There are hundreds of thousands of U.S.-born children living in Mexico and Central American countries who are United States citizens by birth, but can’t prove it, according to the U.S. embassy in Mexico City.

In Mexico alone, there are about 600,000 children who were born in the U.S. About half of them are stuck in a complicated bureaucratic loop. If they tried to enter the U.S., they would be turned back.

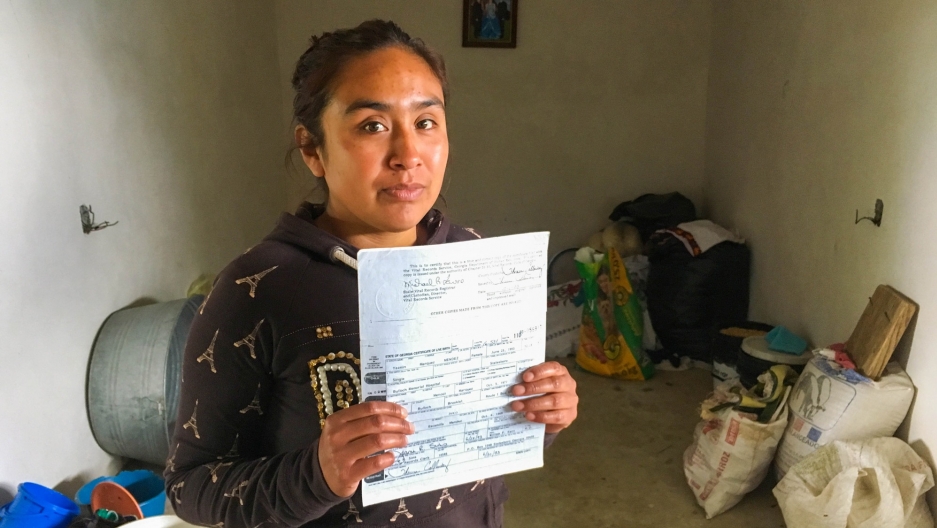

Yazmin Méndez Márquez is among them. She and her mother, Cecilia Márquez, live in the tiny village of Cheranástico, in the state of Michoacán, Mexico. Their living room is empty except for the three plastic chairs and a cardboard box that holds peeping chickens.

Cecilia married at 14 years old, not uncommon for girls in rural Mexico. Soon after, she and her husband moved to the U.S., to rural Georgia. He had a temporary visa to work in agricultural fields.

“It was like a dream,” she says. “We picked onions and sometimes tobacco.”

At 15, Cecilia gave birth to Yazmin. She holds out the birth certificate from the hospital. It shows Yazmin was born in Bullock Memorial Hospital in Statesboro, Georgia, on June 25, 1993.

The U.S. constitution grants anyone born in the U.S. citizenship. But problems for Yazmin started immediately. First, the hospital reversed the order of her last names. In Mexico, a newborn traditionally gets two last names: her father’s and then her mother’s. But in her U.S. documents, Yazmin’s mother’s last name is listed first, as her middle name.

“It never occurred to us that, before returning to Mexico, we needed to get a U.S. passport for Yazmin,” Cecilia says.

A year later, back in Cheranástico, Yazmin’s family tried to enroll her in school. But the school said Yazmin didn’t have the proper documents. So, the family lied and said she was born in Mexico, which allowed her to attend school. But now Yazmin has two different officially documented places of birth: the U.S. and Mexico.

This happens a lot, says Ian Brownlee, who until recently was a consular official with the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City.

“It should be a dying practice to have a false Mexican registration. It takes a long time for everybody to learn that, yeah, it’s okay for little Juancito to be a U.S. citizen and attend school in Mexico,” he says.

Brownlee says the embassy tries to sort out which documents are true and which are false. He says the hardest cases are when the children were born in the U.S. but don’t have a birth certificate, because it was lost or it was a home birth and the parents never got one.

“It is really one of our main priorities here at the moment, documenting these kids as U.S. citizens. Whether they ever go live in the United States is sort of irrelevant. They are U.S. citizens,” he says.

President Donald Trump has a different message, though. As a candidate in 2015, Trump incorrectly claimed that the U.S.-born children of immigrants are not automatically U.S. citizens. And he vowed to end the right to U.S. citizenship in such cases.

Now, amid the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration, many undocumented Mexican families in the U.S. are afraid to ask for official government help to document their children, says Juan Carlos Mendoza Sánchez, who heads a Mexican government agency in Mexico City dedicated to assisting Mexicans abroad.

“People are afraid to ask for help, even from Mexican consulates, because they worry their personal information will be shared and lead to deportation,” Mendoza Sánchez says.

Yazmin, at 24, still lives in rural Mexico and hopes to get a U.S. passport. Mexican officials put her in touch with a pro-bono lawyer 18 months ago to help with the conflicting paperwork. She says the lawyer hasn’t done anything and, on her own, she’s unable to navigate the bureaucracy.

“I want to know the United States. I have one of my sisters over there. I’ve never met her. I want to know her,” she says.

For now, she’s unable to visit the country of her birth.