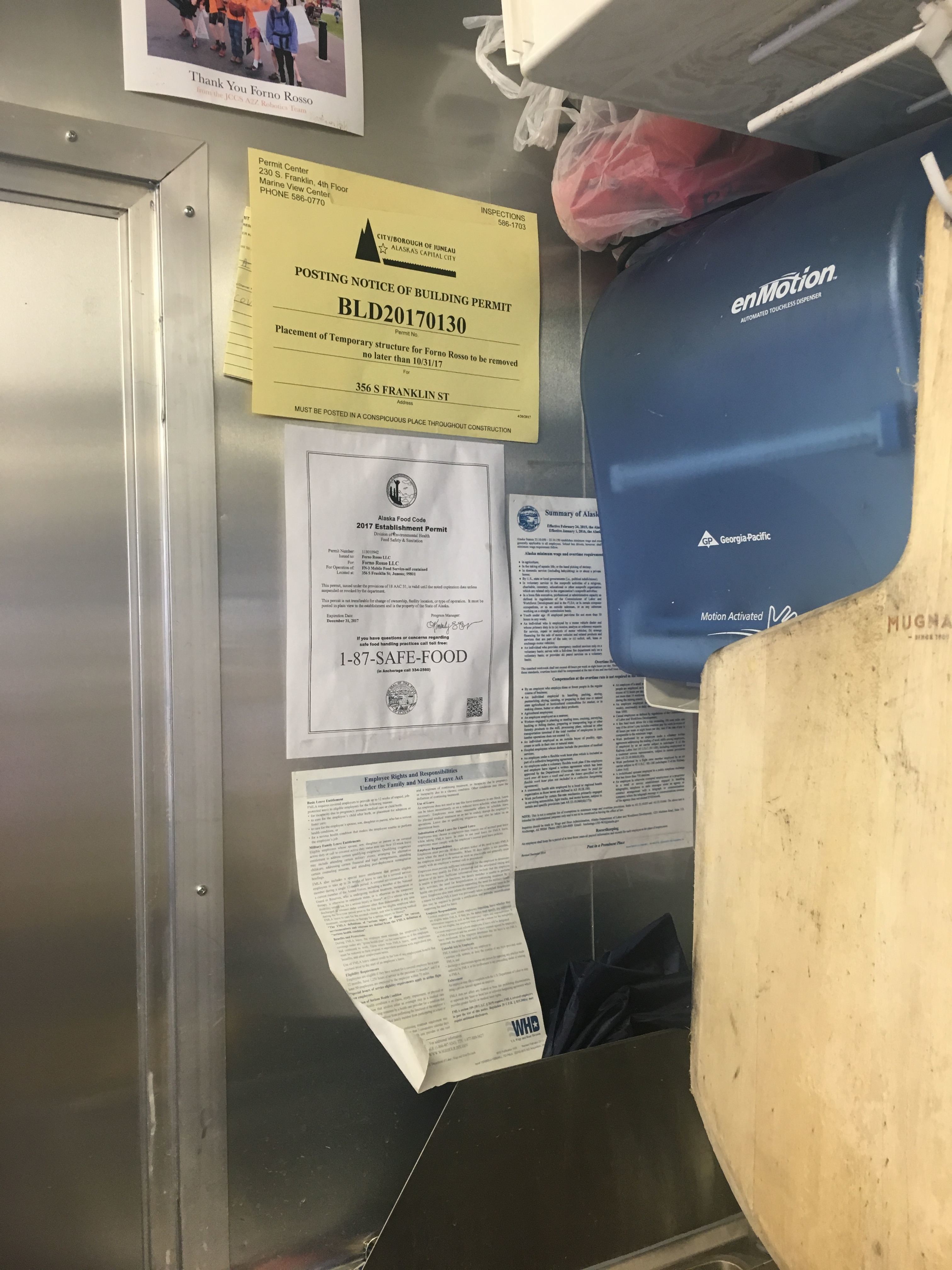

Salmon patties sizzle on a grill at The Salmon Spot, a new addition to Juneau’s many downtown seasonal food stands. Its license hangs just above a box of plastic gloves.

With food inspectors available in town, navigating the permits and getting open for business was a lot of work – but not impossible. The seasonal stands in Juneau are inspected regularly.

In the western Aleutian island of Adak, there are only two full-service restaurants. The federal government considers restaurants high-risk and recommends food safety regulators inspect them four times a year.

But none of the restaurants in Adak have been inspected in over four years.

In 2013, the Aleutian Sports Bar and Grill was cited for rodent droppings and storing food in the kitchen restroom, among other violations. It’s since closed its kitchen.

In Alaska, inspections are creeping further apart. High-risk facilities are inspected on average once every 18 to 24 months. In rural areas, it can be even longer.

Outside of Anchorage, the state’s Food Safety and Sanitation Program is responsible for inspecting restaurants pools, spas, tattoo parlors, food processors and other facilities. The check-ins are intended to protect public health. But after several years of state budget cuts, fewer inspectors are paying fewer visits.

“I would say the number of inspections staff at this point would need to triple or maybe even quadruple for us to be able to get out with any degree of adequacy,” said Kimberly Stryker. She manages the state’s Food Safety and Sanitation Program.

Her inspectors have to triage.

