June 2015. It was the only whale that scientists were able to access to get a sample for testing. (Photo courtesy Bree Witteveen/Alaska Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program)

Scientists are increasingly alarmed about the potential for more species die-offs and other adverse effects on marine mammals and seabirds if the suspected cause, a huge anomaly of warm water in the northeast Pacific Ocean, persists into summer. The warm seawater may be a catalyst for a variety of ongoing ecological incidents along the West Coast, including a breakdown in the marine food web.

Biologists and ecologists reported on a distressing list of affected marine species at a recent two-day workshop at the University of Washington. The conference was a follow-up to a similar gathering held last May in La Jolla, California, that primarily featured climatologists. oceanographers and marine researchers.

“I just wanted to point out that ‘14 and ‘15 have been two of the warmest years on record for temperatures in coastal Alaska,” said Russell Hopcroft of the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, hinting at the potential environmental and economic impacts of the warm water anomaly that has lingered in the northeast Pacific Ocean for the last two years.

“This is fed back through the state and may even be responsible for increased wildfires in the past year,” Hopcroft said.

Out at sea, the warm water mass may be depriving fish, seabirds and seaweed of their normal food sources. Water temperatures down to a depth of 300 feet have ranged from 2 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit above normal.

One theory considered by marine researchers and biologists is a distinct layer of warm water on top of cold water is creating stratification of the water column in which plankton and nitrate nutrients are prevented from rising to the surface.

“Certainly the salmon returning this year — the pinks that only go out for two years, so they were out in 2014 and 2015 — were coming back about half weight,” said Richard Dewey of Ocean Networks Canada and the University of Victoria. “The herring are half weight.”

“And so, the northeast Pacific has been pretty malnourished,” Dewey said. “I think the nourishment comes from the wind mixing of nutrients up into the Gulf of Alaska.”

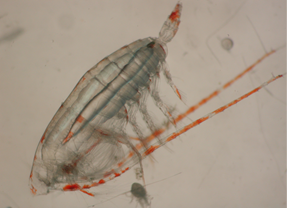

Young salmon and herring usually feed on plankton, but some plankton species such as warm water copepods have fewer lipids or less fat content than cold water species.

For the first time in his over 30-year career, Bill Peterson, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Newport Research Station in Oregon, said he saw 11 new species of warm water copepods just appear on the West Coast.

“The copepods tell us that water came from a long ways away,” Peterson said. “Where it came from, I don’t know. But it’s an issue we have to solve, I think. This water just didn’t sit there and warm up. It came from someplace different.”

As an example, an alarming spike in sea lion strandings along the California coast over the last two years may be caused, in part, by the incoming mass of warm water. Upwelling of ocean water near the coast would normally stir up cold water copepods that would be a major food source for sardines and anchovies. That upwelling was reduced dramatically or completely overwhelmed when the warm water mass moved right up to the shoreline. Sardine and anchovy populations relocated northward to find food, and sea lions may have been deprived of a major food source for themselves and their pups.

It’s possible such breakdowns in the marine food web were also the cause of the extraordinary number of whale strandings, as many as 30 were reported along Alaska’s coastline last year. There’s also the near-complete collapse of the pollock hatchling population around Kodiak Island, and this winter’s die-off of over 22,000 common murres in Alaska. Recent speculation has included starvation as a possible cause of the seabird deaths.

Scientists are also curious about whether The Blob was responsible for absence of nitrate nutrients that led to jellyfish blooms and devastation of kelp beds along the West Coast.

There was also an observed shift in the diatom population, outbreaks of paralytic shellfish poisoning, and crashes in the populations of Cassin’s auklets, Heermann’s gulls and other seabirds.

Eric Bjorkstedt, fisheries researcher at California’s Humboldt State University and the Southwest Fisheries Science Center, said they’re seeing more algae blooms which spread toxins such as demoic acid that pervade the entire food web. Bjorkstedt said one of his colleagues described it as a “wicked cauldron of nastiness.”

“That might explain why crab are so affected,” Bjorkstedt said. “This is a big deal, especially in our little neck of the woods where crab is a huge part of the economy. The fact that it’s still closed because of demoic acid is a big problem.”

Steve Fradkin, a coastal ecologist at Olympic National Park in Washington state, said they’re investigating a potential link to a disease that has infected over 22 species of sea stars all along the West Coast.

