After an earthquake like the one that struck Cook Inlet on Sunday morning, everyone wants to know how big it was. Scientists use a magnitude scale to describe the size of an earthquake. But getting to that number is a complicated process. And it has some major limitations.

Numbers like 6.4, 7.3, 6.8 — they’re are all magnitude measurements federal and state agencies published following Sunday’s earthquake. It was confusing. What was the right number? State seismologist Michael West says in a way, they were all correct.

“So you got one sensor over here that records some shaking, one sensor in another direction records a whole lot of shaking, a sensor in another direction, eh, not so much and they’re different weighting and location schemes trying to put all those pieces of information together into a single solution,” West said.

The seismic signal from a magnitude-7 earthquake registers across the globe. After an earthquake like Sunday’s, scientists are watching the data as it comes in. Then they actually get on the phone, with the Alaska Earthquake Center, USGS and the Tsunami Warning Center, to figure out the definitive magnitude. West says in about an hour, that process is complete. But he says the agencies want to get initial information out much more quickly.

“We live in an era where in many cases the first indication of an earthquake might actually come from Twitter. People want information and they want to know what’s going on,” West said.

So instead of one final magnitude, agencies release preliminary numbers. West says computers at the Alaska Earthquake Center in Fairbanks, where he works, first pegged the quake at 7.3. USGS sent out a Tweet with a preliminary magnitude of 6.4. When the scientists talked about the data, West says it didn’t take long to agree on the final number of 7.1.

“What people are seeing — they’re getting a glimpse into the inner workings of the system and as more data comes in, as that magnitude and location, and depth are improved and evolve, people are getting to see that,” West said.

West says the Richter scale is hardly in use anymore. But scientists calibrate their other size measurements to essentially mimic that scale so they can maintain a universal standard. They need a way to easily compare the size of earthquakes. The magnitude measurement is far from perfect, West says.

“I think magnitude can work against us sometimes, and the earthquake on Sunday is a good example of this,” West said.

West says the earthquake was a long way from Anchorage — 150 miles — and far underneath the surface of the earth. He fears people will walk away from the experience and think they understand what a magnitude-7 earthquake feels like.

“Had that earthquake occurred at the surface of the earth, close to Anchorage or Homer, the outcome would have been completely different,” West said.

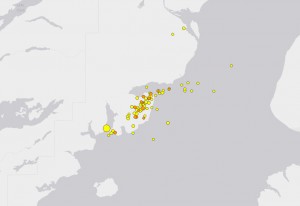

West says the Alaska Earthquake Center has 30 seismic monitors in Anchorage, and they picked up dramatically different amounts of shaking in different neighborhoods. He says that information is much more useful.

“I would love to see people calling, demanding, more information of ‘What was my shaking?’ as opposed to just ‘How big was the earthquake?’”

Because, at the end of the day, he says, how the earth moves in your area is much more important than the number that makes the headlines.

Correction: This story originally said scientists used the Richter scale to describe the size of Cook Inlet earthquake. Instead, they used a different magnitude scale USGS explains here.