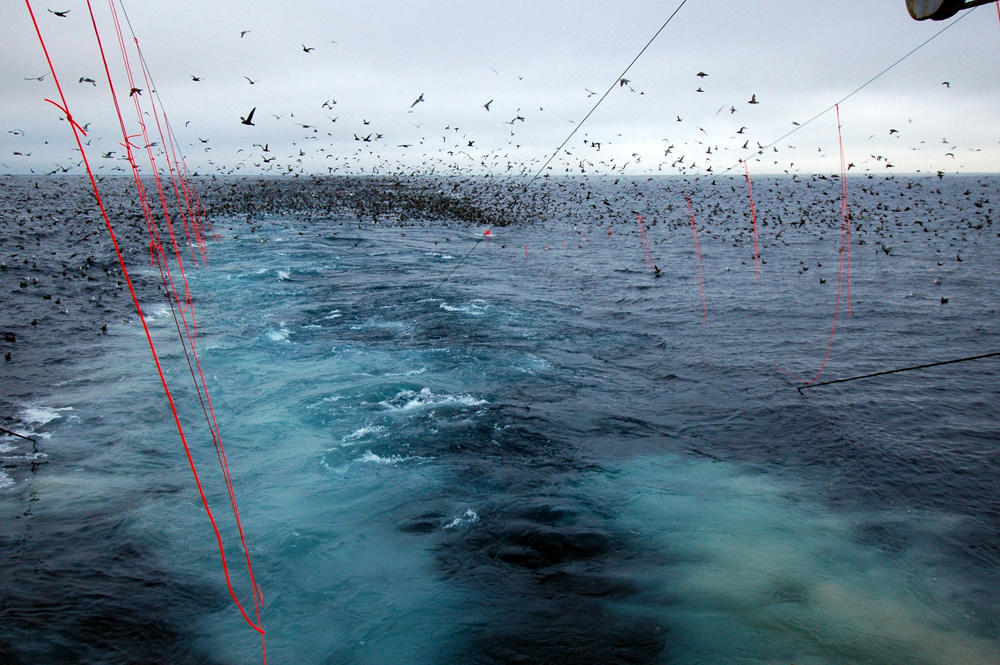

The research team from Oregon Sea Grant, Oregon State University, Washington Sea Grant and NOAA Fisheries judged the bird-scaring lines to be highly effective.

The lines dangle rubber streamers or tubes overhead as the vessel crew deploys their long lines of baited hooks.

“That creates a visual barrier preventing the birds from diving in on the sinking (fishing) line,” Gladics said.

Gladics traveled out to sea with cooperative vessel captains to make observations about how birds interacted with the streamers.

Meanwhile, her co-authors drew conclusions about the effectiveness of fishing at night by studying 12 years of data from federal fishery monitors who rode with the U.S. West Coast fleet in pursuit of sablefish.

“Not only did we find that night fishing reduced bycatch—it did so dramatically,” said co-author Ed Melvin, a fisheries scientist at Washington Sea Grant.

”We found that albatross bycatch was 30 times lower when vessels fished at night (after civil dusk) and target catch was 50 percent higher compared with daytime fishing,” Gladics said.

The study Gladics led focused on vessels from Bellingham to San Francisco who fish the continental shelf. In an email to fishing vessel collaborators this month, she said fishermen and birds could both come out ahead by taking seabird avoidance measures.

“Night fishing isn’t right for every vessel, so that is why it is great to have fishery-specific options that you can do,” she said in an interview Friday in Newport, Oregon.

According to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report published earlier this year, there has been one confirmed case of a short-tailed albatross being killed in long-line gear since 2002 off the Oregon, Washington and California coasts.

Other species of concern caught at higher rates in long-line fishing gear include black-footed albatross, Laysan albatross and shearwaters.

The short-tailed albatross is the largest of the three albatross species found in the North Pacific, which makes it the largest seabird you could encounter off the West Coast, period.

Adults can grow to have an 8.5 foot wingspan. The long-lived, slow-to-reproduce bird has a distinctive bubblegum-pink bill.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature, or ICUN, estimates the world population at about 4,200 and increasing. The short-tailed albatross was federally-listed as endangered in the United States in 2000.