A slide that sent rocks crashing onto frozen Mendenhall Lake in late November actually caused a small tsunami.

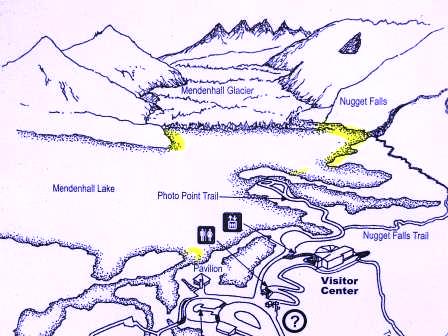

Apparently no one witnessed the rock slide, but Thanksgiving Day hikers on Nugget Falls Trail reported seeing jumbled piles of ice tossed by waves onto the beach. Refrozen ice plates 6 to 8 inches thick can still be seen on the lake.

“The first thing I noticed was that there was broken lake ice on one side and then there was broken lake ice on another side,” said Laurie Craig, a naturalist at Mendenhall Glacier Visitor’s Center.

With no evidence of glacier calving, Craig said trying to figure out what happened was like “geologic forensics.”

A spotting scope trained on Bullard Mountain showed evidence of a rockslide. Tree limbs also were seen in the rubble ice.

“We could clearly see evidence of where this narrow band of rock cascaded down off the mountainside and broke the lake ice that was right up against it,” Craig said. “And then it reverberated under the lake and hit against rock on the other side, which broke there as well.”

How does that happen?

If the rocks had hit water, there would be a big splash and a wave would travel across the lake. That’s simple enough, she thought, but Mendenhall Lake was covered with ice.

Craig posed the question on Friday to Joel Curtis, Warning and Coordination Meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Juneau.

“How does the water pop up on the other side of the lake under the ice? Let’s say the ice is thicker out in the middle. It’s a very, very interesting physics problem and I am asking people who are geekier than I am to look at this,” Curtis said.

One of the scientists he consulted was Dr. Eran Hood at the University of Alaska Southeast, a hydrologist and glaciologist. The two came up with this:

“The wave that was formed propagated right along with the ice, although the wave was dampened because it had to lift the ice. But it still was enough to get across Mendenhall Lake and have water squirt out on the other side.”

Technically, Curtis said, it was like a small tsunami under the ice.

The take away?

Ice is not as rigid as most people think. While the ice on Mendenhall Lake may look stable, it is not, Curtis said. Definitely avoid the face of the glacier, ice caves, creeks, icebergs and the area where the lake flows into Mendenhall River.

“And of course, the freeze/thaw cycle can cause rock slides on any of the steep slopes,” he said. “We all really love the lake and love going out there, but you have to be safe when you do.”

On Jan. 11th, the U.S. Forest Service and Capital City Fire and Rescue will hold ice safety training and demonstrations at the Mendenhall Glacier Visitors Center.