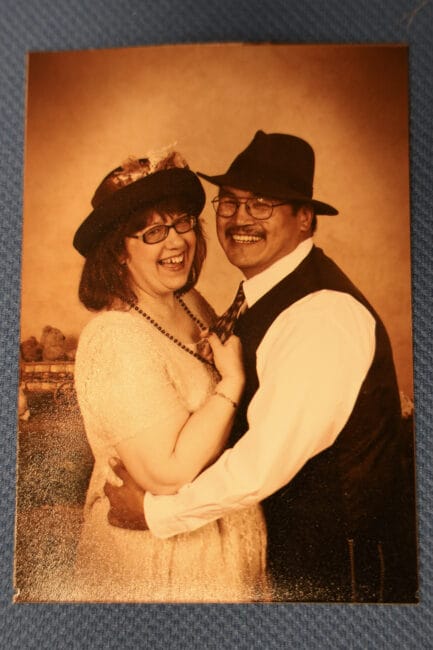

Tammy Jablonski Murphy said she had given up on the prospect of finding love before her first date with Joseph Murphy in the late 1990s.

“But he kissed me, and it was like, ‘I’ll marry you right now.’ I mean, that’s how I felt in my heart,” she said. “I thought, ‘I can see me with you for the rest of my natural life.’”

Instead, their years together were cut short.

Listen:

Joseph Murphy died of a heart attack on Aug. 14, 2015 in Juneau’s Lemon Creek Correctional Center after guards refused him care. He was there on a protective custody hold — a type of hold intended to prevent someone from harming themselves or others while intoxicated. He wasn’t charged with a crime.

Jablonski Murphy said her late husband had a heart condition, but it was treatable, and that he may not have died if he’d had access to his medications or medical care. She and Murphy’s family sued the state for wrongful death and settled out of court.

It’s been 10 years, and Jablonski Murphy is still mourning. She wants to know if the state has changed its policies to prevent deaths like this in the future.

“I want to know what’s changed,” she said. “Because if nothing has changed, I’m not laying my banner down, kid. I’m not.”

A KTOO investigation shows that the state did make some initial changes and the number of in-custody deaths decreased for a couple of years.

But those changes were undone under Gov. Mike Dunleavy. The state has seen some of its highest number of deaths in custody per year under his administration – peaking at 18 deaths in 2022.

Leading up to Joseph Murphy’s death, his widow said he had relapsed into drinking after years of sobriety. He had quit drinking after leaving military service in Iraq a decade before. She says he was becoming progressively more suicidal.

Jablonski Murphy helped him try to seek care at Bartlett Regional Hospital and other treatment facilities without success, and it culminated in the sequence of events leading to his death under a protective custody hold in prison.

“He went to treatment. He was at the hospital. They sent him to the jail,” she said. “It just kept going, and I was watching him fall through every crack you can imagine.”

Then, one night in August a few days before Jablonski Murphy’s birthday, he told her she would be better off without him. She was afraid that if she fell asleep, he would hurt himself. So, she took him to Bartlett Regional Hospital.

Staff there said he had to go to Lemon Creek Correctional Center. He wasn’t being charged with a crime. He was held on a “protective hold” intended to prevent people who are intoxicated from harming themselves or others.

Jablonski Murphy said she tried to insist the officers let Murphy take his heart medication with him, but they didn’t allow it. Instead, the officers said they would call 911 if anything happened.

Murphy died the next morning.

Investigation and aftermath

By the time Murphy died, 25 people had died in Alaska Department of Corrections facilities in the preceding years. Then-Gov. Bill Walker had already ordered an investigation of the department prior to Murphy’s death. The investigation’s findings were released in a report in November of that year, and they were scathing. The report included an analysis of how Murphy died.

The report said that video footage from the prison showed guards dismissing Murphy’s repeated calls for help. The video did not have any audio.

One staff member said he was in the bathroom when he overheard Murphy saying he needed his heart medication. Another staff member responded, telling him, “I don’t care, you could die right now and I don’t care.”

Emergency medical services were called when a different staff member found him unresponsive on the floor. By then it was too late. Murphy had died of a heart attack.

Dean Williams, who was special assistant to the Governor at the time, spearheaded the investigation.

He said the law that allows for protective custody increased the danger Murphy faced in prison.

