Courtesy of Rachel Star

When she was 22, Rachel Star Withers uploaded a video to YouTube called “Normal: Living With Schizophrenia.” It starts with her striding across her family’s property in Fort Mill, S.C. She looks across the rolling grounds, unsmiling. Her eyes are narrow and grim.

She sits down in front of a deserted white cottage and starts sharing. “I see monsters. I see myself chopped up and bloody a lot. Sometimes I’ll be walking, and the whole room will just tilt. Like this,” she grasps the camera and jerks the frame crooked. She surfaces a fleeting grin. “Try and imagine walking.”

She becomes serious again. “I’m making this because I don’t want you to feel alone whether you’re struggling with any kind of mental illness or just struggling.”

At the time, 2008, there were very few people who had done anything like this online. “As I got diagnosed [with schizophrenia], I started researching everything. The only stuff I could find was like every horror movie,” she says. “I felt so alone for years.”

She decided that schizophrenia was really not that scary. “I want people to find me and see a real person.” Over the past eight years, she has made 53 videos documenting her journey with schizophrenia and depression and her therapy. And she is not the only one. There are hundreds of videos online of people publicly sharing their experiences with mental illness.

In her early videos, Withers glowers. She tried to give off an aura of toughness befitting the daughter of a Hell’s Angel biker. But there’s also a sense that terror is a deep undercurrent in her life. “All right, let’s go,” she says in the video “Watch If You Forget,” where she documents getting electroconvulsive therapy for depression. Then, in the next few seconds, “I’m about to start the electroshock therapy and, yeah, I’m pretty nervous.”

Things have changed a lot since then. Now, almost all her videos open with Withers flicking her black curls, arms raised with swagger: “Hey, what’s up! I’m Rachel Star!”

That public sharing of mental illness might be making a huge impact on the way our society views these disorders, especially for those of us who are digital natives. Millennials tend to be more comfortable talking about mental health issues, according to a poll released Jan. 14 by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, along with two national suicide prevention foundations.

When it came to seeing a mental health professional, for instance, 48 percent of survey respondents between the ages of 18 and 34 said that it was a sign of strength. About 35 percent of all prior generations felt the same way.

“Our young people are accepting that mental health problems exist, and they want help for it, and they are not looking at these things as something to be ashamed of,” says Anne Marie Albano, a clinical psychologist at Columbia University who is on the board for the ADAA.

She thinks that social media and videos like Withers’ have helped lower stigma around mental illnesses. “Young people take advantage of this,” Albano says. “It gives the opportunity for people to tell their stories and post images. This allows them to feel more hope than prior generations.”

There might be other reasons young people are less concerned about stigma surrounding mental illness. Perhaps as you age, your outlook becomes more pessimistic, says John Naslund, a Ph.D. candidate at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice who studies social media and mental health. He notes that the ADAA poll found that a higher percentage of older adults than young people didn’t believe that something like suicide could be prevented. “Maybe they’ve been through this before and have had people close to them take their own lives.”

He hopes things really are getting better. “It’s very possible. That would be a very exciting change in the way society views mental illness,” Naslund says. But the problem has not been solved. Even if information moves quickly, change is slow. “It’s really important to acknowledge that people who have serious mental disorder still face a lot of stigma,” he says.

When she was younger, Withers struggled with a lot of shame and humiliation over her disorders. “For so many years, I felt like a freak,” she says. Part of that was the religious community she had joined. “Think militant Christian. Like a militaristic type,” she says. When she was 17, she graduated from high school early to attend the former Teen Mania Ministries Honor Academy in Dallas. “I honestly thought that’s what God wanted me to do.”

At the same time, her mental condition was deteriorating. She says her schizophrenia was starting to emerge and transform into something unmanageable. The counselor at Honor Academy diagnosed her with depression and prescribed pills. They didn’t help. Eventually she told them about her hallucinations. “This being a Christian place, they decided I was possessed by demons.”

For three days, Withers fasted. Each morning, she met three of the school’s spiritual advisers, and they spent the day performing an exorcism in a closed room. They read Bible verses, and Withers confessed to everything she could think of that might be construed as a sin — even watching demon-related TV shows like Buffy The Vampire Slayer.

At the end of the crucible, Withers was on the floor, exhausted. “I was young and here are these people who you know, I’m told, are close to God. I was like … OK. It must be right,” she says. “Surprise! It didn’t work. I spent six more months there as an outcast.”

Reducing this kind of stigma is a fundamental reason Withers continues making videos. She wants others to see those struggling with mental disorders with more compassion, and she wants people with a mental diagnosis to see themselves more positively.