“The incidence of sea star wasting disease appears to be related to warm water temperature anomalies,” Fradkin said. “So, whenever the temperature anomaly is 1 and a half degrees or greater, we see a spike in sea star wasting disease.”

Some species may be able to tolerate such a dramatic temperature change for only a short period of time. For example, reports of California sea lion and Northern and Guadalupe fur seal strandings noticeably jumped in 2014, and then skyrocketed to unprecedented levels in 2015.

“Warm anomalies have persisted for more than two years, and it looks like the real killer was the second year,” said Art Miller, research oceanographer at Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla. “So, perhaps animals could be resilient to one bad year. But if you start stacking them up, things could start to get precipitously worse.”

Birth of The Blob, and death by El Niño?

Of course, correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation. Whale and seabird die-offs, for example, have not yet been conclusively linked to the lack of forage. Scientists want to do more research before pinning any blame on The Blob, or even going as far as suggesting that the phenomenon is a product of climate change.

Nicholas Bond, the Washington state climatologist who first highlighted the warm water anomaly and coined the nickname that evokes images of the old Steve McQueen teen horror movie, believes the genesis of The Blob was in the far western, subtropical Pacific Ocean in 2013.

“It really is a mix of different mechanisms here, and at different places and different times,” Bond said.

The mass of warm water, which grew to several thousand miles in width, became more apparent as it showed up in the northeast Pacific, the Gulf of Alaska, and then down the coast to Baja California.

Bond said they’ve all been a bit simplistic in thinking about The Blob physically moving around the northeast Pacific Ocean.

“For example last winter, very warm air coming up along the West Coast, record heat in the Pacific Northwest, and so forth,” Bond said. “It wasn’t just The Blob getting bodily moved with the mean currents.”

Bond said it’s the lack of surface fluxes, or transfer of energy through cooling, evaporation, wind and turbulence to cool the ocean. The Blob’s persistence over two years may have been partly due to a weak atmospheric pressure system called the Aleutian Low that did not generate the usual storms and necessary winds for cooling the sea surface.

“There’s a lot of north-south and east-west things here happening,” Dewey said. “I’m cautious about saying there’s one smoking gun.”

Dewey suggests that a storm in August 2012 blew out much of the summer sea ice in the Arctic. The lack of ice cover allowed for more heat retention in the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean, and less cold water eventually flowed south into the Gulf of Alaska.

“It’s not so much as where did the warm water come from,” Dewey said. “We had an absence of cooling.”

There’s evidence that an earlier version of the warm water anomaly appeared in 2004 and 2011, and some scientists believe the current Blob may be dying or already dead. But dissenters like Dewey believe there is still enough heat energy deep below the surface to keep anomaly active through this summer.

“Is it dead yet?” Dewey asked. “So, the Monty Python reference here: ‘I’m not quite dead’ to go on the cart. But, no, perhaps it’s very ill.”

Ecologists, biologists and oceanographers appear to be hoping for the worst for The Blob.

“That’s what frightens me,” Peterson said. “It’s not so much the big problems we’ve had last year and this year. But if this goes on one more year, we’re going to have a lot of dead salmon on the beach, a lot of dead sea lions, a lot of dead fur seals, a lot of dead auklets, murres. It’s just going to be a nightmare.”

One big wild card is El Niño, the phenomenon associated with equatorial warming of the Pacific Ocean. This year’s El Niño is among the top three strongest events ever recorded, and it could influence marine and atmospheric circulation patterns that stir up the water column and cool the sea surface. It could help kill The Blob, or as one scientist suggested, it could also set the scene for an oceanic tag team wrestling match in which The Blob’s impacts are later exacerbated and prolonged by El Niño along the West Coast.

Oceanographers and atmospheric scientists say there is a good chance that El Niño will probably peter out by summer, followed by the pendulum swinging the other way to equatorial cooling, or La Niña, later this year.

“So, we have to pray for La Niña,” quipped Miller after hearing hours of dire reports of possible cascading biological catastrophes.

About 100 researchers specializing in salmon ecology will participate in a three-day conference in Juneau in late March. Discussions will center on how the recent warm water conditions may affect this season’s salmon production from Alaska to California.

(Correction: Restored dropped contraction in the sentence referring to correlation vs. causation that was the result of an editing error.)