A water treatment plant at the Tulsequah Chief Mine project in British Columbia has been shut down.

Mine owners Chieftain Metals shut off the plant on June 22nd. The company says it cannot continue spending money on water treatment without any mine income.

As Rosemarie Alexander reports, Acid Rock Drainage downstream of the mine has long been a concern to Alaskans, though a recent study shows metals concentration remains insignificant in some Taku River fish.

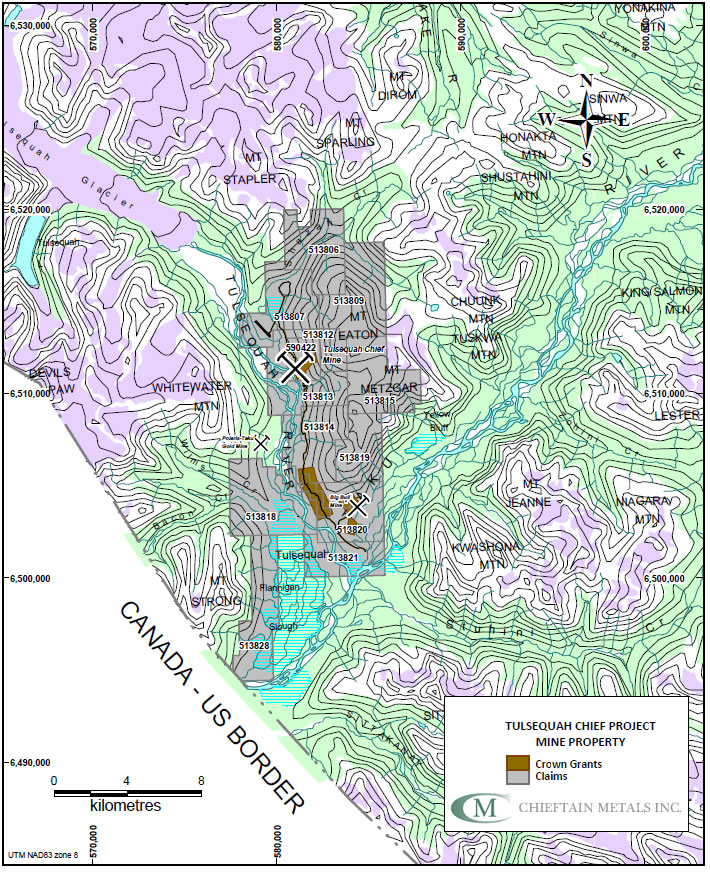

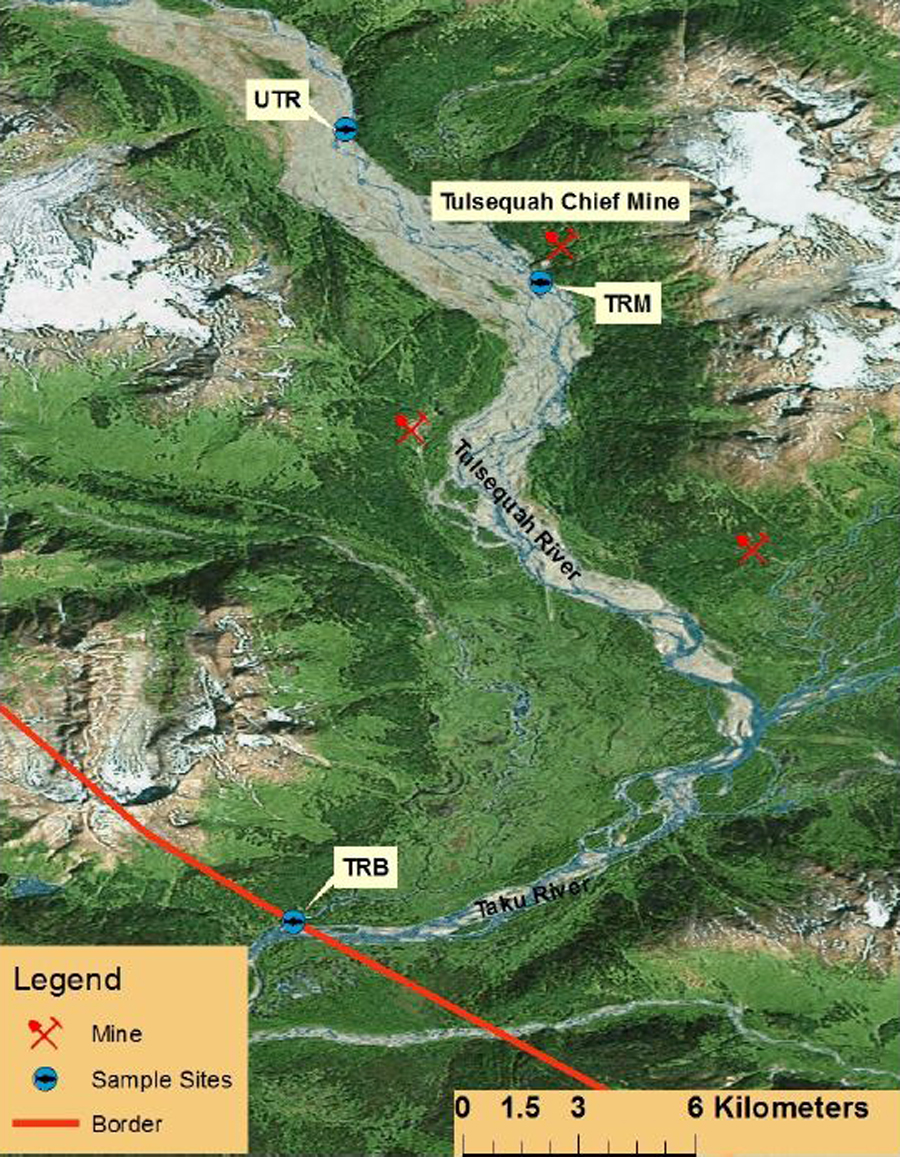

Cominco was the last company to mine the old Tulsequah Chief, closing it in 1957. The mine was never properly shut down and for 60 years acidic water has been leaching into the Tulsequah River. The Tulsequah flows into the Taku River, considered Southeast Alaska’s most abundant salmon producer.

Canadian company Chieftain Metals, Inc. purchased the property two years ago from Redfern Resources. With it, Chieftain acquired Redfern’s permits and the requirement that it would have to clean up the Acid Rock Drainage.

In December, the company started operating what’s called an Interim Water Treatment Plant – interim, because “a permanent solution is the complete development of the mine,” says Chieftain President and CEO Victor Wyprsky. And when the mine is all played out, he says there will be no acidic drainage if it is properly shutdown and “all sealed up.”

Early in June the company notified Environment Canada and B.C. Ministry of Environment of its plan to stop the water treatment for an unspecified period of time. Treatment plant costs had ballooned and to date the company has spent about $9 million on construction and operation.

As Wyprysky puts it, “no company in the world would be treating water without a mine.”

He likens it to paying a mortgage without the benefit of owning a house.

In 60 years, Chieftain is the only company to attempt to treat the Acid Rock Drainage from the Tulsequah.

Alaska Large Mine Coordinator Kyle Moselle says committing to and constructing a Water Treatment Plant prior to mine development is unique.

“The Interim Water Treatment plant was constructed to address the legacy ARD, the acid rock drainage from past mining. So that’s really unique,” Moselle says. “They’re not generating income or profit from development of the mine yet. I can’t think of a situation that mirrors that here in Alaska.”

With the shutdown of the treatment plant, Chieftain is now in violation of its Environmental Management Act permit from the B.C. government.

