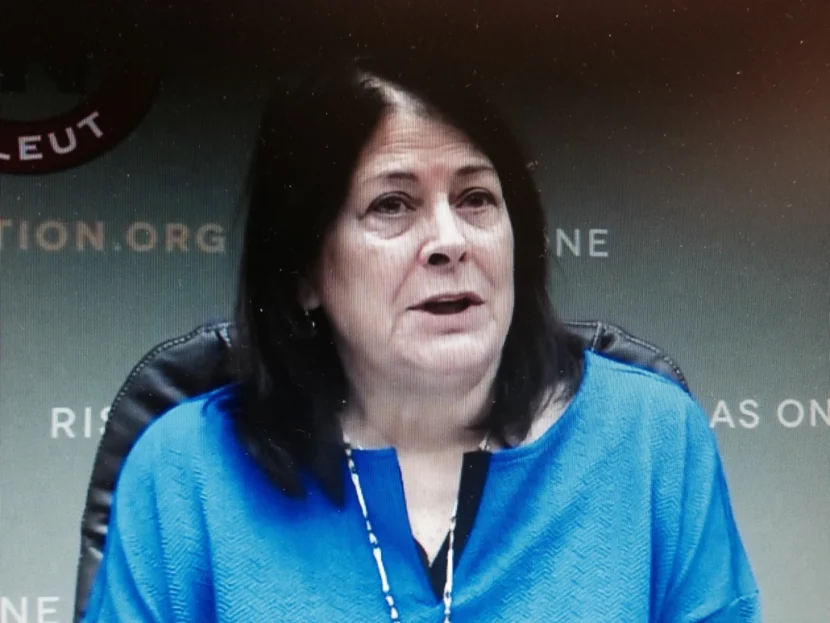

“The foundation of the Alaska Federation of Natives is our people,” said the statewide organization’s President and CEO Julie Kitka, Chugach Eskimo, after a quarterly meeting of the organization’s board held on May 15. Her comment focused on the theme of this fall’s annual AFN convention: Our Ways of Life.

It’s also perhaps a response to the predicament the organization finds itself in: a diminishing membership. AFN represents and advocates to influence policy for 158 federally recognized tribes, 141 village corporations, nine regional corporations, and 10 regional nonprofit and tribal consortiums that contract and compact to run federal and state programs. .

The National Congress of American Indians, a national tribal policy organization based in the nation’s capital, is similar to AFN in terms of trying to represent hundreds of tribes with a wide range of interests and backgrounds while maintaining membership.

What drives members to resign? What keeps them united?

Two large regional tribal entities resigned from AFN earlier this month: southeast Alaska’s tribal consortium Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, and the Interior region’s nonprofit Tanana Chiefs Conference. That comes after three for-profit Alaska Native regional corporations dropped out in the past few years.

Tanana Chiefs stated, “Over the past few years, over 40 resolutions were passed by the full board at AFN that support a subsistence way of life, but no significant action has been taken on those directives.” Tlingit and Haida said it’s in its best interests to directly advocate for its people and communities, and it has strategically built capacity to do so.

The Arctic Slope Regional Corp. withdrew its membership after delegates of AFN member organizations at the 2019 AFN convention voted to declare a “climate emergency,” overriding the Arctic corporation’s opposition. Doyon, Limited, the regional corporation for Interior Alaska, had been urging improvements to AFN’s process for addressing conflict before it resigned in 2022. The Aleut Corp. resigned last year over fisheries.

The fisheries issue came up at AFN’s 2022 convention in October. Tanana Chiefs and delegates from the southwest Aleutian Islands region got into a battle over management of an area in North Pacific waters. Tanana Chiefs believes if fishing in Area M (a management designation) were cut back, more salmon would reach the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers for subsistence users. The Aleutian delegates said closing Area M would only hurt them without benefiting other fisheries.

For both sides the argument was about putting food on the table.

When the convention voted in favor of AFN recommending to authorities that Area M fisheries be reduced, the Aleutian delegates stood up and turned their backs to the convention chair and audience.

Now two parties to that disagreement, The Aleut Corporation and Tanana Chiefs Conference, have resigned from AFN.

AFN’s first president, Emil Notti, who is Koyukon Athabascan, said AFN shouldn’t have been in that argument. The way to handle it, “would be to call the parties together, call a statewide meeting or a conference and talk about what can be done but arrive at a common solution.”

“Both sides are mad now. (Resigning) is just short sightedness on the side of these organizations,” he said.

Notti said the members who left AFN will feel, and regret, a loss of influence. He described a meeting organized by AFN and held in Washington, D.C., a few months ago. “They had five or six generals there. I think they had four Cabinet members there. They had John Podesta (White House deputy chief of staff), who has the ear of the president. They had the White House budget director. They had other influential people at this conference.”

“(The Alaska Federation of Natives) pulled it off,” Notti said, something he said smaller organizations couldn’t do. “Tlingit and Haida by itself couldn’t do it. Tanana Chiefs couldn’t do it. None of the regional corporations can get that kind of power to organize something like that. So I think that illustrates why they need to stay unified — in order to influence policy.”

