Federal scientists have launched a coordinated investigation to find the cause of this summer’s mysterious die-off of whales in the Gulf of Alaska, and they want the public’s help spotting and reporting stranded whales.

Thirty large dead whales have been observed floating or washed ashore in coastal Alaska since May. That’s over three times the average for Alaska waters.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s declaration Thursday of the whale die-offs as an unusual mortality event allows federal, state and tribal biologists to develop a coordinated response and investigation plan, and allows more access to financial, technical and logistical resources. There have been three such events declared for unusual marine mammal or whale deaths in Alaska in the last 15 years. Over 60 have been declared nationwide.

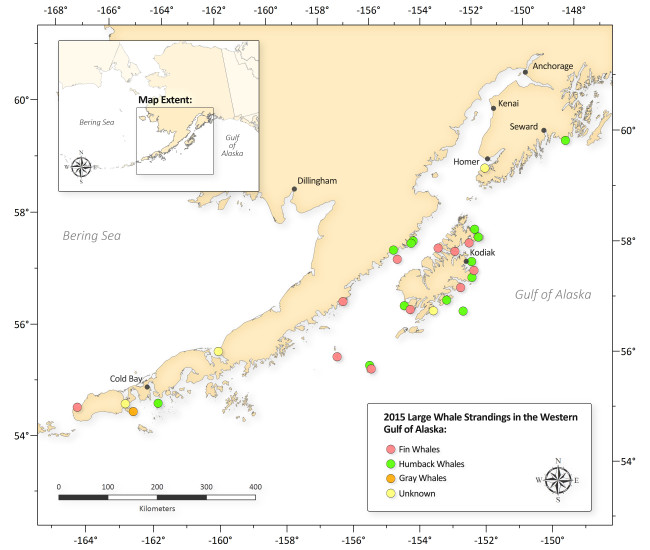

Eleven fin whales, 14 humpbacks, one gray whale and four unidentified whales have been observed stranded along the Gulf of Alaska coastline from Seward down to just past Cold Bay. Nearly half of the stranded whales were spotted just in the Kodiak Island area. It’s unknown if the increased mortality is caused by disease or a biotoxin from recent algae blooms.

Aleria Jensen with the NOAA Fisheries Stranding Network says it’s important that fishermen, boaters and beachcombers report a dead or live distressed whale as soon as possible. Contact a local stranding coordinator, the Marine Mammal Stranding Network Hotline at 877-925-7773 or the U.S. Coast Guard through VHF channel 16.

“We caution the public not to approach any animals that are sighted, or touch or handle in any way, or intervene,” Jensen says. “Most important thing is to report. Also, keep pets away from any animals that are sighted to avoid the risk of any transmission of harmful agents.”

Biologists have only been able to do a limited necropsy on one of the 30 whales so far. It may be a challenge, if not impossible, for biologists to access some of the stranding sites because of rugged geography. Bears or other predators feasting on a carcass may also make it unsafe, and high tides may carry beached carcasses away.

“One of the issues here is that a lot of these carcasses are seen floating and it might be someone who’s not very versed to determine whether a carcass is fresh or not,” says Kate Savage of NOAA Fisheries in Juneau. Savage says it’s important to sample the whale tissue, fat, eye liquid, bile, feces and urine as soon as possible.

“The condition of the carcass is paramount in taking samples,” Savage says. “And the fresher, the better. Once the tissue starts to degrade, the quality of the samples we can take and also the realm of samples we can take starts to decrease. From what I understand, the level of toxin that you would expect to find would also decrease as the carcass degrades.”

Savage and Jensen were part of a panel of American and Canadian scientists which fielded questions from the media Thursday about the investigation.

Paul Cottrell, Pacific marine mammal coordinator with the Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans, says they’ve observed four humpbacks, a fin whale and a sperm whale that were stranded on the central and northern British Columbia coast. With the exception of the fin whale in May, all of the other strandings happened earlier this month.

“Most recently, we had a sperm whale off the west coast of Haida Gwaii, Graham Island, which is again like we see in Southeast Alaska. It’s a fairly isolated area,” Cottrell says. “It’s a carcass that was observed quite a while after it hit land because it was so isolated. So, it’s fairly decomposed.”

Results from two British Columbia whale necropsies are due back in a few weeks.

Teri Rowles, NOAA Fisheries lead marine mammal scientist and National Marine Mammal Stranding Network coordinator in Maryland, says the higher whale deaths appear limited to the far northeastern Pacific Ocean.

“In comparison to what is happening on west coast of the U.S., large whale strandings are not increased in the same time frame as they are increased locally in the western Gulf of Alaska,” Rowles says. “So, this is not a coast-wide event at this point.”

One leading theory is the whale deaths are due to biotoxins from algae blooms caused by this summer’s abnormally warm sea surface temperatures, but there’s no conclusive evidence yet. Some form of an infectious disease or a virus is also a possibility. But the panel said flatly that there is no evidence the whale mortality is due to recent military exercises in the Gulf of Alaska, and they referred reporters to contact a military spokesman on that issue.

Coming up with any answer as to the potential cause of death of the 30 whales may take months, if not years.