Before Alaska became a state, there were no formal services for treating people suffering from behavioral disorders or developmental disabilities, and mental illness was treated like a crime.

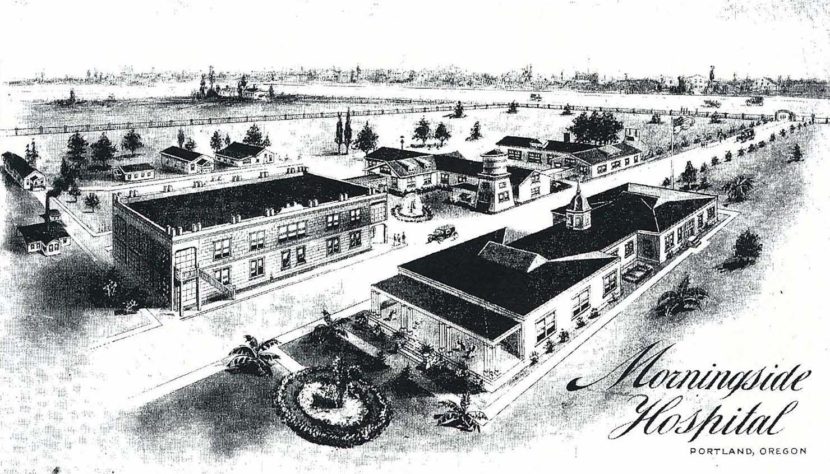

If an Alaskan was convicted of being “really and truly insane,” as it was known at the time, they were sent to an asylum in Portland, Oregon called Morningside Hospital, which opened in 1904 and operated into the ’60s.

At least 3,500 Alaskans went to Morningside, including a lot of Alaska Native people. Many of their families never saw them again. In some cases, similar to the federal government’s dark history of sending Native children to boarding schools, it’s unclear where they’re buried.

Much of what we do know about Morningside is thanks to a small group of volunteers working on The Lost Alaskans: The Morningside Hospital History Project. Among them is retired Alaska Superior Court Judge Niesje Steinkruger.

Steinkruger says some of the criteria for sending someone to Morningside would seem, well, crazy by today’s standards.

Listen:

The following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Niesje Steinkruger: Things like suicidal, head injuries. A lot of head injuries. Drugs, drug addiction, mostly cocaine and heroin. Alcoholism, dementia, epilepsy. And after 1922, about a third of the patients were children, and so those were birth defects, disabilities by names that we now call Down syndrome and hydrocephalic. There were diagnoses of people unable to speak or unable to hear. Senility, or my own personal favorite, “senior exhaustion,” which I understand. Diagnosis of confused, delusional hallucinations. Paranoia. Lots of syphilis that, you know, then had entered the neurological system. And imbecile.

So those are the kind of diagnoses that we saw the most, with people going there. And of course, you’ve got to remember, we didn’t know anything about mental illness during those years. It really wasn’t until the ’50s, when we started getting more treatment ideas from Europe that things started to change.

Casey Grove: My understanding is, of course, back then, the treatment for these kinds of disabilities could be pretty rough, or they used things that we don’t use anymore like electro-shock therapy. And then some folks stayed there their entire lives and then died there. What happened to those folks that died there? Where were they buried? Do we even know?

Niesje Steinkruger: People died at Morningside. Lots of accidents or injuries. Certainly, people died based on treatment. And there was an autopsy room, actually at the hospital. A large number of autopsies were done, and we recently figured out that a lot of those were being, quote, “observed” by medical students from the University of Oregon, but they were probably using the patients as an anatomy class after they died. You know, they didn’t have to get anybody’s permission.

And then they were sent to a mortuary, and they were buried in one of four cemeteries in Portland. Sometimes they’d wait till they had four or five and bury them all in one plot. We’ve found one area where there’s, it’s a ravine that’s gone back to its natural habitat, where there are probably 350 graves. They’re generally unmarked.

But of course, things have happened, like cemeteries have remapped and renumbered their plots. One cemetery, the records were flooded, and we don’t have them. None of the volunteers, we have never been able to find that the state kept a list of what Alaskans were sent to Morningside, no patient list. And so that’s how all of this got started, when we couldn’t find a list.

Casey Grove: Gotcha. Yeah. And I mean, there are similarities here with the boarding schools that a lot of Alaskan Native people were taken away to and never came home from. I guess, also similar to that, there are families here in Alaska that are trying to figure out what happened to their relatives that were sent to Morningside, right?

Niesje Steinkruger: Yes, yes. Many of the stories are, you know, “I remember my grandmother telling me that the federal marshals came and took this baby girl, and we don’t know whatever happened to her.” Or “my mother went to Morningside, and nobody knows what happened.” Or “my uncle got sent to Morningside, and we don’t know whatever happened to him.”

And that’s kind of what really got us started. And our real goal has been to identify who the patients are so that the family can know that, yes, this is where your family member went, and then what happened to them.