But when the plant was operating, the discharge into the Tulsequah River “met permit water quality concentrations,” according to Suntanu Dalal, of the B.C. Ministry of Environment. Dalal says the government has required the company to develop an action plan to get back into compliance. It’s unclear how long that will take.

The international conservation group Rivers Without Borders believes Chieftain’s decision to shut down the Water Treatment Plant indicates the Tulsequah project is not financially feasible.

Spokesman Chris Zimmer wants the state of Alaska to take the lead and work with U.S. and Canadian agencies to solve the acid drainage problem.

“I’d like to see some cross-border cooperation to clean this up. I mean this is the most productive salmon river in the region. There’s a lot of jobs dependent on it, so what I’d like to see is Alaska step up and go to B.C. and say ‘alright, what are we going to do to clean this up,’ because clearly we can’t depend on the company,” Zimmer says.

Study: Low metals concentration in Taku River fish

Six months before Chieftain started the treatment plant, the state of Alaska collaborated with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian scientists to measure the impact of Acid Rock Drainage on Tulsequah and Taku River water quality. It was the first metals testing on the U.S. side of the Taku River.

Fish and Game habitat biologist Joe Hitselberger says they captured juvenile Dolly Varden char at two sites on the Tulsequah and one on the Taku River, “well above the Acid Rock Drainage site on the Tulsequah, at the discharge site, and then on the Taku River right at the border.”

Southeast Alaska fishermen and environmental groups have long expected the worst. In fact, the Fish and Game study was precipitated by Alaska fishing organizations who concerned that drainage from the old mine 37 miles east of Juneau is threatening potential salmon harvests.

But Hitselberger says they did not find high metal concentrations in the fish.

“There was no significant difference between the fish we tested at the discharge site and the fish we tested on the Taku,” Hitselberger says. “From the metals that we looked at, the values that we got were lower than what we see at other sites in Southeast and lower than EPA criteria.”

It was a small study and Hitselberger says it would be good to gather years of data like Fish and Game has from other Alaska mining sites. But he says the results don’t indicate a need to immediately keep testing.

Meanwhile, the multi-metal Tulsequah mine is about four years from opening. Chieftain CEO Wyprysky says the feasibility study continues to show a viable project. He says it’s a matter of fine tuning the economics so it is more attractive to investors.

And, Wyprsysky says, there will be no barging up the Taku River this summer.