In mid-February, 13-year-old Robert Ahmasuk was returning from a hunting trip on skis with his dog Lola near Gunsight Mountain, off the Glenn Highway. Just 50 yards from the parking lot, Lola, a 4-year-old husky mix, started acting anxious and darted off the trail.

That’s when Ahmasuk and his mom heard a yelp.

“I went over there first and I was like, ‘Oh, crap. Lola’s in a trap. Mom, get over here. Help me!’” said Ahmasuk, who lives in Anchorage most of the year.

They attempted to free Lola but knew their time was limited. Despite years of experience with trapping and hunting themselves, they weren’t able to release Lola’s neck from the heavy trap, said Joni Spiess, Ahmasuk’s mom.

“Had we been able to release her from the trap, I’m not sure that she would have survived. I believe her neck was broken by the time we got there,” she said.

A passing snowmachiner eventually helped them get the trap off of Lola’s neck, but at that point, she was already dead.

The loss was devastating to Ahmasuk, but he and his family were surprised to learn that trapping so close to trailheads with a trap that is designed to kill its targets is 100% legal.

“It’s kind of stupid,” Ahmasuk said.

The trap

The trap that killed Lola, a Conibear 330, is a type of body-grip trap designed to kill animals relatively quickly. Some argue that Conibears are more humane because they kill target animals relatively quickly.

Foothold traps, by contrast, are designed to hold an animal alive until the hunter can arrive to either kill the animal or release it. If the trapper doesn’t check foothold traps regularly, the animals might freeze to death.

Brad Christiansen, president of the Southcentral Chapter of the Alaska Trappers Association, said once the animal hits the trigger of a Conibear trap, the 10-inch jaws snap on the animal’s neck.

“That’s usually it for them. There’s not really any struggle or anything like that,” he said.

According to Ahmasuk and Spiess, Lola died less than 5 minutes after the trap snapped on Lola’s neck.

Spiess learned trapping skills from her ex-husband in Nome and said that at one point, she would have been able to remove the trap quickly, but even though she and Ahmasuk were healthy outdoors enthusiasts, they couldn’t remove the trap on their own.

There have been other documented cases of dogs killed in Conibear traps in Alaska, most recently in 2017 in an illegally set trap in Anchorage. But it’s not clear how many dogs have died in Alaska from traps.

There is no central database tracking incidents of pets getting caught in traps. Nicole Schmitt, the head of the Alaska Wildlife Alliance which advocates for more regulations on trapping, said that means that debates about the issues are uniformed. That leads to inertia from those with decision-making power at the Board of Game.

“There’s been about 15 to 20 proposals in the past 10 years to the Board of game, proposing various solutions. They’ve all failed,” she said.

Her group is starting a “Map the Trap” project and is soliciting stories from the public in the hopes of putting together a database to understand where the incidents are occurring.

“The intention behind the project is to understand where these incidents are happening both geographically, and if they’re next to trails, or roads, pull-offs, things like that, and what kinds of traps people are having problems with so that we can try and advise local solutions to that problem,” she said.

So far, they’ve got about 30 reports from the public about trapping incidents since the project began in September, but Lola’s is the only confirmed report of a death.

With limited data that still hasn’t been published, it’s hard to make assumptions about what regulations would help.

The trap that killed Lola was set legally, though recreators and trappers agree that it was set unethically because it was too close to the trailhead. They were within Matanuska-Susitna Borough, where dogs can be off leash if they are in “competent voice control.”

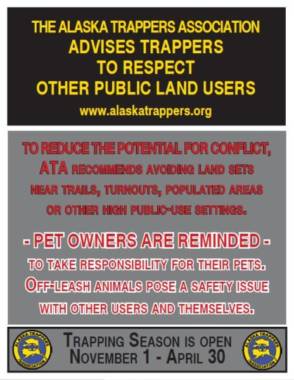

The Alaska Trappers Association recommends not setting traps within 150 feet of high-use areas and trails. Spiess estimated the trap was about 50 feet from the trail.

Ahmasuk’s stepfather posted the details of Lola’s death on Facebook. The post was shared over 800 times and garnered over 600 comments, most of them from recreators calling for more regulation of trapping.

The debate

Most trappers fight vehemently against the idea of more regulations, arguing that the best solution to the rare problem of dog deaths is to remind trappers of their responsibility to act ethically.

“When you buy your trapping license, you’re saying, ‘Hey, I’m going to be responsible.’ And that’s the mentality we need to push in everybody,” said Christiansen.

He was contacted after Lola’s death and put up signs to remind trappers to observe ethics of avoiding high-use areas. He also left a note for the trapper who set the trap that killed Lola asking them to contact the trappers association. So far, he hasn’t heard back.

But Christiansen and other trappers say incidents with pets are rare and deaths are even rarer.

Ahmasuk’s stepdad, Ben Spiess, is preparing regulations to submit to the Board of Game to institute a setback requirement from roadways for large surface Conibear traps. To advocates like Schmitt of the Alaska Wildlife Alliance, that seems sensible.

“I mean, goodness, you can’t shoot a firearm except for defensive life and property off and a quarter-mile from campgrounds. So why can we lay Conibear traps?” she said.

Many trappers argue that regulations like these are a slippery slope.

“It starts with a little regulation here, a little regulation there and a little bit more there. And next thing, you know we’re like California, were trapping is not allowed at all,” said Christiansen of the trappers association.

Christiansen said that for the thousands of trappers who buy a license, extra cash from selling furs from trapping can mean the difference between buying Christmas gifts or not. And he says that the rich traditions of trapping, which contributed to the mapping of the American West by European settlers and continues to be used to manage wildlife populations, is under threat.

Ahmasuk, who grew up learning the trade from his father in Nome, doesn’t want to lose Alaska’s trapping tradition either. But after losing a dog, he thinks that it’s time for more regulations.