“Mr. Murphy was not there under any criminal allegation, but under a statute that was designed to protect him,” Williams said. “And unfortunately, the statute that was designed to protect him contributed to his death.”

Williams said the staff of Lemon Creek misinterpreted the law — it says people can be held until they are sober, or up to 12 hours. Williams said the staff involved with Murphy’s death believed he had to be held for at least 12 hours, The state’s report said Murphy appeared sober in the hours leading up to his heart attack and could have been released.

Williams said staff also exhibited a blatant lack of concern for Murphy’s well-being.

“They handled Mr. Murphy in a horrible way, in a cruel and callous way,” Williams said. “The man was having a heart attack in front of everyone, and nobody called 911.”

Williams later served as DOC Commissioner from 2016 to 2018. He created an internal investigations system for Alaska’s Department of Corrections – a change to prevent more deaths like Murphy’s, he said.

“The death of Mr. Murphy shocks our conscience, and it should, right?” Williams said. “But that was not the only one.”

Williams said internal affairs units can thoroughly investigate deaths and find ways the system failed and can improve, instead of sweeping custody deaths under the rug.

“That’s why you have internal affairs,” he said. “It’s not a luxury, it’s an essential component, which is why every other state has it.”

But Alaska’s next DOC Commissioner Nancy Dahlstrom, under Gov. Dunleavy, dismantled the internal investigations unit in 2018. Legislators said the cut would save the state money. Dahlstrom could not be reached for comment.

Alaska DOC hasn’t had internal investigations since. The department’s spokesperson said there are no plans to resurrect it.

KTOO could confirm only that most states have internal affairs units. But Michele Deitch, director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab in Texas, said Williams was right — Alaska is the only state she knows of that doesn’t have internal investigation mechanisms.

Some policy documents reference internal investigations, but Department of Corrections Spokesperson Betsy Holley said the department only conducts reviews, not investigations. She said the investigations are conducted by Alaska State Troopers “ensuring neutrality and objectivity.”

In recent years, deaths in Department of Corrections custody have garnered public outcry, and multiple lawsuits from the American Civil Liberties Union.

There were 110 inmate deaths in DOC custody between 2015 and 2024. Two-thirds were reported as “natural” deaths, including Joseph Murphy’s.

Juneau’s health care safety net

While changes in the state’s corrections department were relatively short-lived, Juneau health care services have changed in ways that could reduce the chances that someone in Joseph Murphy’s condition would end up in a state corrections facility at all.

Many people in crisis may now get help before they end up in a protective custody hold at Lemon Creek. Jodie Totten is the medical director of Bartlett Regional Hospital’s emergency department. She wasn’t working at Bartlett in 2015, but she said in the several years she’s been with the hospital, she’s seen changes to the landscape of care for people suffering from mental health and substance use conditions.

Now, Totten said, Bartlett’s emergency services staff rarely sends patients to Lemon Creek Correctional Center.

“I mean, we’re always trying to avoid having to have people go to Lemon Creek,” she said. “And there are a lot of other great options in the city that I think we should all be really proud of.”

Some facilities like Rainforest Recovery, a residential substance use treatment facility at Bartlett Regional Hospital, have closed in the meantime, limiting care options.

But Juneau’s CARES teams —Community Assistance Response and Emergency Services – were formed in 2019. Those teams are staffed by medical providers and emergency responders that help provide crisis care and follow up with patients who have long-term needs.

CARES also offers a sobering center, where people can recover from intoxication under medical supervision.

With these programs, when someone is experiencing suicidal ideation, loved ones can request providers come to their home and offer support or intervention.

And the support network may not be improving just in Juneau. Across the state, the numbers of protective holds halved in 2020. The decrease only continued, from 1,301 holds in 2015, to 379 in 2024.

Murphy’s widow

Tammy Jablonski Murphy said the pain of losing her husband is still with her. She’s 66 years old, and she still works as a social worker. She helps people recovering from addiction and people reentering the community after incarceration. She said her work is a tribute to Murphy.

“If I can help one person crawl through this fractured, broken system and come out the other end and be able to claim their life back and start over – get their families back, whatever they need to do – then that honors my Joe, and that’s what I’m all about,” she said. “That’s what I’m all about.”

She doesn’t plan to retire anytime soon. And she doesn’t plan to let go of the memory of her husband, no matter how many years it’s been.