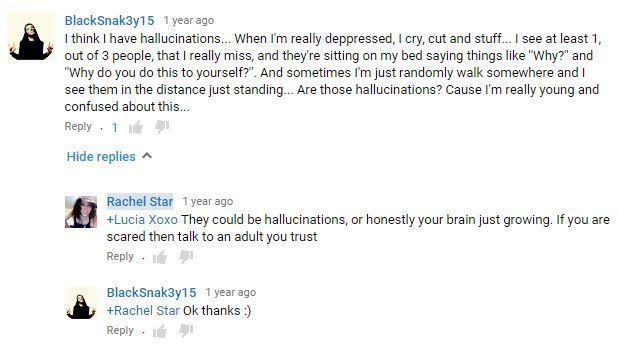

After she posted her first video, Withers says, “People just come out of the woodwork emailing me, messaging me. The friends I’ve had the longest time, even people I’ve never met in real life with schizophrenia and like disorders. We just started talking.” She got invited to mental health forums and to mental health support groups on Facebook.

“Thank you for these videos. They really help me to better understand my sister,” YouTube user Kathryn Hatzenbuhler posted under one video.

These online communities are an important part of Withers’ life now. “Whenever I’m posting on Twitter, I’ll put #schizophrenia and #schizophrenic. I’m hoping to find other people who are having problems,” she says.

Withers ended up making a coloring book for kids with schizophrenia, and she shares ways she has figured out to deal with her visions and voices.

Via webcam, she showed me two askew mirrors in her room that can be angled away from the viewer. “People with mental disorders don’t do well with mirrors. I just start hallucinating,” she says. “It’s real hard putting on makeup, you have to imagine. Having the mirrors at an angle helps.”

In one video, she talks about walking up to one of her hallucinations to touch it, and that alone took away some of the fear. “It’s kind of something to help you get used to your hallucinations, so you know how to respond, because the voices are always horrible. The voices are never like, ‘Oh my God, you look so good today.'”

There’s no hiding her disorder from anybody on Facebook, so people she knew in real life started finding out. It caused her pain at some jobs (“This one girl was like, ‘Oh she’s crazy. I’m not working with her’ “), but it also led some people to talk about their own or their family’s experiences with mental disorder. “They’ll be like, ‘So … I saw your post, Rachel. I had a question.’ ”

Researchers think there’s a potential gold mine of mental health benefits in exchanging messages and encouragement online like this. “Social support is always the No. 1 variable that predicts a better prognosis and better care management of anyone’s illness,” Albano says.

It’s a small leap from there to think that participating in mental health-focused communities on YouTube and Facebook might actually be making people healthier and preventing suicides. “That’s probably absolutely correct,” says Patrick Corrigan, a professor of psychology at the Illinois Institute of Technology. But scientists are only just now beginning to measure the effect social media might have on clinical outcomes. “It’s quite a new area of thinking, online peer-to-peer support for mental illness,” Naslund says.

But there’s an obvious downside to being public on social media about mental health problems. “Say I have a network of friends and I have a breakdown one day. It will spread through social media, maybe in negative ways,” says Michael Lindsey, a professor of social work at New York University. That could be through someone’s real social groups, like at work or school, or it could be anonymous, via Internet trolls. For those already depressed, anxious or paranoid, cruel comments and messages could have a terrible impact.

But in Naslund’s research, he says that problems with online attacks have been extraordinarily rare. “If someone did post a derogatory comment, seemed a little harmful, other people would come to the defense and say, ‘Don’t listen to that,’ ” he says. “[Social media are] way more supportive than we imagined.”

According to Naslund, the benefits seem to vastly outweigh the harms. “That’s clear in the literature,” he says.

And Withers agrees. She doesn’t think that people with mental health problems usually go on social media and spiral out of control even more. “I’m sure it happens somewhere on some area of the Internet,” she says. “But I think usually when I’m feeling depressed and stuff, but then I see someone else thinking of hurting themselves, the opposite kicks in. It’s like, no. You have so much to live for. You’re able to pull yourself out in a way to help someone else.”

When Withers does get trolls, she blocks them. “Anything remotely violent towards me gets blocked,” she says. “Like — I’m not going to respond to that. Don’t call me that word.”

Still, she cautions others to think carefully before coming out to the world about their mental illness. It can be dangerous, she admits. She says she gets phone stalkers and death threats. But she is still glad that she did it. It’s uncomfortable for her to think what might have happened if she never went online about her depression and schizophrenia. “I see myself being a lot more closed off,” she says. “I hope I would have found other people’s videos.”

Withers attributes a lot of her transformation to electroconvulsive therapy. She says it knocked out a lot of her deep depression. And Withers thinks sharing on the Internet has also helped. “It helps me to vocalize it and put it all out there,” she says, and it makes her feel like she is less “broken and sick” when other users empathize with her online.

https://youtu.be/HbnEBfW0UDs

Recently, she posted a video to YouTube called “There Will Be Beautiful Days.” It’s short, reaching just past a minute long. Withers smiles and says she knows things are hard now. Maybe harder than they’ve ever been. But it’s going to be OK. And at some point, you’ll have some good days. Maybe even just one great day, but it’ll be enough. It will make life worth fighting for.

9(MDEwMjQ0ODM1MDEzNDk4MTEzNjU3NTRhYg004))