One of the biggest sea stars in the world has been devastated by a malady likened to an underwater “zombie apocalypse” and could soon be granted Endangered Species Act protection.

Sunflower sea stars, fast-swimming creatures that can have up to 24 arms and grow to three feet in diameter, have largely vanished from their habitat, which stretches from the western tip of the Aleutian Islands to the waters off Baja California.

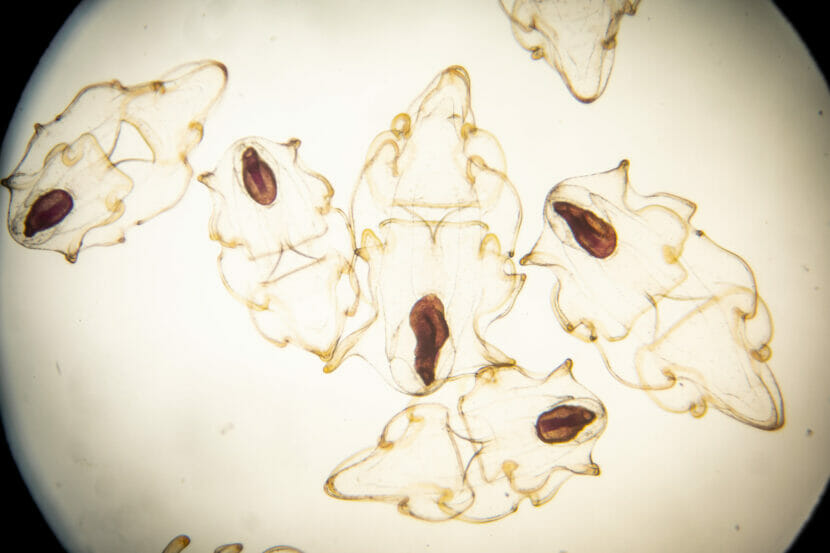

The culprit is sea star wasting syndrome, a body-mangling disease sweeping the North Pacific that scientists say is the biggest known epidemic to hit any wild marine species. Multiple species are affected, but sunflower sea stars have particularly suffered.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is on the verge of a decision on an Endangered Species Act listing sought in a 2021 petition filed by an environmental group, the Center for Biological Diversity. The petition cites an approximately 90% loss of the animals since 2013.

“Sunflower sea stars have been decimated by sea star wasting disease, urgent action is needed to prevent their extinction,” the center’s petition said.

A listing determination should come within a month, said Sadie Wright, a Juneau-based protected species biologist with NOAA Fisheries. If the agency decides to list sunflower sea stars as threatened or endangered, a proposed rule would be published, followed by a final rule a year later, she said.

Endangered Species Act listings allow the federal government to take actions to conserve wild populations facing threats of extinction.

Sea star wasting syndrome has been linked to climate change. The disease “does appear to be exacerbated by warming ocean temperatures, or significant shifts in water temperature,” Wright said by email.

Preserving sunflower sea stars is about more than preventing extinction of a distinctive and colorful sea creature. Their loss is “devastating for the entire kelp forest ecosystem in which they live,” the Center for Biological Diversity’s listing petition said.

“Sunflower sea stars are a keystone species and a top predator in the intertidal zone. In the absence of a healthy population of sea stars, sea urchins can proliferate and devour the kelp forests that provide habitat for many fish and other wildlife. The decline of sunflower sea stars has caused a cascade of harmful changes in the ocean food web,” it said.

While the most severe impacts have been in the southern parts of the range, sunflower sea stars’ disappearance from Alaska waters has been profound. Prince William Sound and Kachemak Bay have been some of the places notably affected, said Brenda Konar, a marine biology professor with the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“I used to see a ton of them while diving in Kachemak and they totally disappeared for a while,” Konar said by email. “They are starting to make a patchy comeback but it is really slow.”

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature in 2021 listed the sunflower sea star as critically endangered. However, the IUCN uses different listing criteria than those used in the Endangered Species Act, Wright said.

Listing holds possible implications for the fishing industry. While the warming-associated wasting disease is the overwhelming threat, an additional threat is bycatch, the unintentional catch in harvests targeting other species. The animals occasionally wind up in the pots, traps and nets used to catch fish, so listing could mean stricter rules preventing that.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game and some Alaska fishing groups, in comments to NOAA Fisheries, argued against listing. Their comments said listing is premature and based on incomplete science and that NOAA Fisheries should consider that there are some signs of recovery emerging in Alaska waters.

Even if the population is nearly wiped out in the southern part of the range, the Department of Fish and Game said in its comment letter, sunflower sea stars could shift their range north. “This possibility changes the lens through which the risk of extinction should be viewed: a population that shifts its distribution can look like an extinction at the local scale, but not at the regional scale or across the range,” the department’s letter said.

Preserving sunflower sea stars could benefit the Alaska fishing industry, however. By keeping urchin populations in check and thus protecting kelp beds, sunflower sea stars benefit the marine ecosystem that produces the fish the commercial industry harvests, scientists say.

A possible benefit of listing would be more attention to the sunflower sea stars’ plight – and that could lead to more support for a pioneering captive-breeding program at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories.

The program, a cooperative effort with The Nature Conservancy, started with 16 adults collected in the wild in 2019. The group is now in its third generation, with over 100 1-year-olds now at the lab, said senior research scientist Jason Hodin, who leads the program.

The Friday Harbor Laboratories operation is far too small to repopulate the Pacific coast with sunflower sea stars, and that is not its mission, Hodin said. “We’re not a sunflower sea star production facility,” he said. “We’re scientists. We’re trying to understand the lifecycle of organisms.”

However, the work at Friday Harbor might lead to new captive-breeding programs, and restocking parts of the range might wind up as part of a recovery plan, he said. “If we can get more of these, and larger-scale ones, there’s a lot more that can be done,” he said.

This story originally appeared in the Alaska Beacon and is republished here with permission.