All over Southeast Alaska this summer, volunteers have been conducting bat surveys for the state Department of Fish and Game.

The surveys are being conducted to monitor bat populations regionally.

The data is playing a bigger role in bat research across North America.

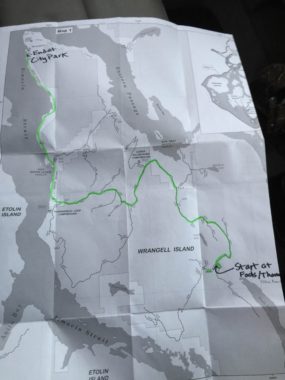

It’s about 15 minutes after sunset on Wrangell Island, and Corree Delabrue is getting ready for a driving survey about 30 miles south of town.

“So what I’m doing right now is putting out the microphone on top of the car, and it’s connected to a bat detector,” Delabrue said. “This microphone has a magnet so it just sits on top of the car. And once it hits 45 minutes after sunset, we will start down the road driving 20 mph and we will let the bat detector do its thing.”

Delabrue works for the Forest Service by day, but tonight she’s a volunteer.

Other volunteers across Southeast Alaska have been conducting these surveys all summer.

A set route for each community is driven weekly with a magnetic microphone, about 2 inches around, stuck to the roof.

As Delabrue drives down the winding dirt roads, there’s not much activity to speak of, until we hit pavement. And, the bat detector starts getting hits.

The data will be sent to Fish & Game after the survey.

The audio will be analyzed, detailing the species of each bat detected, the location and time.

All of these driving surveys are an attempt to learn more about the six resident species in Southeast.

The results play a larger role. They’re funneling into a larger pool of data through the North America Bat Monitoring Program or NABat.

Forest Service a research ecologist Susan Loeb, who founded NABat in 2012, said the state departments of Natural Resources and Fish and Game also have gotten involved.

“The goal of NABat is to document changes in bat populations, abundances and distributions across large landscape scales and across long-time periods,” Loeb said. “From Canada and the U.S. We also brought in people from Mexico and the U.K., people from non-governmental organizations to develop this program.”

The ups-and-downs of populations across the continent will give an idea of how threats such as white nose syndrome, wind energy development and climate change are impacting bats.

White nose syndrome — the biggest threat, a fungus that grows in temperatures below 60 degrees, irritating bats — has killed 6 million in the eastern U.S. and was found in Washington state last year.

“During hibernation, bats drop their body temperature, drop their metabolic rate and they also drop their immune function,” Loeb said. “So the fungus is able to attack the bat. It causes the bat to arouse from their hibernation state. Because of that, they use up a lot of their fat they had stored to keep them throughout the winter. So these bats are dying of starvation and dehydration.”

Bats in eastern North America hibernate in large colonies in caves and mines, which makes it easy for white nose spores to spread.

It’s also easier for researchers to estimate populations.

“For a number of other species, we’re not able to count them in their roosts either in the summer or winter,” Loeb said.

These species are mostly west of the Rocky Mountains and require driving surveys and stationary bat detectors to estimate populations. They roost in small groups under stumps, between rocks, or even in houses. Loeb said NABat just began collecting data form surveys, such as the one in Wrangell.

“At this point, we are just starting to gather the data from 2015 and 2016. Over the next couple of years, we will be looking at that data and get out some status reports,” she said. “Unfortunately, it will take us probably at least five years, if not more, to look at trends in populations.”

Reports will be released on the NABat webpage, which Loeb hopes to have up soon. Currently, NABat doesn’t receive any funding directly, but Loeb said the federal and state agencies contribute their data. She said the program is still working on obtaining long-term funding.