In 2016, 50 percent of high-risk retail food establishments were inspected – up a few points from two years before. Less than one in five low-risk facilities – like coffee shops, bars, grocery stores – were inspected.

Low-risk facilities are only inspected if there are complaints or if inspectors have time.

How frequently Food Safety and Sanitation inspects a facility is based on an assessment that factors in proximity to their offices, the concentration of high-risk facilities, if it is a hub community with access to smaller villages, among other criteria.

“Once you go outside those larger communities, you’re really talking about much more expensive travel, much more difficult travel,” Stryker said.

A round trip Anchorage-to-Adak plane ticket is $1,200, and there’s only one flight a week.

Over the last three years, lawmakers cut over a million dollars from Food Safety and Sanitation’s budget. Two offices closed and a fifth of the staff was cut. And expensive plane tickets to a town with just a handful of restaurants are harder to justify.

“I would say overall it’s resulted in a reduction in our capacity to be able to prevent and respond to illness outbreaks, reports of illness, or reports of lack of sanitation,” Stryker said.

The Federal Food and Drug Administration contracts to inspect facilities that sell food across state lines – usually large processing plants. The state uses these trips to inspect other nearby facilities as well. The state also raised the fees facilities must pay, to make up for lost funds.

“We’re like a puppy dog chasing our tail, that’s just what we do, we’re never caught up,” said Jason Wiard, an environmental health officer based in Juneau. “It gets a little stressful, it gets a little tough.”

Part of the job is being gone for a week or more on trips.

“You might be sleeping in places that would surprise you,” Wiard said. “You could be sleeping on a gym floor, in a clinic cause there’s no lodging, or you might have someone say, ‘You can sleep on my couch.'”

Staff turnover is common in Food Safety and Sanitation because of tough working conditions and budget layoffs. Keeping staff well trained, and investing money in training is a challenge.

In recent weeks two fully-trained inspectors quit. Stryker remembers an employee counting 16 positions that have turned over since November 2014.

Are there consequences?

The Centers for Disease Control estimates 1 in 6 Americans gets sick from a foodborne illness a year.

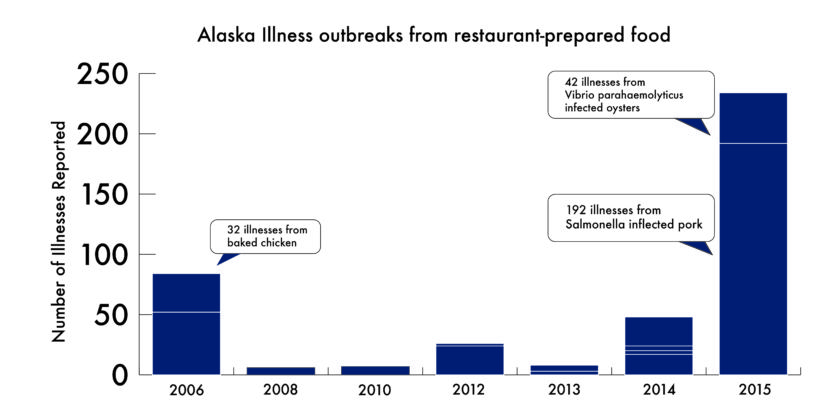

According to the most recent CDC data, 2015 was Alaska’s worst year for foodborne illnesses and hospitalizations since its tracking began in 1998. There were 234 reported illnesses and 31 hospitalizations where the location of preparation was confirmed as restaurants.

“I can certainly speak as an Alaskan first, and as a public servant second, I’m concerned about Alaskans becoming sick with foodborne illness,” Stryker said. “It’s completely preventable and it can absolutely change a person’s life.”

The city manager in Adak said the small town rumor mill keeps restaurants and cooks in-check, but Adak is scheduled to be inspected this fall.

“I’ve been out to rural communities where I’ve been just scared. Like, I know it’s been so long since we’d been out here. You show up and they’re dialed in perfectly,” Wiard said. “I think everybody understands the importance of food safety. Then again, I’ve been to places where you walk in and it’s a disaster.”

There used to be a McDonald’s, a movie theater and a swimming pool in Adak. They’re gone now, just the skeletal, weathered structures are left. A zombie movie was nearly filmed on the island – the perfect apocalyptic-esque set.

“When they don’t see us for a lot of years it’s hard to go in there and say, ‘You’re doing all this stuff wrong.’ And they’re like, ‘Great, where were you for the last 10 years? We’d love to hear this more often, so we’re not out of compliance,'” Wiard said.

In Juneau, sometimes it takes a visit to reassure food safety. In 2011, Wiard shut down Juneau’s downtown soup kitchen, The Glory Hole.

“It was awful, it was egregious, it was the worst thing possible that I could have done,” Wiard said. “They had lots of rodents, and cockroaches and ickies.”

After an overnight cleaning binge, Wiard returned early the next morning to see if the kitchen could reopen for breakfast.

“Just the impact of being able to do that, so folks down at The Glory Hole could have a breakfast that morning, you know, that was some of the sacrifices that I look at – yeah, that was a good thing,” Wiard said.

In rural communities, that level of follow up and education isn’t always possible.

As for the Food Safety and Sanitation Program’s budget for this year, it didn’t lose any more funding.