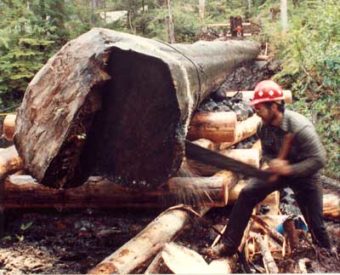

This first real cold snap in several years around Kodiak has got a local tree expert raising an alarm over tree cutting and log splitting. Dennis Symmons, a tree surgeon when he’s not tending to borough business as an assemblyman, says when the local Sitka Spruce tree freezes, it can become dangerous to handle.

“When it turns to plastic and peanut brittle from the cold, and it’s the one thing that even a professional forgets. And I was reminded yesterday, ‘Oh yeah, they’re not trees anymore.’ They’re giant sticks of celery. And when I attach my body to that, 60-feet off the ground, it takes on a whole different persona. Now, throw into the mix of these frozen sticks of celery, rotten cores, cancered bases, and they’re not trees anymore.”

He said the tree is more like “a sweaty stick of dynamite” at that stage, and the scenario could turn ugly quickly when topping or felling a tree.

“So here’s the novice and the professional putting that deep face, like he would into a green tree. Now that person’s coming through the back cut, and already making the first mistake, because all of that weight is getting smaller and smaller concentrated on one spot. The mistake’s realized, too late. Now that all that weight’s shifting on that little teeny stick, if a climber’s off the ground, that little stick is right in his face and he’s got nowhere to go.”

Symmons said that very thing happened to him some years ago when he was working on a tree.

“It looked like a really simple job … about a 90-foot spruce tree on its root wad. I just walked up it. I’m about 14-feet off the ground, with my sharpest, fastest-running chainsaw. And I zipped the top off really quick. And I step back, and without even computing what I just did, you know, leaving the frozen top, I slowly started cutting on that. And theoretically, the elasticity would just peel me to the ground. You now, kind of a show off mood,” he said.

“Well, I got three-quarters through that, seven-eighths through that, and realized – by that time it was too late – that it hadn’t moved. And then it exploded and it launched me upside down, into the air, feet-first. My experienced ground-man logger from Oregon thought I was showing off, doing some kind of stunt.”

He said the outside couple of inches have the most moisture and freeze the hardest. He says the dangers with cutting Sitka Spruce are present even when bucking up logs for firewood.

“(You) go to sink that saw and, ‘Wow, this is really weird, I know I just sharpened this thing, and it seems really dull.’ And about the time I punches through that inch-and-a-half frozen layer and grabs that soft wood, by then a person has already backed off and relaxed. Now the saw’s kicking back, coming at them, and the log’s trailing it,” Symmons said. “I’m trying to draw a real ugly scenario because that’s what it is – it’s an accident waiting to happen.”

And when the next windstorm hits and temperatures plummet to the single digits, what does Symmons recommend homeowners do if a tree in their yard starts to look threatening?

“I think the best thing to do is to get it secured. No matter what the conditions are, get the thing tied down. That’s a big deal. That’s why a tree gets topped, it stops its momentum,” he said. “Step one, if they’re in doubt, tie the thing down.”

Temperatures are expected to hover around the freezing point all week, but even when it thaws, Symmons cautions that the frozen ring around the Sitka Spruce could stay frozen for weeks afterward.