Ninety-three students dropped out of Juneau high schools in the last school year. Statewide, more than 2,830 students quit school for one reason or another.

Unless they go back and complete their high school education, their future will likely be far less bright than their former classmates.

KTOO News today begins a series on the impact of dropping out of high school, the reasons why some youth choose to leave school, and programs to reverse their course.

We’ll take a look at some of the social and economic impacts of dropping out of high school.

Talk about a gloomy future

“There’s certainly very strong evidence that high school dropouts have a shorter life span, are much more likely to be incarcerated, significantly more health problems,” Kelly Tonsmeire says.

After all, says Tonsmeire, director of the Alaska Staff Development Network, our world is rapidly changing…

“You know the picture is really, really bleak for kids without a high school education in this new global world we live in,” she says.

The Alaska Staff Development Network is dedicated to improving student achievement statewide, through professional development programs for local districts.

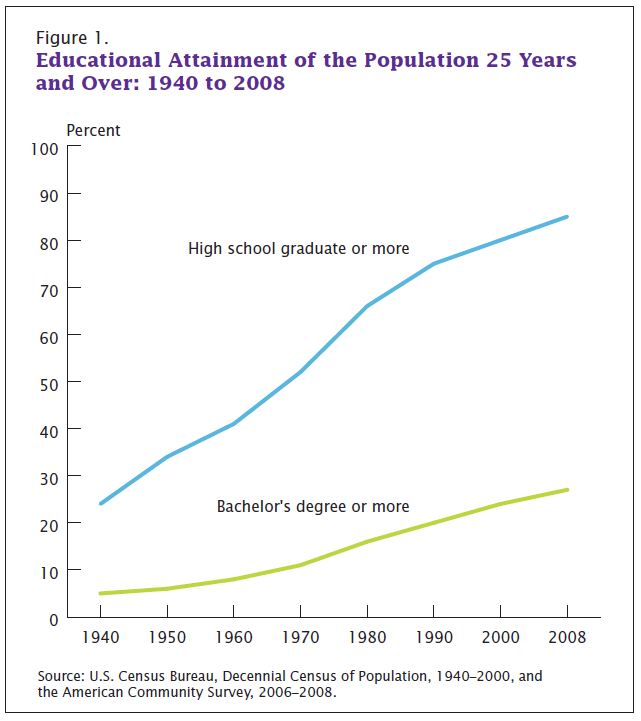

Consider this: In 1940, less than a quarter of Americans over the age of 25 had a high school diploma. By 2008, that had risen to 85 percent, and nearly 28 percent of that group had at least a bachelor’s degree, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Consider this: In 1940, less than a quarter of Americans over the age of 25 had a high school diploma. By 2008, that had risen to 85 percent, and nearly 28 percent of that group had at least a bachelor’s degree, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But people still drop out of school and communities across the country face economic and social problems related to low education attainment.

The Census Bureau estimates the median income for dropouts aged 25 to 64 at just under $11,000 a year. A high school graduate can make almost twice that.

In Alaska, however, wages tend to be higher. State labor economist Dan Robinson says the difference in earnings is significant between jobs that don’t require a diploma and those that do.

“The openings that require less than high school pay about $29,000 a year. Just moving into that next category, the openings that require a high school diploma or more and the earnings go up to $47,000 dollars,” Robinson says.

The National Center for Education Statistics indicates that students from low-income families have a dropout rate of 10 percent, while the rate is about half that for students from middle income families and far less for those in upper income brackets.

Money troubles lead to legal trouble

Poverty also leads to greater reliance on welfare, Medicaid and Medicare, and higher rates of incarceration. The Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that nearly 31 percent of those convicted of crimes in the U.S. had not finished high school. The rates were lower – though not dramatically — for inmates who had a diploma, and far less for those who had some vocational or college training.

The statistics are hard to collect; not all states require prisoners report their educational level.

The Alaska Department of Corrections does not, but a recent sample of 10 percent of offenders, about 650 inmates, indicates that more than half (59 percent) had completed the 12th grade. Eighth grade was the average education of those without a diploma.

State prisons offer adult basic education that lead to a GED. Deputy Corrections Commissioner Carmen Gutierrez says it’s popular among the general inmate population.

