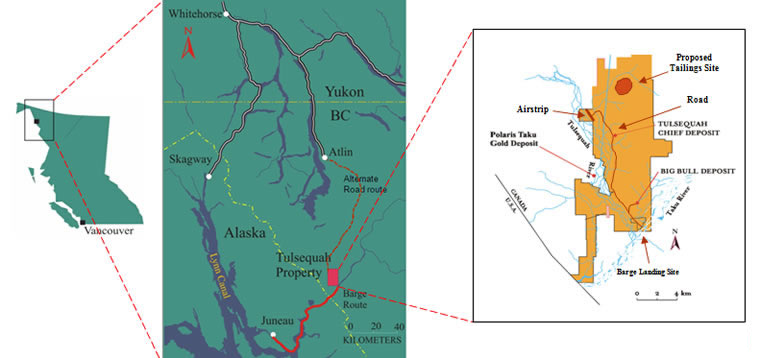

British Columbia environmental officials have approved a new route to the Tulsequah Chief Mine that avoids several traditional Native use areas and eliminates the need for Taku River barging.

A Canadian company hopes to re-open the old mine by 2015.

The Tulsequah Mine has long been a concern to Juneau because of its connection to the Taku River.

The Taku River Tlingit First Nation has steadfastly opposed a road from Atlin to the mine located near the confluence of the Tulsequah and Taku Rivers. The new route, however, grew out of discussions last year between mine owner Chieftain Metals and the tribe.

Garry Alexander is Project Director for the Environmental Assessment Office for B.C. Ministry of Environment. He said the fact the two sides worked together was important to the approval process.

[quote]“The proponent, in this case, Chieftain Metals, has an existing approval under the Environmental Assessment Act, as well as a permit to actually build the road. Now on the basis that this wasn’t the alternative that the First Nation wanted, the proponent worked with the First Nation last year to come up with an alternative route that would better meet the needs of the First Nation and the proponent,” Alexander said.[/quote]The new route is also within the Atlin Taku Land Use Plan, agreed to in 2011 by the First Nation and British Columbia government.

The plan came after years of litigation, including a lawsuit over the original permit for a mine access road permit.

When Chieftain Metals purchased the property two years ago, company officials knew the route was contentious, but maintained a road would be the only way to attract mine investors; especially since barging up the Taku River is so uncertain.

The Taku River watershed agreement presented an opportunity for Chieftain and the First Nation to negotiate a better route. Keith Boyle is Chief Operating Officer for Chieftain Metals.

“They signed a land use plan and said, ‘You know what, find an alternate route within this particular area if you want access to the Tulsequah valley’ (I’m simplifying it). So that’s the work we did all last year to actually come up with that route to avoid those contentious issues and stayed within that strategic access area,” Boyle said.

In an interview just after the company applied for the new route last spring, Boyle said it would be better for both the First Nation and Chieftain.

[quote]“It avoids the Mackinaw trail, the heritage trail that the TRT has said has always been the biggest contention around that road. And the other thing too, is actually avoids what they call the Blue Canyon area, which is the area where there is a lot of moose and caribou,” Boyle said.[/quote]The EAO’s Alexander said the prospect of less impact on habitat for grizzly bear, caribou and moose — the majority of wildlife species in the area — was a selling point for the new route. He also said it avoids a lot of potential impact to fish habitat.

“There are significantly fewer bridge crossings on the amendment then there are on the approved route,” Alexander said. “It’s quite a significant change in the number of crossings alone.”

According to Chieftain, the approved route is shorter and will reduce construction costs. It will connect with the B.C. road network at the end of Warm Bay Road, south of Atlin.

While the Taku River Tlingit First Nation worked with Chieftain on the road realignment — and was part of a government-led Tulsequah Mine working group – the tribe pulled out of discussions in July, when the company shut down a plant that was treating acid rock drainage from the mine.

At the time, the group said Chieftain had breached commitments made to the tribe.

The company said it needed to improve treatment plant operations as well as raise money to run it. The old mine has been discharging acidic water since former owner Cominco stopped mining in 1957. Chieftain Metals’ federal and provincial environmental permits require the drainage be cleaned up.

Since the B.C. government approved the new access route, First Nation leaders have had no comment. Calls to tribal leaders have not been returned.

While Southeast Alaskans should be relieved at the prospect of a road instead of barging materials and ore up and down the Taku River, transportation is just one aspect of the proposed mine.

The international group Rivers without Borders may be the most vocal mine opponent. Spokesman Chris Zimmer said the access road would provide a foot in the door for more industrialization.

[quote]“You know the road versus the barge, they have different impacts. I think the biggest worry for the road is once you put in a road like this you’re likely to see additional spin off industrial development,” Zimmer said.[/quote]Zimmer believes both transportation routes would be a problem for the Taku River watershed.

The river flows from British Columbia into Alaska waters about 10 miles south of Juneau. The Taku River is considered Southeast Alaska’s most prolific salmon producer.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.