When you think of extremely dry conditions, California wildfires probably come to mind. But drought looks very different in a temperate rainforest.

Southeast Alaska has gotten enough precipitation in the last few years to flood some parts of the country. But it’s not nearly enough to sustain a way of life dependent on rain.

In an average year, Metlakatla receives around 110 inches of precipitation. That’s down significantly to 80 or 90 inches a year. Over the summer, when Alaska’s temperatures broke records across the state, Metlakatla was classified as having an extreme drought. More recent fall rains have eased conditions to moderate.

Still, the overall lack of rain means the community is having to navigate a different relationship with water. Parts of Southeast Alaska are still grappling with the effects of the most significant drought in a wet season in over 40 years.

Warmer, wetter conditions are expected in the future. But climate scientists caution: It’s potentially a future with more big swings.

Metlakatla is one of Alaska’s southernmost communities, on the Annette Island Reserve just a short ferry ride from Ketchikan. There’s a common saying: Metlakatla has some of the best-tasting drinking water in the world. In fact, a water bottling company briefly opened up here.

Gavin Hudson, who serves on the Metlakatla Indian Community Tribal Council, said having an abundance of water is an important part of the culture.

“The Tsimshian have always been people of the water,” Hudson said. “People of the salmon.”

Hudson said locals have been noting dry conditions — and the changes they’ve brought — for a while: low salmon returns in streams typically fed and cooled by rain. The blueberry bushes haven’t been as plump or abundant.

And a big difference: Grownups haven’t been able to fall back on a familiar summer joke they would say with a wink.

“The usual thing that you’d hear is, ‘Mom or Dad, can I go swimming on the beach?’ And the usual response, ‘Is there still snow in the mountain?’”

The catch, he said: There used to almost always be snow on top of the mountain all the way through July.

“Now we don’t say that,” Hudson said. “Because even if we get some snow, it’s not deep. It’s just a light dusting … that’s unusual.”

The meaning of drought

Drought isn’t defined by less rain. It’s defined by less precipitation. Snowmelt helps feed Metlakatla’s lakes. It’s like money in the bank. But recently, there’s been more climate variability. Less snow and rain.

Hudson said all this has been making the community feel uneasy.

“I think most of our people who just want to provide for their families … I think those folks have just another thing to worry about,” Hudson said. “High light bills. Oceans that are changing. Forests that are changing.”

The high light bills are because Metlakatla is primarily powered by hydropower, but drought has taken a toll on that, too.

Carl Gaube has worked at Metlakatla Power and Light for more than 30 years.

Generating enough hydroelectricity for a town of 1,500 residents is a big part of his daily life. So much, he sometimes answers to a different name.

“Mr. Power. I have friends out there that call me that when we play basketball,” Gaube said. “’You’re a powerhouse.’”

But Gaube has seen a combination of events unfold that has made providing enough power to his community extremely difficult. With water in short supply, Metlakatla has had to run on diesel, which can make it expensive to turn on the lights.

He said a few decades ago, times were different. Businesses like a local sawmill paid a premium to tap into the microgrid. In years with low precipitation, that helped the electric company buy enough diesel to burn to keep the lights on.

But the sawmill has long since closed. A local fish packing plant recently shut its doors, too. And in the last few years, the Metlakatla Indian Community is having to figure out how to adjust to a new identity: An island surrounded by water and in the middle of a severe drought.

“I just pray that it never happens like this again,” Gaube said.

Can we call it that?

Genelle Winter noticed a dramatic shift after hiking up a mountain to scope out Metlakatla’s main reservoirs.

“When you could see all three of those dams and you could literally walk across that channel … you’re like, this is not a normal condition,” Winter said. “And you probably should never be able to do that.”

You shouldn’t be able to do that, she said, because you would be completely soaked.

Winter’s work previously focused on invasive species. But around 2015, her job title changed. She became Metlakatla’s climate and energy grant coordinator.

She said at first, she struggled with how to describe the unusually dry conditions. It just felt “wrong that you could be in a temperate rainforest and be in a drought.”

Still, Winter said she knew the community needed to scale back its energy use to build its reservoirs back up.

For a time, that’s meant burning diesel for the traditionally hydro community. Metlakatla received funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs for a one-time purchase of bulk fuel, which can be as high as $4 a gallon.

Winter said that’s been a big help restoring the levels of the lakes.

And a phone call from the National Weather Service last year finally gave her a way to put the experience into words.

They told her yes, you are officially in a severe drought, and so are other communities in Southeast Alaska.

“Really helped us to define and really take more ownership of what was going on,” Winter said. “This was something we needed to learn how to deal with now, so that when we met the challenge again in the future, we’d already know how to do it.”

Changing to adapt

But the Metlakatla Indian Community has already taken steps to prepare. Winter has taught students about the drought, even when no one was calling it that. She’s talked to elementary and middle school classes.

And Metlakatla has cut its water use in half since 2016. In part, because the fish packing plant didn’t reopen last summer. Winter also credits the local conservation efforts.

“Trying to teach grown people to change behaviors is really, really hard,” Winter said. “But getting kids excited about changing behaviors is much easier. And if you can get them passionate about it, then they take that message home.”

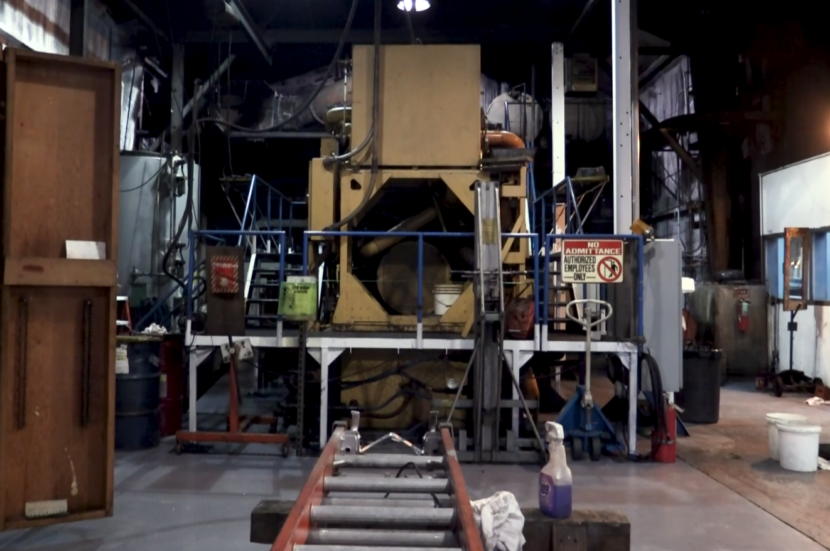

But the community isn’t out of the woods yet. One of its newest diesel generators broke last year, resulting in an emergency declaration.

If another extremely dry spell comes along, the town will be powered by a generator that’s over 30 years old.

As for today, though, the community is back on hydro.

On a final stop, Winter points to a landmark waterfall cascading down the mountain. It’s likely spillover from one of the main reservoirs. During the worst parts of the drought, this waterfall was dry.

The flow should be a happy sight. But Winter said it’s more complicated than that.

“I used to just see it as this beautiful thing. And now, wish we could capture that water somehow,” Winter said.

This system, constructed with the understanding there would always be enough water, was built for a different time.

This story was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.