“Our ancestors understood the need for a united front. AFN is a gift from your ancestors. Keep it strong,” Notti said in a statement. AFN was founded in 1966 to fight for land claims for tribes. The claims movement led to the enactment of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, which transferred nearly $1 billion and title to 44 million acres of land to for-profit corporations created under the new law.

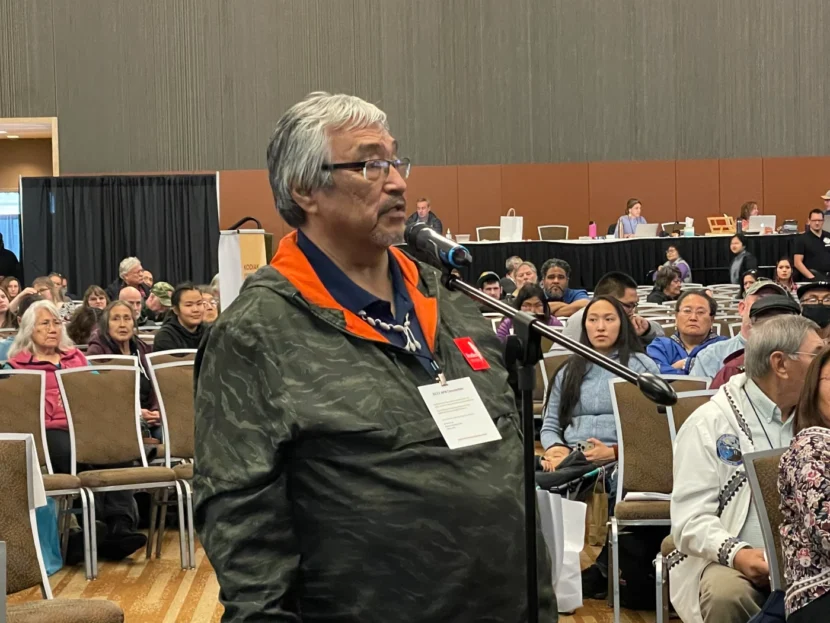

Tribal leader and long-time tribal advocate Mike Williams, who is Yup’ik, supports the tribal withdrawals. He said for decades AFN hasn’t given strong support to the priorities of tribes, especially tribal subsistence and sovereignty. Williams is chief of the Akiak Native Community and NCAI regional vice president for Alaska.

For instance, Williams has advocated that AFN support the transfer of Alaska Native corporate lands to trust status, which would provide protection from takings and strengthen self governance. “These are our lands, these are resources that we’re living with, and we’re suffering because of inaction,” Williams said.

Notti said AFN works to promote tribal interests on both subsistence and sovereignty but is limited in what it can get federal and state agencies, the state legislature, and Congress to do on those as well as many other issues.

The National Congress of American Indians was founded in 1944 to influence policy and otherwise advocate for its tribal members.

Like AFN, NCAI relies on membership dues for some of its operating costs. NCAI is the oldest, largest and most representative American Indian and Alaska Native organization in the country. Of the nation’s 574 federally recognized tribes, 40 percent are Alaska Native.

W. Ron Allen, S’Klallam Tribe, is chairman and CEO of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe located in western Washington state. He was NCAI president from 1995-1999. He also served on the board as first vice president, secretary, and treasurer, for 26 years in total. He said NCAI’s membership is down to about 150 from a norm of 200 to 300 but it fluctuates for a variety of reasons.

He said NCAI’s bylaws forbid the organization from taking sides in intertribal disputes. In the case of a tribe’s withdrawal over NCAI actions, the board would send a delegation to meet with the tribe, Allen said.

“We just encourage and we recognize and respect their position. If a tribe’s got one position, whatever it is, that is so important to them that they feel that they, in good conscience, can’t remain a member of an organization that is intended for unity, we’re disappointed, but we’re not discouraged,” Allen said.

He reminds tribes that “a singular voice is like the single twig that can break easily. But if we bond together, like a bunch of twigs together, then we can’t be broken.”

In his view, single tribes can’t win alone. “The political system that surrounds you, no matter where you are, whether you’re in Alaska or anywhere else in Indian country, the system is too big. It’s too overwhelming. It’s too complicated,” Allen said.

“It’s a multi-layered chess game, and it’s complicated because now the tribes, the tribal leadership is involved at the local level, at the state level, at the regional level, at the federal level, even at the international level. And so it’s hard for leaders now to grasp the magnitude of the game that they’re within and not realizing that they need to work together,” he said.

“No matter how good you are, no matter how much energy you have, there’s too many bases to cover and you need to cover them together.” Allen concluded, “you have to make a few mistakes before you realize this (going it alone) doesn’t work.”

For its part, AFN said it “will continue to advance and enhance the political, cultural, social, and economic voice of Alaska Natives. The board of directors remains hopeful for full membership again in the future.”

AFN said its annual convention will be held October 19-21, 2023 in Anchorage, Alaska. NCAI’s mid-year conference is June 4-8, 2023 in Prior Lake, Minnesota

The Alaska Federation of Natives did not respond to a request for comments to add to their prepared statement. The National Congress of American Indians had no comments for this story.

This story originally appeared in Indian Country Today and is republished here with permission.