One of the biggest challenges for distributing the COVID-19 vaccine from drug companies Pfizer and BioNTech is keeping it cold.

But Dr. Ellen Hodges, contending with sub-zero temperatures on a remote Southwest Alaska airport tarmac last month, had the opposite problem as she prepared to vaccinate frontline health-care workers.

“It became immediately apparent that the vaccine was going to freeze in the metal part of the needle,” she said. “It was just kind of wild.”

Distributing the COVID-19 vaccine is hard enough on the road system. But the obstacles in rural Alaska are on another level.

Dozens of remote villages lack hospitals and road connections, and ultracold freezers are essentially nonexistent.

Those problems, however, have not thwarted the vaccine’s delivery. Instead, tribal health care providers have mobilized a massive effort that’s delivering thousands of doses to remote parts of the state.

Vials have been airlifted to villages by a fleet of chartered planes. Others were driven through choppy seas on a water taxi. And in a nod to the serum run that delivered lifesaving diphtheria treatment to Nome a century ago, some of the clinicians giving shots in rural Alaska were even shuttled around villages on sleds, pulled behind snowmachines.

“We have these deep stories of Alaska adventure that are related to public health,” said Dr. Tom Hennessy, an infectious disease epidemiologist at University of Alaska Anchorage. “And here’s another one playing out right before our eyes.”

On windy Kachemak Bay last month, Curt Jackson used his 32-foot aluminum landing craft, the Orca, to ferry nurses and a load of vaccine to the village of Seldovia through heavy seas and a huge tide.

“It was definitely kind of creeping along on eggshells as we’re slamming through these waves, trying to be as careful as possible, knowing there’s this super special cargo on board,” Jackson said in a phone interview. “It’s been a rough year, like, I’m not going to lie — I got choked up realizing this was like this first little step towards victory.”

In Northwest Alaska, meanwhile, Dr. Katrine Bengaard and her colleagues flew into villages on bush planes, and were picked up at the airport by residents on snowmachines who pulled them into town by sled.

“Our job was to keep ourselves, as well as all of our luggage, in the sled as we bounced along through the snow,” Bengaard said.

She and her team performed many of their vaccinations at village clinics. But for a few elders who couldn’t make it, they paid home visits to deliver shots.

One went to a 92-year-old woman whom Bengaard said grew up fearing a pandemic after her parents lived through the 1918 flu, which decimated Alaska Native villages.

Hodges, the doctor with the frozen needle, is chief of staff at Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corp., Southwest Alaska’s tribal health provider. She helped plan airborne vaccine distribution to some three dozen villages.

The effort was branded Operation Togo, a reference to one of the sled dogs that helped carry essential diphtheria serum to Nome during a 1925 outbreak.

Hodges said she asked to be on one of the first flights because she was thrilled to bring protection to villages’ frontline health aides, who have been at the “tip of the spear” during a pandemic that’s hit the region hard.

“I could hardly sleep the night before we went out,” Hodges said. “I was so excited.”

Before Hodges reached each village, YKHC made sure everyone eligible to be vaccinated was there to meet her plane on the tarmac.

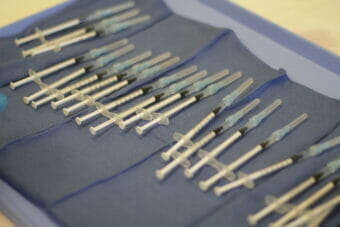

Patients came on their snowmachines and four-wheelers, sometimes in a truck. After getting their shots, they’d wait 20 minutes to make sure they didn’t suffer allergic reactions. Then the vaccinators would fly to the next village.

Hodges flew with the Pfizer vaccine in her lap for safekeeping. She solved the problem of the vaccine freezing by keeping doses tucked in her shirt until just before injecting them.

“Once we got that sorted out, it was pretty great,” Hodges said. “A lot of us felt the importance of it — of making sure we could get our health aides protected against this horrible, unpredictable disease.”

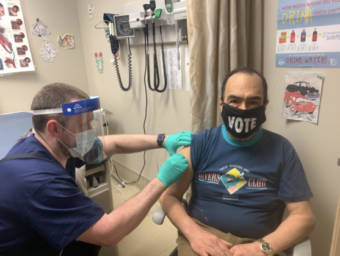

One Alaska Native elder who received a plane-delivered vaccine was state Sen. Donny Olson, 67, who lives in the remote Western Alaska village of Golovin.

Olson is Iñupiaq and a father of six, including two young twins. He’s also a pilot: He has a radio at home tuned to air traffic so he can listen as planes approach.

When Olson heard the plane carrying the vaccine call in its approach, he said, “you could breathe a little easier that they’re here, that bad weather’s not going to stop them from coming.”

“And when they landed, and I got the steel treatment in the shoulder,” he said, “That was a great relief for us, as a whole family.”