Researchers expect that salmon productivity could shift in Southeast Alaska streams over the next seventy years as temperatures rise and rainfall increases because of climate change.

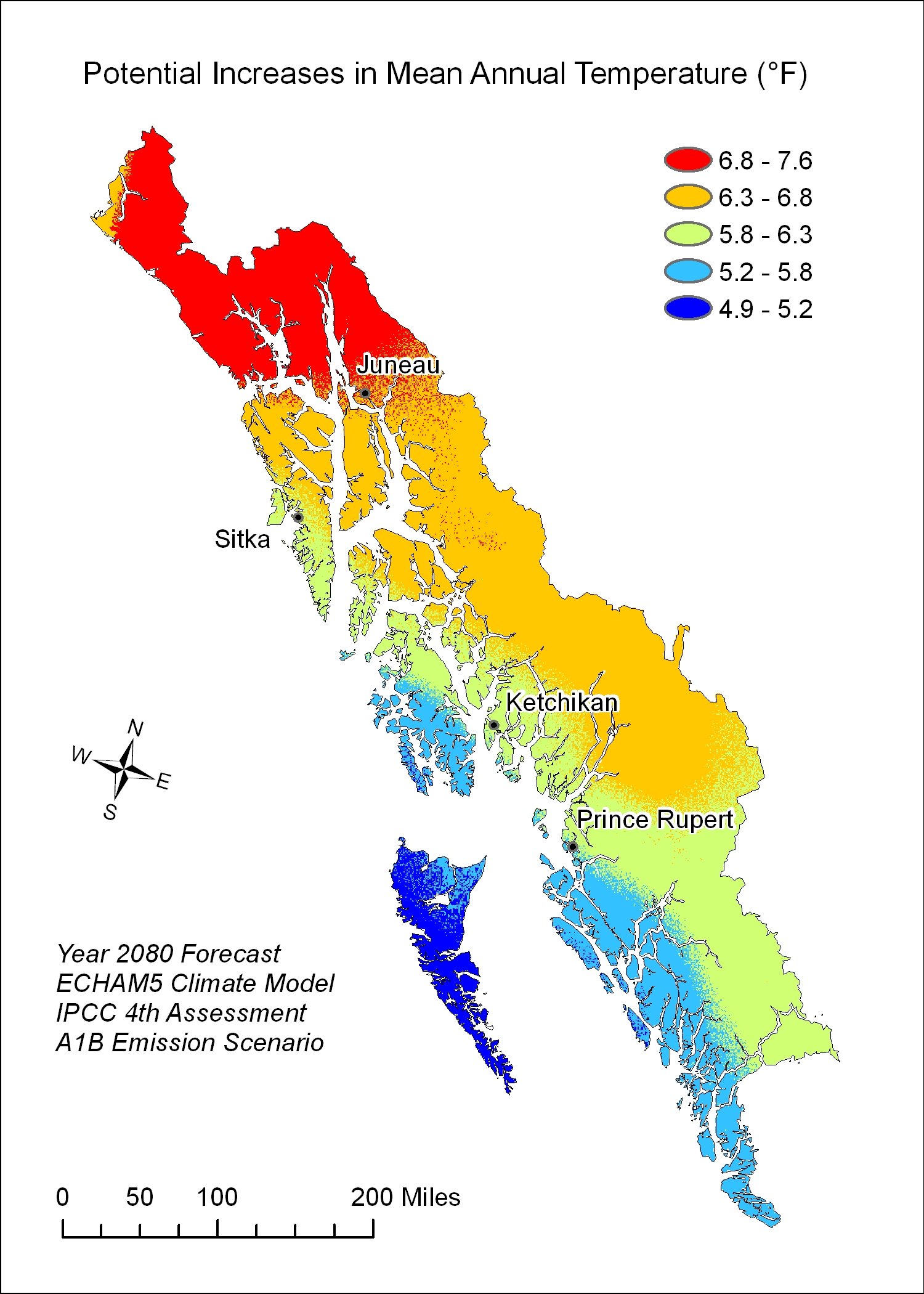

Projections suggest that the average annual temperature for Southeast Alaska and western British Columbia coast would increase 6.1 degrees to just under 44 degrees Fahrenheit in the year 2080. Precipitation in the form of rain could increase over twenty inches to a total of 145 inches, while snowfall could drop about 30% to about 30 inches a year.

“There could be some serious differences,” said Michael Goldstein, a wildlife ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service in Juneau.

