Could Sealaska make more money, pay higher dividends and make better use of its land? Yes, say some shareholders critical of the Southeast regional Native corporation’s management.

Sealaska’s recently released 2014 financial report shows significant improvement.

The corporation, with about 22,000 shareholders, came back from a $50 million-plus loss the previous year. And it streamlined operations, laying off 150 of its 400 employees. Managers say it’s a significant improvement.

But Carlton Smith, a former board of directors member, says it’s not as good as it seems.

“From a shareholder perspective, I think calling 2014 a turnaround year is a bit of a stretch,” he says.

Smith is a commercial real estate business-owner who ran for the board last year as part of an opposition slate.

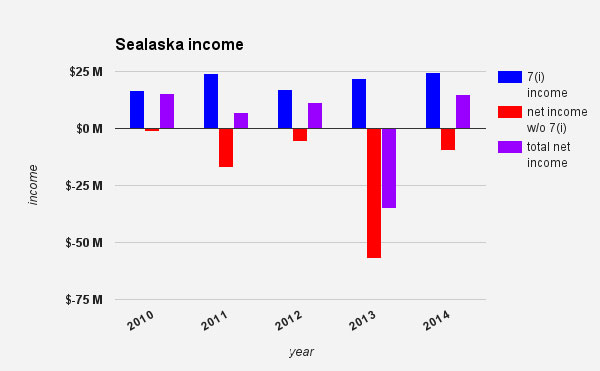

He and others point to the fact that Sealaska’s investments and businesses have lost money for each of the past five years.

Financial reports show a profit for all but 2013. But that’s only when other Native corporations’ natural resource earning – which are shared – get added in.

“The central issue here for at least a decade has been the need to replace timber income,” he says.

Sealaska used to make most of its money from logging. But it cut the best trees on much of its property. It’s getting going this year on new timberland, transferred from the Tongass National Forest by Congressional action.

Smith says no one should expect to reach past profit levels.

“We knew volume was going away. We knew that the markets were changing substantially. So the real issue here is, in a more compressed time frame, trying to replace timber income, which as a single strategy, it’s just not going to happen,” he says.

Sealaska managers know that, so they’re looking for new investments. They’re focusing on natural foods, especially seafood, as well as data analytics.

Smith has his doubts.

“A long-standing truism for a successful business is to do what you know. And if those two areas of new investment are contemplated, in my opinion, we need to have expertise in our existing management team to make sure that we’re going to grow it and grow it right,” he says.

He says he doesn’t think Sealaska has that expertise.

“Sealaska took a big hit last year. They took another hit this year. And nothing in this report demonstrates any changes,” says Brad Fluetsch, an investment advisor who runs a shareholders’ Facebook page critical of management. He’s also one of five independent candidates challenging the same number of incumbents for seats on Sealaska’s board of directors.

He says the corporation has fallen far behind a common gauge of financial success.

“What really concerns me is the dramatic drop in investment earnings. The S&P 500 did almost 14 percent last year and Sealaska did barely 4 [percent],” he says.

Fluetsch says, despite cutting 150 jobs, Sealaska still spends too much on its top personnel.

“They paid almost a million dollars or a little over a million dollars in severance bonuses or termination fees. It just demonstrates this board of directors does not value shareholder money,” he says.

“I see that they’ve cut a lot of staff. Other than that, I don’t see any change,” says Mick Beasley, an artist and former board candidate who’s pushed for term limits and other corporate reforms.

Beasley’s all for resource development. But he says Sealaska could do more than log its lands.

“They could have some housing projects on Sealaska land. I look for boat ramps. I like the idea about agriculture, berry farms,” he says.

The corporation is helping develop berry-picking operations in two villages. But managers say it won’t be a significant enterprise.

“As usual, I think the elephant in the room is this discretionary voting,” he says.

Beasley is among those pushing for an end to that practice. It allows shareholders to turn their ballot decisions over to the board.

That favors incumbents and makes it hard for critics – such as Beasley, Fluetsch and Smith – to win elections.

Sealaska points out that it’s a voluntary practice, and one chosen by at least a quarter of shareholders every year.