Scientists say oral histories have become a valuable resource in their research of Southeast Alaska and Northwest British Columbia indigenous peoples.

Current research that centers on the intersection of tradition and modern science were the subject of recent lectures organized by the Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau.

A multiyear research project that’s still underway centers on the excavation of Yakutat Bay area seal camps. The principal investigator is Arctic anthropologist Aron Crowell, Alaska director of Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center in Anchorage.

“Using radiocarbon analysis, we can actually date some of these events that are described in oral traditions,” Crowell said. “And, it goes the other way, too. The rich cultural content of oral tradition informs us about the kinds of things that we find, including this arrow point found on the ‘Old Town’ site on Knight Island that’s probably about 500 years old.”

Human and harbor seal migrations

Crowell showed how migrations starting in 800 A.D. of the Eyak and Ahtna people from the north and the Tlingit people from south ended up in Yakutat Bay. The people followed the harbor seal population up into the bay during the retreat of the great glaciers now known as Hubbard and Malaspina.

“Is the decline of harbor seals due to over hunting, to climate change or other factors?” Crowell asked. “The answer may lie in the archaeological and environmental record of human-seal interactions over the last centuries.”

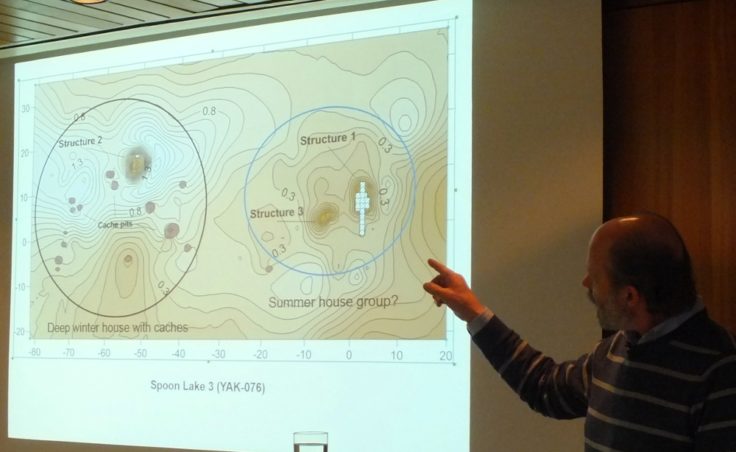

Crowell described the recent excavation of portions of house or tent structure foundations and a midden, or refuse pile, from three different seal camp sites in Yakutat Bay as part of research funded by the National Science Foundation.

Some of the recovered artifacts are as much as 800 years old and include microblades, carving chisels, knives and scrapers for processing seal skins. Other items included tiny beads, a halibut hook barb, decorative copper cone, portion of a seal hunting harpoon and evidence of seal oil rendering.

Crowell said charcoal samples can be dated with radiocarbon analysis, animal bones can reveal subsistence practices, seal bone DNA can be analyzed to show patterns of the marine mammals’ migration, and water temperatures during the Little Ice Age can be determined with stable isotope analysis of shell fragments.

“It’s a cultural archive, but it’s also a biological archive that can show us how climate and maritime animal populations have changed over time,” he said.

Crowell said the seal hunts likely ranged from several hundred seals to several thousand seals a year for commercial and subsistence uses.

“The most important product, then and now, is the blubber, which the female seals accumulate for their nursing period in the spring,” Crowell said. “And then, the oil that is rendered from the blubber, of course, is a very important food item in Yakutat. But it also found a commercial use along with whale oil for lighting and as a lubricant.”

[vimeo 112542566 w=545 h=308]

At the Glacier’s Edge: People, Seals, and History at Yakutat Bay from Kathy Dye on Vimeo.

Crowell said the seal population in Southeast Alaska at one point was enormous. It was so big that 10,000 seals were taken in 1920 without affecting the overall population. That population is now down as much as 80 percent, but Crowell doesn’t believe that hunting was the cause.