Goldstein was among a group of researchers who briefed attendees on the unpublished research at the recent Southeast Alaska Watershed Symposium in Juneau. A similar presentation on the impacts of climate change was made during the recent Al-Can Summit organized by the Juneau World Affairs Council.

Goldstein said the changes in temperature and precipitation would not be uniform throughout the entire Southeast Alaska and western British Columbia area.

So, temperature and precipitation had the greatest change in the northern mainland and the least change in the southern island provinces. Precipitation as snow had the greatest change in the southern mainland and the least change in the outer coast.”

It could mean warmer and drier extended summers, and warmer and wetter winters.

By 2080, Juneau could be like Prince Rupert. Projected average of 45 degrees Fahrenheit or thereabouts is similar to the average temperature of May 2013. I was looking around the internet and Alabama has an average winter temperature of 45 degrees as well.”

The projections were presented in conjunction with separate research and modeling done by Colin Shanley, a planner and analyst with The Nature Conservancy in Juneau, in his effort to identify salmon habitat ranging from the most vulnerable to the most resilient.

This is watershed-based analysis. Not a cell-based analysis or estuary-based analysis. Basically, watershed area, monthly precipitation both present and predicted from the present climate model, same thing for monthly temperature, watershed elevation, percent lakes, and percent glaciers as well.”

Dr. Sanjay Pyare, associate professor of geography and environmental science at University of Alaska Southeast, said that climate change could play a crucial role in altering stream temperatures and episodic discharges from nearby glaciers and the ice field.

If you look at the overall discharge coming out of an area like Southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia annually compared to a place like the Mississippi River Basin, it’s actually something like two times the overall freshwater discharge. Obviously, it has a lower land mass overall. So, there’s a lot of water coming down the pipes in a place like Southeast Alaska.”

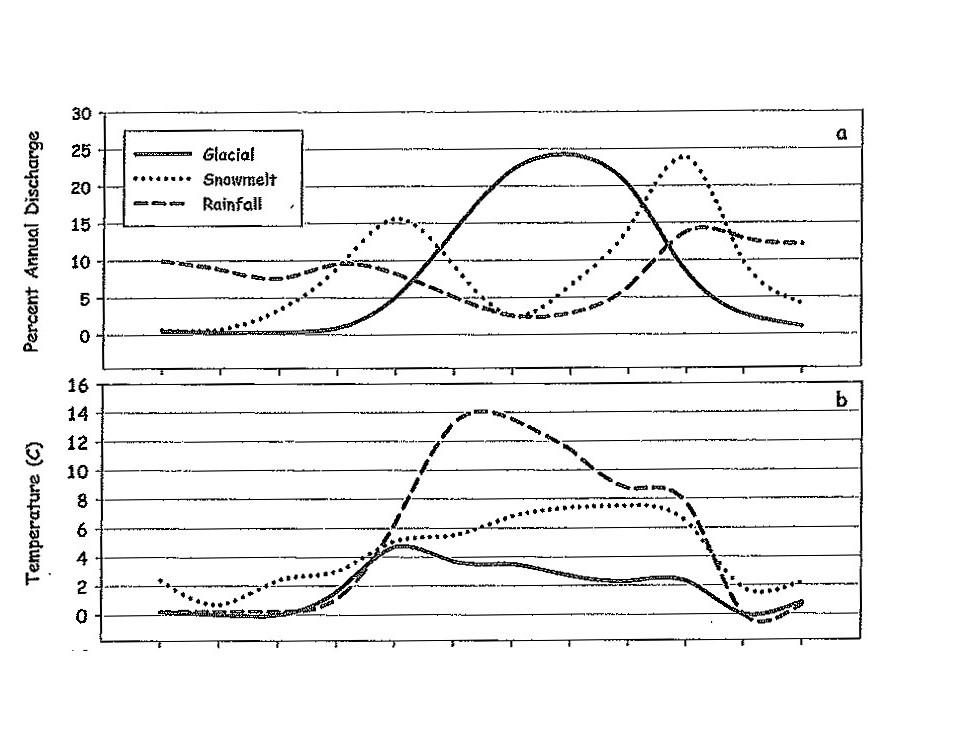

Watersheds that are predominately glacial-fed may, for example, have their peak discharge in mid-summer with colder water. Snow- or rain-fed watersheds may have two discharge peaks in the spring and early fall.

So what does all this mean for Southeast Alaska?

The research suggests that an increase in temperature and rainfall levels brought on by climate change could alter the discharge timing and raise the summer water temperature of formerly glacial-fed watersheds.

