Alaska’s 20 native languages are a generation away from disappearing. But a new effort is adding technology to the list of tools for saving the languages.

The Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks has joined Google in the Endangered Languages Project, a worldwide effort to collaborate on a website where users will find comprehensive information on endangered languages.

According to Google, more than 3,000 languages are in danger of disappearing. That’s roughly half of all languages in the world.

The site is designed to function as a social network, with users uploading speaking samples and videos, and interacting with each other. The project is encouraging speakers and language experts to share best practices for each language.

“It’s a great way to bring attention to the plight of native languages,” said Rosita Worl, president of Sealaska Heritage Institute. The institute is the cultural and educational foundation of Sealaska Corp., the Alaska Native corporation for people of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian descent. Worl is Tlingit.

“Our language may never be spoken the way it once was, but the voices of our ancestors are not going to disappear,” Worl said.

The website will create an opportunity for Alaska Native communities to add language documentation to the site as well as comment on samples and documents uploaded by other users.

UAF linguistics professor Gary Holton is Director of the Alaska Native Language Archive which is part of the Alaska Native Language Center.

“So much language information is not housed in archives. It’s in minds and in shoe boxes of old recordings and in communities,” Holton said.

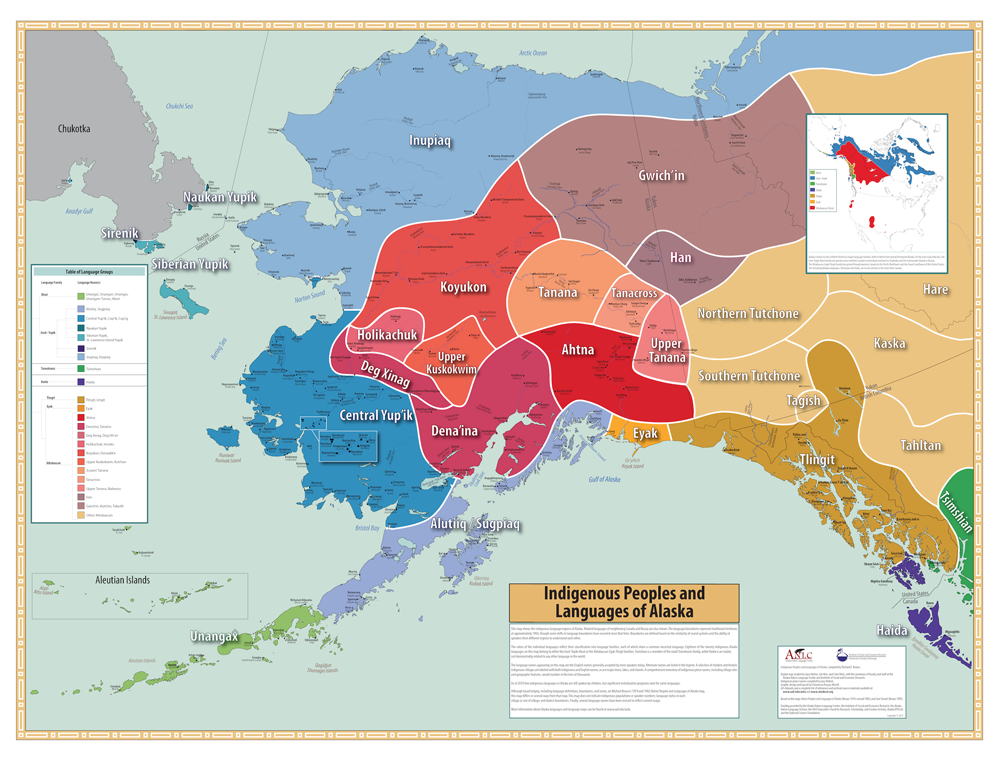

The last speaker of Eyak, the Native group of the Copper River Delta region, passed away in 2008. Marie Smith Jones worked with the Alaska Native Language Center to preserve her language.

Other languages range from having one or two speakers to thousands of speakers, like Central Yup’ik.

“It’s hard to count the number of speakers,” Holton said.

People move away or marry into different communities and while they may be able to speak the language, they don’t identify themselves as speakers of that language.

The goal of the Endangered Languages Project is to add real-time interactivity to the work that many language archives are doing. Archives already make materials available online and for download. This new project will be the first time people can upload their own materials and annotate the documentation of others.

Holton reminds people that the technology itself will not do the work.

“What this project provides is a platform. This is not a magic bullet for saving languages,” Holton said. “This is only as good as what people put into it.”

The center is encouraging local grass-roots efforts to contribute to the site. It’s also incorporating current programs, workshops and culture camps to contribute to the website.

“Documenting native languages is very different from restoring them,” Worl said. She emphasizes the need for immersive learning experiences that teaches the language by using it in school and home, rather than memorization.

“Unfortunately, I don’t think you can consider any of the languages of Alaska safe,” Holton said. “Most are in a situation of being one generation away from being lost. It’s only by sharing language and using language that we can save it.”