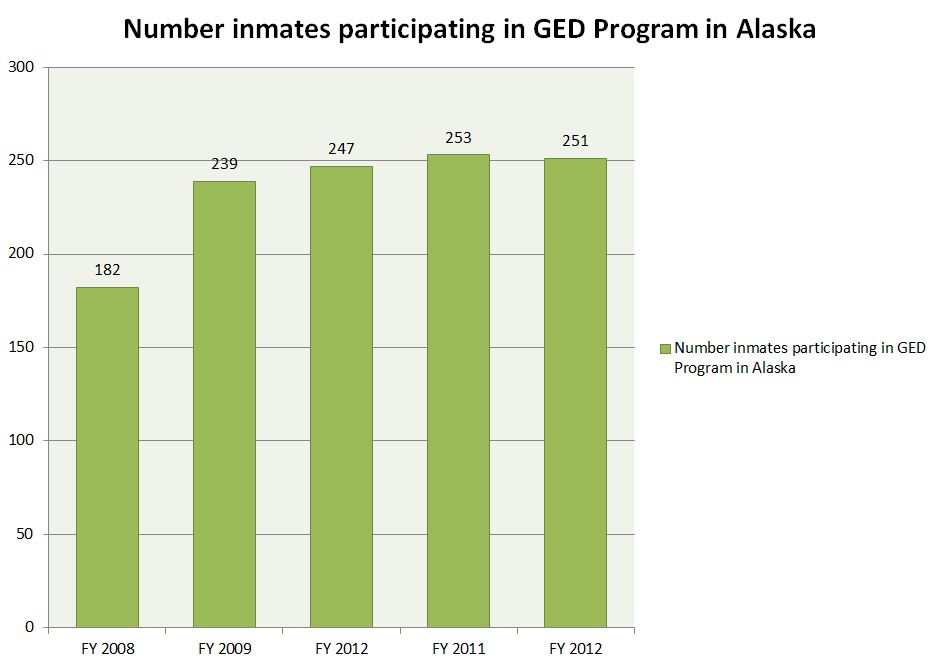

“Last year, in fiscal year 2012, we had 251 inmates receive their General Education Diploma and that number has consistently been going up since 2007,” Gutierrez says.

That year 182 inmates completed their GED. Gutierrez says the program is limited by the number of education coordinators statewide. A smaller program run through the Anchorage School District offers 32 youthful offenders the opportunity to earn a high school diploma.

The prison system also has vocational and college courses. Thirty-four year old Tisha Megus has been in Hiland Mountain Correctional Center for the last four years. She’s taken one college class and for the last two years has been enrolled in a construction course.

She does have a high school diploma, and without it she would not have been able to take the construction classes, which have evolved into an apprenticeship.

“Without this I wouldn’t have the apprenticeship. I get out in November so that’s going to carry through once I get out, so I can do the apprenticeship once I get out also,” Megus says.

But many of the 435 inmates at Alaska’s women’s prison will not have such opportunity unless they get their GED.

“I would imagine it would be extremely hard, especially getting out and having no education to back me up with, or no money to go back to school with. I’m pretty thankful for everything that they have here,” Megus says.

Rural Complications

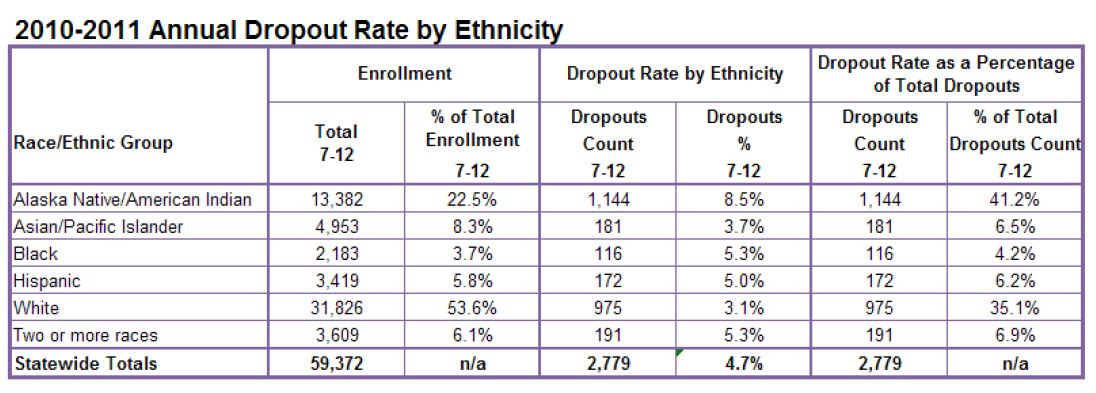

Some of the highest drop-out rates are found in Alaska’s rural villages, where the population is primarily Native.

Carl White is a former elementary school principal, and now works in the Bering Strait School District truancy office.

“In our region, the Northwest Arctic as well as the Norton Sound region, we’re number one in suicide for kids between 15 and 25, and much of dropout prevention and suicide prevention intermingle,” White says.

He says dropouts are usually treated as a problem after the fact, but risk factors begin early in a child’s life. According to White, students have a greater chance of dropping out if they are behind in reading or math, have poor attendance, or have been suspended.

At risk in Juneau

In the next part of our series we take a look at risk factors through the eyes of Juneau educators, who are trying to help kids stay in school.

Find out more about the American Graduate Program, find links and hear interviews with Juneau students and educators here.

Part 2 – For many students, an unsteady home life puts education out of reach

Part 3 – At risk students find a second chance in alternative programs