The Forest Service’s Michael Goldstein expects that alpine temperatures will eventually exceed current sub-alpine temperatures. Along with a decrease by a third of accumulated snowfall, he said that elevation of the tree line could rise by as much 600 feet, and – referring to research by others – raise the lower sub-alpine boundary by 1200 feet.

Goldstein suggests that there would not be a significant increase in the fire danger. But there may be an increase in number and severity of insects and disease.

Projected increases in temperatures could expand lowland forest habitats in the winter. Ungulates, for example, could have reduce energetic costs if there is no deep, deep snow to go through. So, there’s a lot of different implications out there. A longer growing season may increase food availability for wildlife in the spring. So, that’s on one hand. But on the other hand, we clearly understand that could be some timing issues. Right? Rusty blackbirds eating dragonflies, dragonflies coming out later, rusty blackbirds not having higher nest success because there’s no food source when the chicks are being reared.”

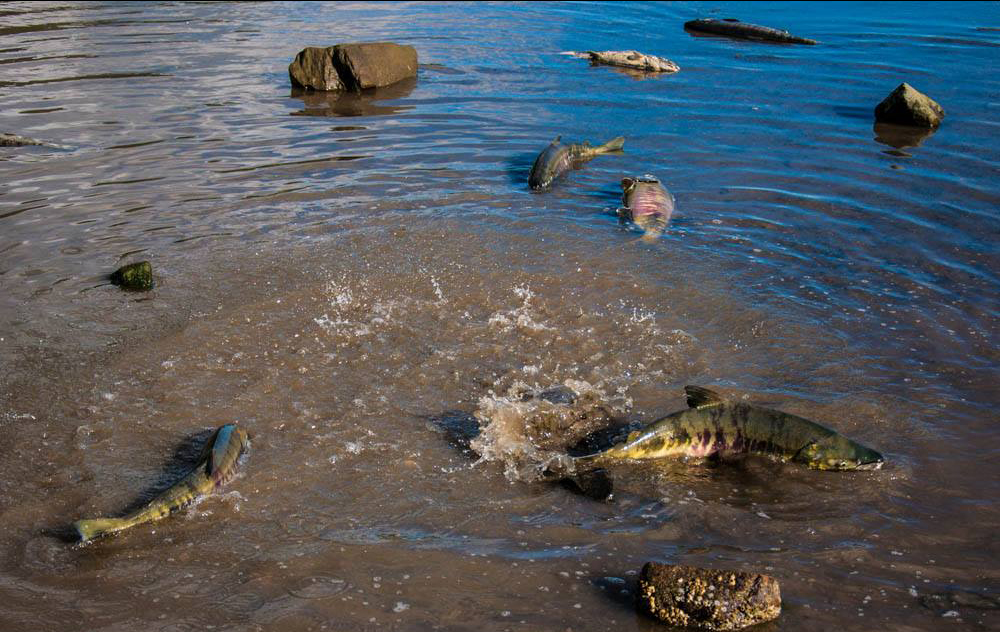

Goldstein points to other research demonstrating that Auke Creek salmon runs have already occurred two weeks earlier than runs of thirty years ago. UAS’s Dr. Sanjay Pyare said a few degree change in water temperature could alter the growth and development of salmon at various points of its life cycle.

It’s critically important, in particular, to younger stages, juvenile stages. So, we know that incubation times are well known to be inversely related to stream temperature, and stream temperature through its affects on development, accelerating or slowing down basically the size of juveniles, can impact out-migration times. So, warmer temperatures influences out-migration or can accelerate out-migration. We have some initial thinking that at a regional level the stream temperature could be pretty important in terms of adult migration. So, we started to look at watersheds that are exhibiting some evidence of run timing shifts in adults.”

The Nature Conservancy’s Colin Shanley said another big worry among fisheries biologists includes changes in discharge flows.

With this transition from snow-fed watersheds to rain-fed watersheds, we’re going to see more rain on snow events, higher flows, (and) more scouring of salmon roe. So, salmon roe getting kicked up out of the gravel before they have time to incubate.”

While some streams would ‘blink off’ as productive salmon habitat because of climate change, others could very well ‘blink on’. Steams that currently do not have any salmon runs could someday become productive with subtle changes in temperature or discharge flow.

Besides the possible implications on salmon productivity and management, the researchers acknowledge that they are only now touching the surface of potential climate change impacts in Southeast Alaska and western British Columbia. There are a variety of other implications to explore that range from municipal planning of streamside setbacks to managing hydroelectric facilities and tourism operations.