Participating in the research is Judy Ramos from Yakutat, a Ph.D. student in indigenous studies who’s also an assistant professor of Alaska Native studies and rural development at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“What is indigenous research and how is it different than Western research?” Ramos asked. “As indigenous people, we view the past which is different than the academic system. What is the indigenous view of land as a living landscape? As opposed to archaeology and geology which is the Western frame of thought, we have a different view of the past (and) a different way of thinking of history.”

Even with the recent decline in population, Ramos said the harbor seal remains a crucial part of the Yakutat culture and diet.

“In 2001, I did a subsistence survey and we harvested 262 harbor seals by 36 percent of the Native households and it was used by 78 percent of the Native households,” Ramos said.

“It’s a very important part of our subsistence resources. In the past, it was much more important because moose and deer are new to the Yakutat area.”

Clues from language and place names

Oral histories can reveal a lot about traditional seal hunting training and techniques, processing of seal and hide, and stewardship of the land and conservation practices.

Ramos also said oral history interviews provided documentation of the environmental history or migration history behind place names.

“Four of the place names are identified as Aleut or Supiak. Fourteen of the place names are identified as Eyak, and the rest of the place names are Tlingit. So, the four place names that identified as Aleut only in the outermost part of Yakutat Bay and they are at the beginning of the Hubbard Glacier recession.”

Ramos said the Eyak place names extend from the mouth of Yakutat Bay to as far as Knight Island and Humpback Creek.

“There are no more place names past this area. So, that’s about halfway up the bay,” Ramos said. “Tlingit names extend to the whole of Yakutat Bay.”

“There is definitely a correlation between the different kinds of languages that were there and the place names.”

Can crabapples map ecological ebb and flow?

Another researcher is incorporating oral histories and traditions as she focuses on the Northwest Coast people’s relationship to a common fruit, the crabapple, and whether it can be used as a keystone species for determining the effects of climate change on travel and subsistence.

Victoria Wyllie de Echeverria is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Oxford who was also a visiting scholar at the Sealaska Heritage Institute.

“Ecological keystone species is a concept that was developed quite a few years ago about a species that has a larger impact on its environment in proportion to the number of organisms that are there,” Wyllie de Echeverria said. “So, maybe it’s not the most common species, but it’s a pivotal species for other species depending on it.”

Wyllie de Echeverria is an enthnobiologist who studies interactions between people and plants, animals, and the environment. She spent the latter half of this summer and early fall doing field work in Southeast Alaska and coastal British Columbia.

Although salmon may be an example of a prime keystone species, Wyllie de Echeverria decided to focus on the Pacific crabapple. Indigenous peoples may have a specialized view of crabapples.

“From looking at the data and the literature, they were important in trade and as both a food (and) material goods as a medicine,” Wyllie de Echeverria said.

“They were also mentioned in mythologies. There are quite a few stories people would be eating crabapples at feasts. There was one story of people running away from some invaders and they threw their comb behind them and it turned into a crabapple thicket.”

The tree bark can be made into a tincture or tea, or a salve for skin irritations. The hard wood could be crafted into hooks or adze handles.

As many as 37 indigenous groups from Alaska to Oregon use the crabapple in some way. Just one species may be recognized by botanists, but indigenous groups have identified at least five separate varieties based on their location, or variations in appearance of the tree and fruit.

[vimeo 106539955 w=545 h=308]

Climate change and its effect on Native cultures from Kathy Dye on Vimeo.

Wyllie de Echeverria is trying to determine the cultural significance of crabapples while using Western science to determine the botanical and ecological characteristics of the different varieties.

She also hopes to determine how things like climate change, logging and development affect the people’s harvesting and processing of their food.

The weekly luncheon lectures in Juneau were organized by the Sealaska Heritage Institute, a non-profit organization devoted to promoting cultural and educational programs for the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian people.