The Golden Triangle describes a mineral-rich region of northwest British Columbia. Its mines and exploration projects are in the watersheds of salmon-rich rivers that enter the ocean in or near southern Southeast Alaska.

Exploration companies say they’re finding more and higher-grade ore that could lead to new gold mines. But more drilling doesn’t necessarily mean more development.

“In the northwest corner of British Columbia lies a geologic formation known as the Stikine Terrain, which holds some of the richest gold ore bodies in the world,” begins a YouTube video by iResource Media, which covers the mining industry. “This area is so rich, in fact, that they call it the Golden Triangle.”

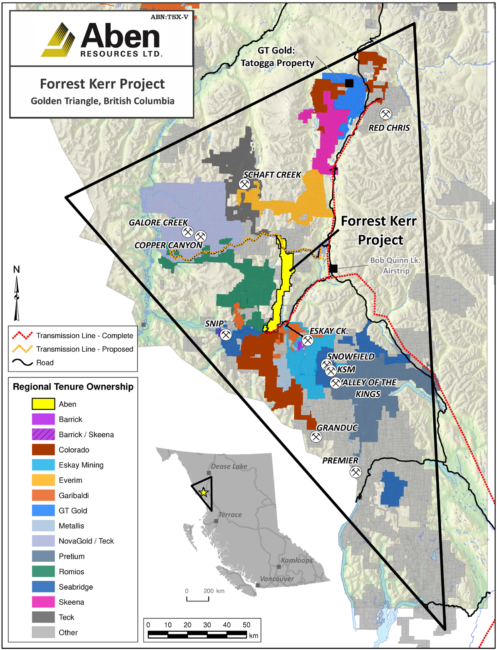

It and similar reports describe two active mines and close to a dozen exploration projects in the area. They’re upstream from the Stikine or Unuk Rivers, which flow through southern Southeast Alaska. Or they’re in the headwaters of the Naas River, which empties into the ocean just south of the Alaska border.

One of the newer drill projects is the Iskut, owned by Seabridge Gold. Spokesman Brent Murphy said the company is in its second year of exploration.

“We had some success last year where we found some evidence of gold mineralization, and now we want to go out and see if we can find the origin and source of that gold so that we can develop a potential resource,” he said.

The project includes the closed Johnny Mountain Mine. Seabridge has removed and cleaned up abandoned fuel tanks and other contamination that project left behind.

Murphy said it looks promising. But that doesn’t mean it will become a mine.

“It’s way too early to even speculate. We are just in the very early stages of exploration,” he said.

Seabridge also owns the Kerr Sulphurets Mitchell project, which it’s been pursuing since the early 2000s. In recent years it’s been granted key permits needed for construction. The company is actively seeking investors.

KSM, as it’s known, is the largest project in B.C.’s Golden Triangle. Murphy said the company has located new deposits of valuable minerals.

“What we’ve found over the last three to four years is we’re definitely hitting higher copper grades and gold grades,” he said.

Iskut and KSM are but two of the exploration projects claiming to have found valuable metals in the Golden Triangle. Calls to other companies were not returned. But all are clearly taking advantage of regional upgrades and the lucrative trend in the industry.

A key factor is the rising price of gold, which has been hovering around $1,300 per ounce. That’s more than twice the value of a dozen years ago.

Another factor is infrastructure. New pavement, hydroprojects and power lines have been developed with support from the British Columbia government. And a deep-water port has been developed at Stewart, the anchorage nearest to the Golden Triangle mines.

“There’s a lot of exploration work taking place and that kind of waxes and wanes,” said Kyle Moselle, large mine project manager for Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources.

He and a state biologist toured some of the Golden Triangle sites last fall and saw evidence of increased activity. The improved business climate is leading to more drilling, but that’s it.

“Does that mean that there’s a flood of mine projects coming? I don’t think so. I’ve never seen exploration work be an indication of actual mines being developed or proposed,” he said.

The number of projects makes it difficult for environmental, fisheries, tribal and government mine critics.

They say pollution from digging and milling could end up in transboundary rivers, threatening salmon and other fisheries.

“It’s hard to really prioritize which are the most important ones, which are the ones that might go ahead and which are the ones that could have effects down here in Alaska,” said Chris Zimmer, Alaska campaign director for Rivers Without Borders.

He’s tracked transboundary mines and exploration projects for years.

He’s encouraged by political changes in the federal and provincial governments. They continue to support development, but appear to be putting more emphasis on environmental protections. But he said those are long overdue.

“As I look at that, all that does is put us back to where we basically should have been 10 years ago. Fix the flaws in the B.C. assessment process over there. It’s definitely not a magic bullet and not the best way to address our concerns downstream,” he said.

Climate change is also making it easier to explore for gold and other rare minerals.

Warming global temperatures are melting back ice fields and glaciers in the Golden Triangle, allowing easier access to once hidden ore.